Were you looking for the place the Autozam AZ-1 – a kei car that would only ever be sold in Japan – was born, Basildon in Essex probably wouldn’t be the first place you’d hit upon. Yet tucked away in a nondescript trading estate in the south-east of England stood the industrial unit of Hawtal Whiting, and if you peered inside in early 1991, you’d have seen a tiny mid-engined coupe being subjected to all manner of torture tests.

Bodies-in-white were subjected to bending and torsion tests. Cars were pounded on a four-post road simulator and running prototypes were sneaked into covered trucks for shakedowns at Millbrook Proving Ground. Datasets were pored over, improvements to the suspension implemented and trim choices finalised. The production car might have been born in Essex, but the prototype story goes back a whole lot further.

How much further? 1948 is a good start. That’s when the kei car rule set was initially devised. Designed to stimulate both car post-war car ownership and kick-start Japan’s car industry, the rules specified physical size and engine displacement. For four-stroke engines, that displacement was a maximum of 150cc between 1949 and 1950, 300cc from 1950 to 1951, 360cc from 1951 to 1955 and 550cc from 1976 to 1990, when the Autozam AZ-1 was born.

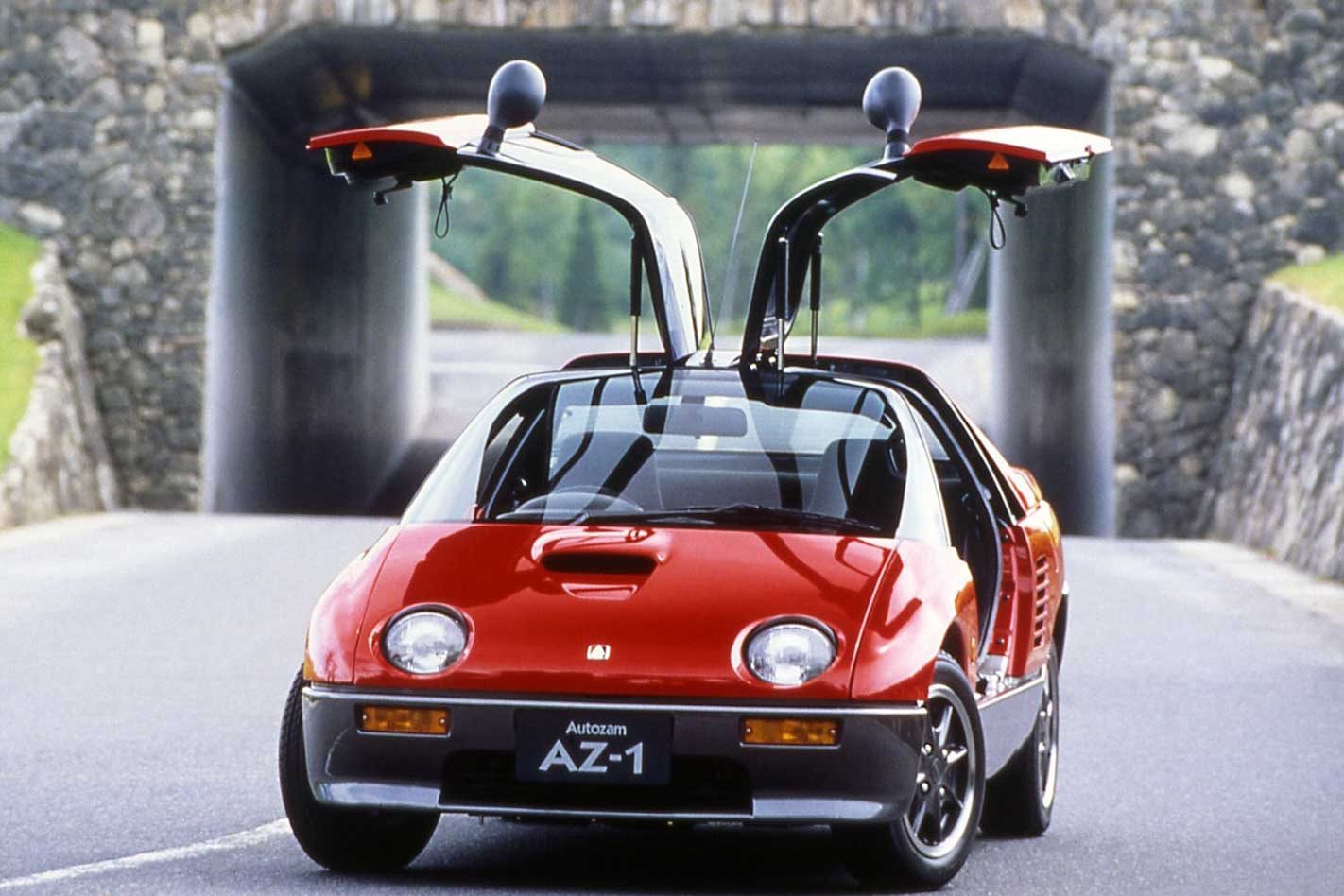

Mazda began working on a kei-car concept in early 1985, creating a one-fifth scale clay model of a design it called the W140. The sharply raked nose left no space even for a tiny 550cc powerplant, which was instead slated to fit behind the driver. Mazda toyed with the idea of a doorless open roadster version but computer simulations showed that body rigidity would be shocking and the baby barchetta plan was dropped. A 1:1 clay model appeared in 1986, and by April of the following year, a running prototype using the engine from a Daihatsu Mira was built. This project was then approved for production feasibility testing, wearing the name AZ-550 Type A.

It probably hasn’t escaped your attention that another compact, mid-engined Japanese sports car with a similar shape had popped up in 1983 as the Toyota SV-3 concept at the Tokyo Auto Show. The very next year, this car would become the production MR2. There’s little doubt that the design of the MR2 influenced the engineering of the smaller W140/AZ-550/AZ-1.

Many web sources state that the Autozam drew its design inspiration from the Suzuki RS/x concepts, but the dates really don’t support this. Suzuki knew nothing of Mazda’s plans for the project until they were approached in 1988 to provide the engine for the vehicle. They agreed, but Mazda was similarly taken by surprise when the Autozam AZ-550 was revealed to the public at the 1989 Tokyo Show, only for Suzuki to be showing their kei car, the Cappuccino. These two models joined the Honda Beat, known as the ABC (Autozam, Beat, Cappuccino) by Japanese journalists.

Three versions of the AZ-550 Concept were revealed. The Type A would eventually morph into the production AZ-1. The type B had a bluffer front end, a less steeply raked windscreen and large, bulbous headlamps. The doors opened conventionally and it featured large rear light clusters. The Type C was the most extreme, drawing its influence from Mazda’s Le Mans-winning 787B. It was shown in blue and white with a bubble canopy, fender mirrors and a wing at the back, wearing the same number 201 on its flanks as the race car.

The purpose of the exercise was to gauge public interest, and more column inches went to the radical miniature race car than the other two combined. Despite this. Mazda came to realise that productionising and selling such a car would present its own unique suite of issues and decided that the Type A concept ought to get the green light. That’s where Basildon came in.

It was inevitable that the AZ-550 would undergo many changes before it became the production AZ-1. Two project leaders came and went before Toshihiko Hirai arrived as Head of Development. The man who oversaw the development of the Mazda MX-5 arrived with a steadier hand on the tiller.

In case you were wondering why the car wore Autozam badges rather than Mazda ones, it was explained by Mazda’s multi-channel sales strategy at the time, where there would be an Autozam kei car line (including the Carol and the Scrum van), the next tier up would be the sporty Eunos cars such as the MX-5 and then the more aspirational Anfini models.

On his first day on the project, Hirai ditched the AZ-550 show car’s pop-up lights, feeling that they were too heavy, costly, gimmicky and out of character for a kei car. He also claimed that the complexity of the motor system would be easily damaged if the front bumper was nudged. “I can’t put that burden on the customer,” said Hirai at the time.

Hirai’s job was made more difficult by the fact that the kei car legislation changed in 1990. Suddenly the maximum engine size had gone up to 660cc and another 10cm of body length was permitted. While it was possible to incorporate the bored-out engine from the Suzuki Alto, Hirai resisted pressure to retain the show car’s vestigial rear seats.

Every centimetre of space was precious and hotly argued over. The spare tyre was originally housed up front, but early in the process it became clear that in the event of an accident it could compromise the firewall and potentially injure passengers. Hirai slotted it behind the seats instead while still finding a way to deliver a little element of recline for the driver’s–seat. While he was undoubtedly a decisive – some might say dictatorial – character, part of Hirai’s genius was being able to lock down the big picture items while allowing specific teams the freedom to tweak the details.

It took three years to bring the AZ-1 to production readiness. The biggest job was changing the show car’s expensive aluminium chassis and replacing it with steel, a move Hirai claimed was necessary on the balance sheet but which he regrets on the basis of weight. The frame was still draped with plastic panels, but the sill width was now a good deal less, making entry and egress easier.

Mazda didn’t build the AZ-1 in-house either. Instead it contracted the services of Kurata Co Ltd. (latterly known as KeyLex), also based in Hiroshima. With a peak theoretical production rate of 1000 vehicles per month, Kurata ticked a lot of boxes. The very first AZ-1 rolled out of the plant on August 8, 1992, the official press launch was September 24 and the very first customer received their car on October 5. Buyers got to choose between two colourways: Siberia Blue paint with two-tone black and blue interior or Classic Red with red and black trim, both being fitted with Venetian Grey lower panels.

The AZ-1 had a major issue though. Mazda couldn’t sell them. The gestation process was so long in productionising the vehicle that by the time it arrived in dealers, the Japanese bubble economy had burst. Two-seat sports coupes with gullwing doors didn’t seem to be at the top of too many shopping lists. A little more expensive than both the Suzuki Cappuccino and the Honda Beat, the AZ-1’s asking price was almost that of an MX-5 and sales came nowhere near Mazda’s target of 800 units per month. Given that this car had been in development, in one stage or another, since 1984, it seems bizarre that it was in production for a little over 12 months. In that period Mazda sold 4392 units, plus 531 being accounted for by the badge-engineered Suzuki Cara sister car. By contrast, Suzuki sold 28,010 Cappuccinos and Honda found customers for 33,600 Beats, easily the weakest product of that particular trio.

In case you were wondering why production ended in June 1993 and you still see 1994 and 1995 model year cars being advertised, that’s because production easily outstripped demand. Unregistered cars were sitting about the dealer network for the following couple of years. In that period Mazda got a little creative, with special edition “optic” models such as the 1993 Mazdaspeed versions which added a raft of dealer-installed options. These featured solid body colours, with a revised bonnet, front air dam and rear spoiler. Firmer suspension was available, strut bars front and rear, a mechanical LSD, and an exotic ceramic and stainless steel exhaust. Perhaps the most sought-after item are the 13-inch alloy wheels that looked a bit ritzier than the standard car’s steelies. Mazda also launched the TYPE L, which was an audiophile version with a subwoofer in the rear.

M2 Incorporated, a Mazda subsidiary car atelier that existed between 1991 and 1995, produced some interesting variations on the AZ-1 theme.The M2 1014 of 1993 was a Safari-style off-road concept, while the 1015A was a rally-inspired concept and the 1015B was another concept with detachable plastic roof panels. The M2 1015 was sold to the public from July 1994, with a revised front end with faired-in fog lamps and the choice of black, white and silver paintwork. A mere 50 units were sold, with M2 being given the option for 50 more. All remaining stock was sold by 1995.

Wheels caught up with the AZ-1 back in April of that year, when the Zega automotive group in Melbourne offered us a group test of one alongside the Honda Beat and Suzuki Cappuccino. Writer Bob Hall was impressed by the drama of the Autozam.

“While the engine is the same as the Cappuccino’s and the statistics for power and torque read the same for both cars, they feel poles apart. Handling of the AZ-1 is somewhat sharper than that of the Cappuccino and in general it’s surprisingly even-tempered. In some situations there’s noticeable low-speed understeer but it goes pretty neutral as you press along,” Hall noted.

“The 720kg AZ-1 was coaxed by Car Graphic to a 0-100km/h time of 9.2s, with 16.6s required to cover the standing-start 400m run. Both times were slightly quicker than those of the lighter Cappuccino,” said Hall.

His verdict went to the Suzuki, as it offered superior accommodation, Hall finding the headroom of the Autozam compromised by the gullwing doors and its raucous character and dynamic focus rendered it more of a specialist proposition than the somewhat friendlier Cappuccino. Yet it’s exactly that focus and sense of specialness that has built the AZ-1’s contemporary status.

Suspension is struts all round with a 25mm stabiliser bar up front and a 20mm item aft. With very low unsprung weight, dampers are right-sized, with 70mm of wheel stroke in bump and 80mm in rebound. The brakes are tiny, discs all round, of radius 91mm up front and 96.5mm at the back. Steering is a quickish 2.2 turns lock-to lock. Weight distribution is claimed to be 44:56 front to rear, which sounds about right.

Hirai knew exactly what he was after in terms of dynamics. “The joy of driving is not just about going fast,” he claimed. “Even when going slowly we wanted to create a car that the driver can feel in complete control of. To keep the idea undiluted, it was important to stay simple and clear. Obviously it would be possible to add more equipment. However, lightness is the basis of athletic performance, and those creature comforts come with a weight penalty. It would just not do. We instead poured all of our energy into the fun of driving,” he said in 1993. Those words rang true back then and make even more sense now.

On Australian roads today, where family sedans can tip the scales at two and a half tonnes, an AZ-1 looks hilariously tiny. It’s the width as much as anything – just 1395mm – which looks so alien, this low-slung car fully 90mm narrower than a behemoth such as a Kia Picanto. Getting into one requires a certain amount of suppleness, and you’ll spot the owner because they’ll be able to slide in quickly and then grab the gullwing door’s pull tag before the door’s action has reached the end of its damped travel. It’s a very slick move. Certainly slicker than flailing for it and having to half-climb out in order to shut yourself in or worse, asking for help.

Being so rare, values are notably punchier than those of a Beat or a Cappuccino. A well-looked after car will typically nudge around $40,000, whereas the equivalent Hondas and Suzukis hover at around half that sum. It’s nothing much to do with provenance or ability, more the fact that gullwing doors have always been cool.

Running an AZ-1 can be a little more involved than you’d think given its fairly proletarian mechanicals. Oil leaks are an issue, especially around the cam housing gaskets and the tiny Hitachi turbo’s oil feed. The gear shifter should feel tight and positive. If it has a flabby action, you’re looking at a new set of shifter bushings. Suspension parts aren’t too hard to get hold of and sway bar bushings can wear. Pattern plastic panels are available, but the exterior parts that are tricky to obtain are windscreens and the finishes around the glass. Getting your hands on decent 155/65/R13 rubber can also be a challenge. For what its worth, Chevy/Daewoo Matiz, Fiat Seicento, Rover 100 and Suzuki Alto/Wagon R all rode on this size tyre.

Rust can be an issue and the plastic body panels can hide a few nasty surprises. Lift carpets, poke around beneath the wheel arches and check door frames. Also check for a cracked dash, as the cluster hood is no longer in stock. Desirable features include the ABS option (check for the module in the front boot) and the foglight/defrost button. Dealer-fit options also included a Momo leather steering wheel, a CD autochanger, CIBIE fog lights and 13-inch aluminium wheels.

There’s a small but very knowledgeable cadre of AZ-1 owners online and they’re an enterprising bunch. They have to be as this is a very specialist car that lacks widespread parts support. As a result,a whole series of home hacks have been developed for it which, for many owners, is exactly part of the appeal. They’re the ones dedicated to keeping this intriguing part of Mazda’s history on the road and we salute them.

Toshihiko Hirai looks back on the AZ-1 project with affection. He’s most proud of the MX-5, as you might expect, referring to it as his eldest son. If the iconic MX-5 is the peak of his life’s work as an engineer, then the Autozam might be thought of as an enjoyable wildcard. “The AZ-1 is my second son: a jerky horse who can’t be trained.”

We recommend

-

Features

Features1992-1995 Autozam AZ-1: Fast Car History Lesson

Miniaturised mid-engined sports car a victim of economics

-

Features

FeaturesKei cars: the coolest Japanese pocket monsters

Quirky, kooky, and oh-so-tiny, Japan’s sub-micro Kei class has spawned some incredibly cool cars – and more than a few bizarre ones too.

-

Features

Features1993: Peak Japanese sports coupe

And why the 25th anniversary of the “golden era’ is significant