Everything from the 1970s and ’80s is in vogue again, from Lamborghini reviving the Countach, to Nissan’s unashamedly retro design for the new Z. It seems the world’s racing fraternity aren’t immune either, with ground-effect designs returning next year.

But instead of simply rehashing old systems, motorsport has found ways to innovate on the early rudimentary aerodynamic thinking of old. Ground effect development ended in Formula 1 in 1982 when the technology was outlawed, and while Group C sportscars picked up the baton for a period, the era of huge underfloor aerodynamics was largely short lived.

For nearly three decades motorsport has almost entirely focused on increasing downforce by utilising over-body aero such as wings and spoilers, and centred around using flat floors not venturi tunnels.

New regs are changing that, with Formula 1 shifting to a ground-effect inspired design for 2022, while Peugeot is returning to top-flight competition at Le Mans without a rear wing on its 9X8 racer. It’s a radical design that could upend how teams approach the iconic endurance race.

The new Hypercar (LMH) rules the 9X8 will compete under regulate a minimum drag coefficient of 1.0, and maximum downforce drag coefficient of 5.2. But beyond that, the ruleset has lifted many of the restrictions around the size and placement of aerodynamic bodywork. While rivals have followed a traditional over-body route, Peugeot’s engineers have found a solution that falls within the pre-set window without traditional wings.

“It is a combination of ground effect and upper rear bodywork that has been worked out in a bit of a different way compared to the old LMP1,” Peugeot Sport Technical Director, Olivier Jansonnie, told Racecar Engineering. “We basically have a combination of the front splitter and rear diffuser. The front of the car is more traditional.”

Modern rules prevented Peugeot using a similar physical barrier to trap the airflow under the 9X8. Instead the French manufacturer’s designers have created an ‘air curtain’.

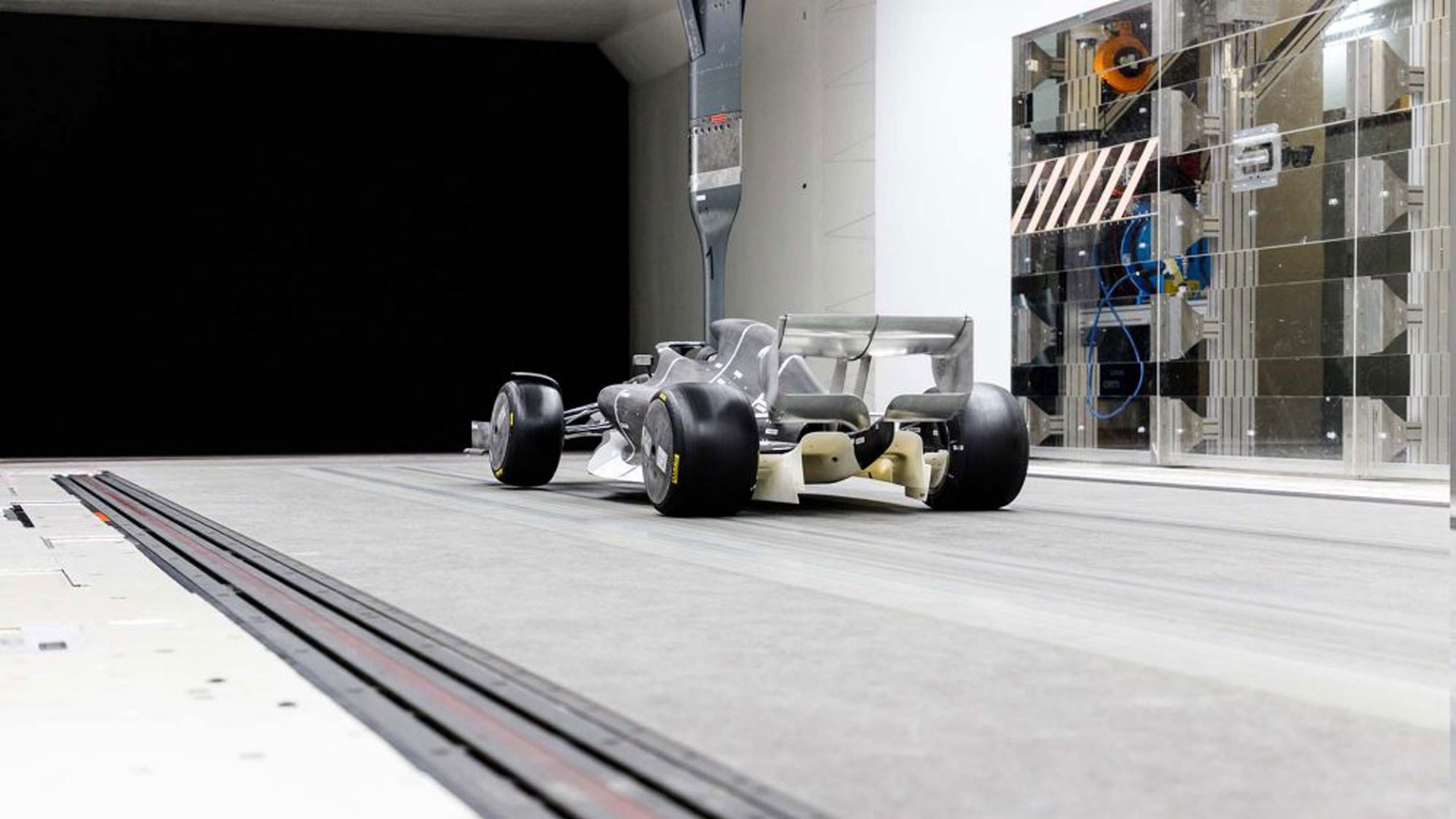

Ground effect works the same in principle as traditional diffusers, generating a low-pressure system to ‘suck’ the car to the ground. Though instead of utilising a flat floor that opens at the rear, it achieves its downforce through the use of sculpted underfloor designs.

As air travels through the tunnels, it is squeezed at the point closest to the ground developing the required pressure. The benefit of a ground-effect design is it is less disturbed by ‘dirty air’ and produces a cleaner aerodynamic wake.

When Lotus first pioneered ground effect with its 78 and 79 racers it utilised ‘skirts’ that sealed the air underneath. Modern rules prevented Peugeot using a similar physical barrier to trap the airflow under the 9X8. Instead the French manufacturer’s designers have created an ‘air curtain’.

The large front intakes channel air in two directions, with most travelling under the car, while some is directed outward halfway down the car’s length with the exterior bodywork then keeping it ‘connected’ to the car. Having already been accelerated by the first half of the underfloor design, this evacuated air forms an aerodynamic barrier for the rear diffuser.

Formula 1’s 2022 regulations undo the mandate for flat floors that was introduced in 1983, allowing teams to incorporate fully shaped venturi tunnels in their floor design. Instead of an ‘air curtain’, F1 teams will use a range of fins underneath the floor to direct airflow and minimise disturbances.

Diffuser design trends dictate that the rear opening begins to kick upward near the rear axle. However, Peugeot’s design begins curving slightly beyond the halfway point of the car’s length – much further forward than a traditional design.

The greatest amount of suction from underfloor aerodynamics is generated at the flat portion as it is closest to the ground, which Peugeot has located smack bang in the middle of the 9X8’s footprint.

The transfer of these advancements to road cars won’t be as immediate or transparent as other racing technologies. By limiting overall downforce in the LMH rules, this means Peugeot’s designers can focus on generating the required levels as efficiently as possible, instead of maximum effectiveness. It’s here that they will see the greatest benefit for road cars.

Car manufacturers are beginning to tap into underfloor aerodynamics more keenly with recent cars like the Porsche GT3 introducing vanes to better manage undertray airflow, while Gordon Murray’s T.50 claims to utilise a ground-effect inspired fan system to aid downforce.

As racing-led understanding grows, so will its adoption on cutting-edge road-going products. A motorsport arms race may not see the next Ferrari sprout large venturi tunnels, but it will help next-gen sports cars stick to the road better without ever larger wings.

The fatal flaw

There are issues with ground effect, particularly on bumpy surfaces. Old-school designs were hugely sensitive to pitch, yaw, and roll, requiring massively stiff suspension. Additionally, if a car bottomed out and the floor touched the ground, it would effectively cut off the tunnels, reducing downforce to zero immediately. You don’t need us to explain what happens when you lose all downforce mid-corner.

What if it doesn’t work as intended?

Peugeot is aware it is taking a gamble with its wingless 9X8 design. Testing is set to begin before year’s end, and months of CFD theory will be put to the test.

“If at any point we find that it is not the right direction, we are sufficiently experienced to change our mind and revise our opinion,” Jansonnie told Autosport. “We have sufficient humility to understand that you need to test to prove that the new ideas are correct.” F1 won’t have that luxury.

Nissan’s attempt

Nissan used a similar concept to that deployed by Peugeot in its GT-R LM in 2015 but were hamstrung by the restrictive LMP1 bodywork regulations. The front-engined car channelled huge amounts of air into a pair of tunnels that then dumped out on top of the rear diffuser. The extremely innovative, but ultimately unsuccessful project showed initial promise – being fastest in a straight line at Le Mans in 2015.

The hidden fans

The iconic McLaren F1 had fan-aided ground effect devices hidden underneath its bodywork. “I had two reflex diffusers, very steep, that the air would not normally follow. It had two 140mm fans, sucking the air out of them and when you switched them on we got 5 per cent downforce and a 2 per cent reduction in drag,” Gordon Murray explained.