Talk of Le Mans and the words “The greatest sports car ever made” and what do you think of? The Porsche 917 has to be there, as does the triumphant Ford GT40. But it’s this car – the Sauber-Mercedes C9 – that holds a special place in sports-car history.

This feature was first published in MOTOR magazine’s May 2009 issue, written by the late Damien Pearce

The C9 is the progeny of the Group C Sportscar partnership between Peter Sauber’s successful Swiss-based Sauber engineering firm and Mercedes-Benz. The program initially saw Mercedes-supplied engines fitted to Swiss-designed cars, run under the Sauber banner. Then in mid-1988, Mercedes-Benz took a greater role in the engineering and established the Silver Arrows factory effort for the 1989 season.

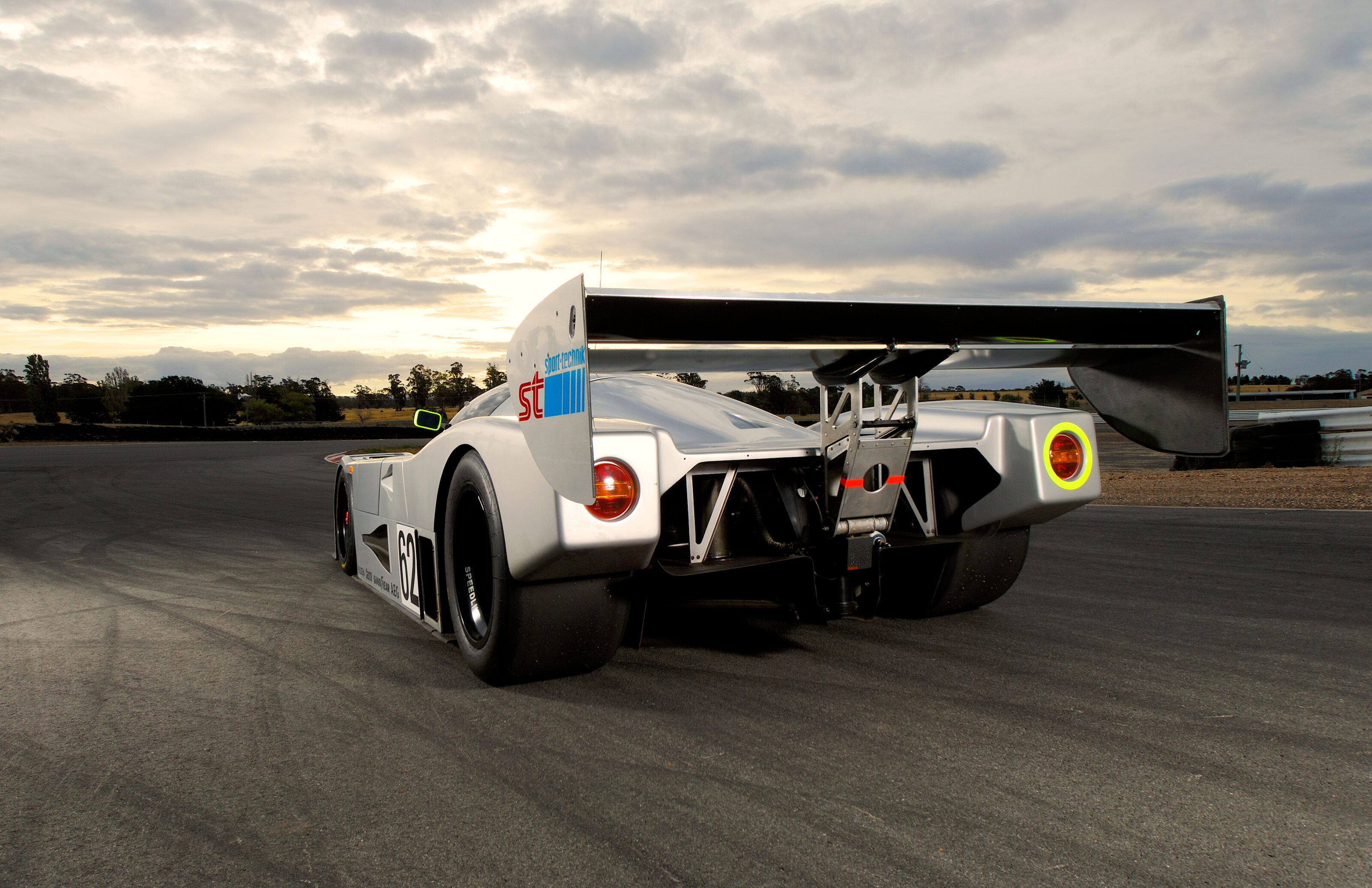

Only six C9s were made, with production beginning in 1987. But sitting in the pitlane at Tasmania’s Symmons Plains Raceway, we have privileged access to the only privately-owned C9 in the world – Chassis Number 5A, one of the final two ‘factory’ cars constructed before the C11 arrived, and the car with greatest provenance. For starters, Number 5A claimed the 1989 World Sportscar (Group C) Championship, with drivers Jochen Mass and Jean-Louis Schlesser winning seven of the eight races (five in 5A) and scoring 155 out of a possible 160 points.

The C9 finished first and second at Le Mans in 1989, but it’s Chassis Number 5A that is a genuine icon. Following a season of world domination, it was mothballed and only saw the light of day again in 2008 when purchased by Aussie collector Rob Sherrard. And here’s the thing: Rob doesn’t like mothballs, hence why I’m loitering nervously in the pit garage, circling the only active C9 in the world.

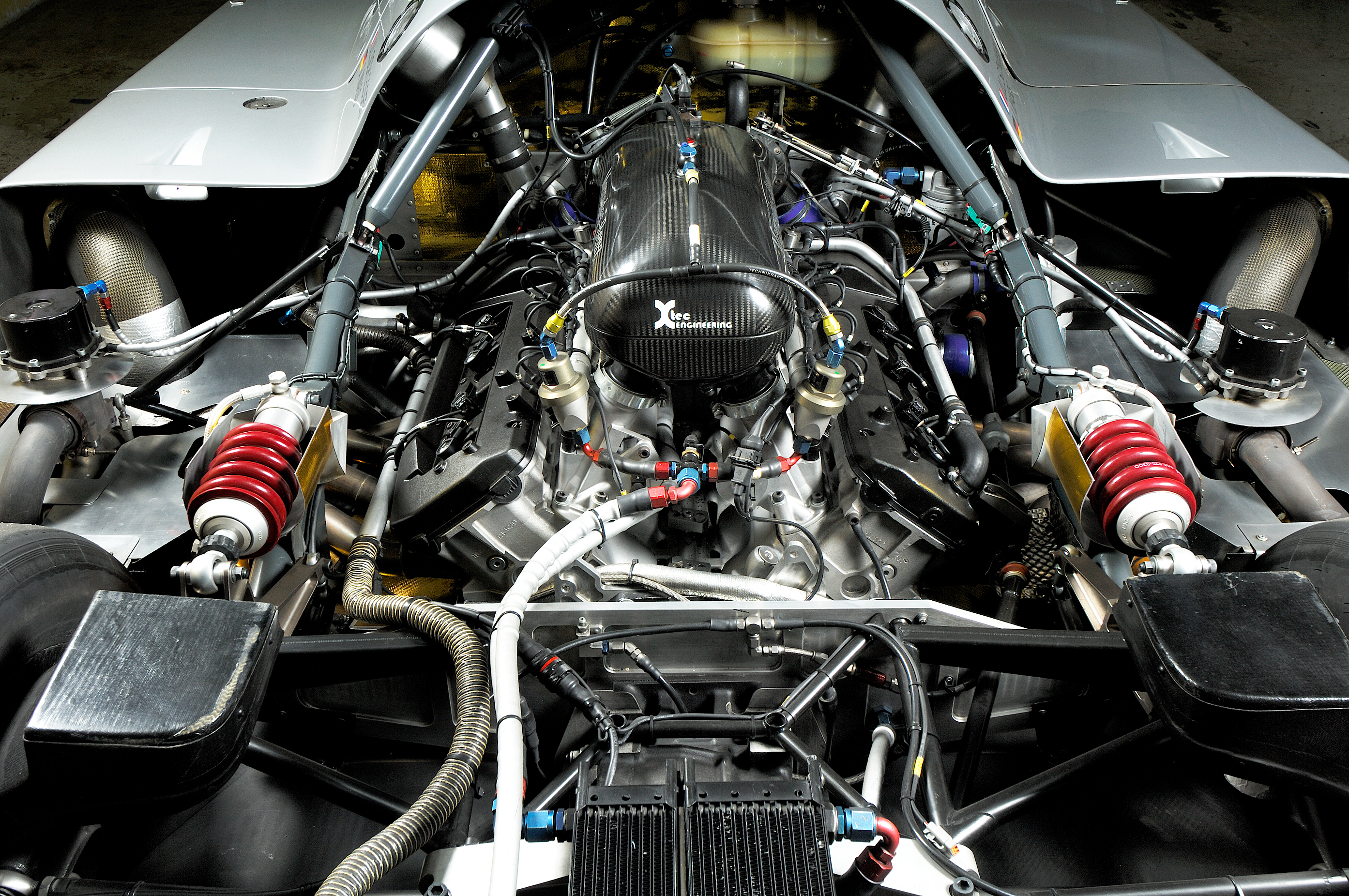

Powered by a 5.0-litre twin-turbocharged and intercooled, all-aluminium V8, the C9 produces 686kW on 0.75 bar boost, although it can be dialled up to 1.1bar if you don’t mind rebuilding the engine every few miles. It’s a car that likes nines, with around 900Nm and 900kg, and a daunting power-to-weight figure of 758kW per tonne.

“Hard acceleration from second through to fourth-gear is mind-blowing. Clichés apply but this is the first time I can’t exhale normally.”

Beneath the carbonfibre bodywork lies double-wishbone suspension with titanium springs, remote Ohlins dampers, hefty 300mm Brembos and four-piston calipers all round. The gearbox sits behind the V8, its five huge dog-gears requiring a firm hand. The twin KKK turbos are tucked low on either side of the engine, just visible through each exhaust aperture, while up front are the radiator and braking reservoirs.

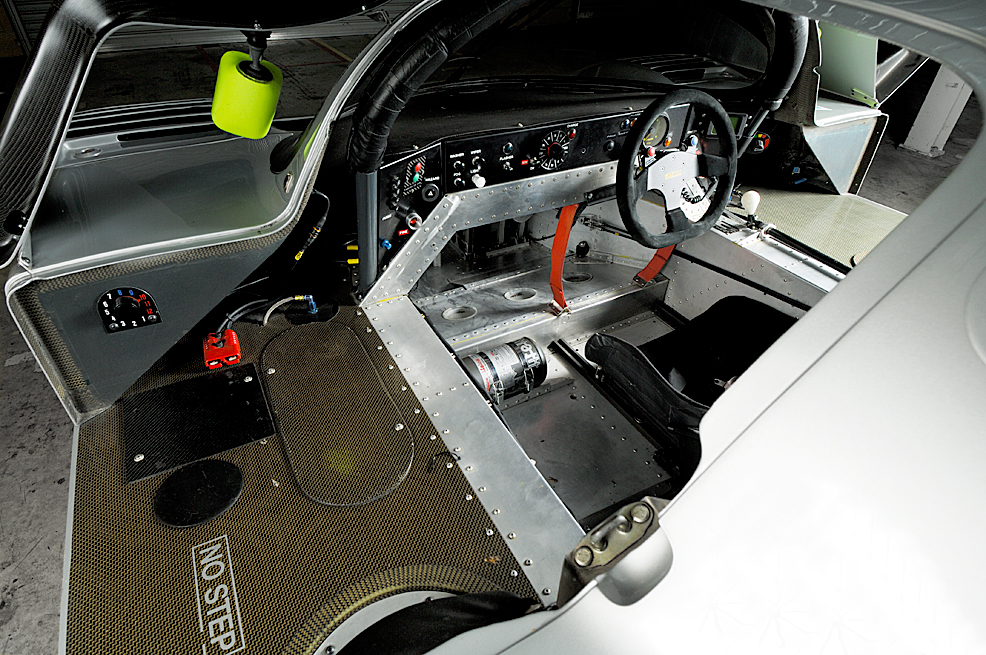

The whole lot is attached to the aluminium tub containing the early Bosch Motronic facia (now hiding a Motec), with a simple aluminium dash dominated by a tacho that gets nervous at seven grand and shows redline at 7200rpm.

As I wait for my driver, just the thought of what this amazing combination can do has me mentally preparing for motion sickness due to the imminent terror prior to experiencing the honour of piloting a C9. Drivers of C9-05A are few – Mass and Schlesser, then Rob Sherrard and Wayne Park in an Historic Group C campaign last year in Europe – so we’ll sample the Mega-Merc around the Tasmanian circuit with an experienced pilot: Sherrard himself.

The C9 looks like a single-seater, but believe it or not, the rules required passenger harness points to be fitted along with provision for a seat. That’s good news as I gracefully fold myself into the cockpit alongside Rob, who’s happy to provide me with a full appreciation of the car’s astounding capabilities.

With the ignition on, oil pumps primed and my eyes glazed, Rob hits the starter and the V8 explodes into life. This is crazy-loud, like no other circuit car I’ve heard, and we’re merely rolling onto the track on already-warm slicks and brakes.

Then everything changes. Forever.

My lungs feel strange. My vision’s blurred. I’m totally unprepared. Hard acceleration from second through to fourth-gear is mind-blowing. Clichés apply but this is the first time I can’t exhale normally. Full throttle dictates that I must consciously control my breathing, all the while accompanied by a soundtrack heralding Armageddon.

Global financial crisis? Least of my problems. Plummeting superannuation balance? Don’t care − more likely my heart will fail within minutes, and it’s not just the 686kW to blame, for this car has a full body-tossing, g-force pushing, ground-effect aero package.

As Rob snatches gears exiting the track’s hairpin, we obliterate the laws of physics, pushing from near-walking pace to just shy of 270 through the long right-hand sweeper, pulling a very noticeable 1.5g mid-corner. The only ‘worries in the world’ are reserved for me because the C9 has none.

It feels glued, and the faster it goes, the tighter it sticks. It’s a strange, yet exhilarating experience to encounter genuine aero for the first time. We’re bouncing all over the track through the rough sweeper, but the downforce of around 2000kg, combined with the inherent mechanical grip, sees Rob blast straight through – busy at the wheel, yet unaffected in terms of pace.

Sure we’re at 270 km/h, but judging by the seat of my pants, we’re not at, or anywhere near, the limit of the chassis, regardless of threatening undulations. Maybe it’s different from the driver’s side, but the C9 gives the impression of a carnivore able to dis-member anything it encounters. It contains violence untapped, but uses it for good instead of evil when pounding a racetrack into submission.

According to Ben Hanson, the man in charge of Rob’s collection and holding a wealth of European racing and engineering experience, the C9 delivers on multiple fronts. It’s obviously fast, and the low-revving Merc V8 is tough and reliable, but it’s the traction that makes it special.

“The only real issue this car ever had was it used more rear tyre than anyone else because it just lays so much traction down,” he explains.

“When we first got it, the guys thought it was down on boost pressure because they just couldn’t get it to wheelspin out of corners. They were trying to find the limits, but it just wouldn’t do it. We had wastegates off, we checked pressures, all was fine, and over time we just worked out as it accelerated away from the Nissans and Jags it simply put the traction down. It’s just very well designed.”

Everything, right down to the braking, is at an unprecedented level. The 300mm Brembos may not seem all that large by even today’s performance road-car standards, but the set-up allows super-deep corner entry at maximum pace before you stomp on the pedal, generating more than 1.4g – the C9 never locking a wheel thanks to the aerodynamics applying huge force on its Dunlops.

My brain needs reprogramming to accept just how high entry speed should be to get the best result. It’s counter-intuitive, though I don’t have time to ponder it, as on each exit we’re being brutalised by 900Nm as Rob again rips through the gears, changing at 7000rpm, pulverising my innards. It defys belief that a car can be so sorted yet so brutal, so dominant yet so composed, and generate so much traction that wheelspin is simply unheard of.

We’ve only been at it for six laps, but I’m shot. My muscles are fatigued from the NASA-like forces, my head’s fuzzy from having to consciously control my breathing while processing images of potential doom, and I’m squashing Rob around left-handers, no longer able to prevent the lateral g-forces from dictating my movements.

I knew this would be the fastest car I’ve ever been in − the record books confirm it − but it’s colossal in every respect. I’m simply unprepared for how devastating it is. And now, after several Bex and a lie-down, it’s time for a steer. I receive instructions and overt threats from a frowning Ben Hanson, but I’m suited up, buckled in, savouring my big moment.

It all ends in tears. After Christmas rolled off the back off a truck and into the pitlane, the chance to unwrap my present was thwarted by my big feet. It’s like Santa has just bypassed my place because my legs are longer than a clearly selfish Sauber engineer allowed for.

In simple terms, I don’t fit in the C9 very well, to the extent that I can’t really drive it, as my feet don’t clear the tub above the pedals and no matter what, I just cannot hit the accelerator without clipping the brake. It’s a long story, literally, as for three hours I try a combo of home-surgery and driving in socks, but basic geometry leads to sulking, Ben to laugh with relief, and Rob to suggest perhaps I’m chicken. I wish I was, for even the heftiest chook is at least short. I’ve the opportunity of a lifetime, and deflated, I’m handing it back.

But despite being unable to lap it properly, and despite having to call Editor Amac to inform him I’m fine but the car’s abnormal, it’s a truly unforgettable day with a truly astounding car.

It generates hysteria with the punters in Europe and is seconds-per-lap faster than the competition, including those built later, near, or on the 1994 Historic Group C category cut-off. The 1988 Sauber-Mercedes C9, Chassis Number 5A, is not only the best car to grace a track in Australia, it’s up there with the greatest on the planet.