If Neville Crichton’s life was a movie, critics would slate it as overblown, absurd, unrealistic and a load of bollocks.

First published in the May 2016 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

“Born in a far-away land called New Zealand to a penniless farmer, he builds a series of multi-million-dollar car businesses around the world, loses all his wealth overnight and grows it again, while simultaneously becoming a champion race driver, bedding babes and skippering race boats at the highest level, including two wins in the Sydney to Hobart, all despite contracting throat cancer, surviving with a hole in his throat instead of a voice box and thus risking death if he falls over the side of one of the super-yachts he’s designed.”

Many believe he could also play the bad guy in the film, with a ruthless, winner-take-all persona. This is not his life story – we simply don’t have room for that – but even the highlights of what sounds like a life lived thrice over beggar belief.

***

SOMETIMES one story, a single moment, can tell you everything about a bloke, and can cause his life to pivot wildly. In Crichton’s case, it’s a tale of bacon versus sausages.

“When the police came around the last time I had four or five cars at home, and they were pretty strict about it, too,” he grumbles. “I’d do the sanding down, get them painted, sell them off. I was just a backyard car dealer, but I thought I’d better get into the business.”

“I remember it was a Holden Monaro. I borrowed some money and within six months we were the biggest used car dealer in Auckland. The business just took off; it was easy, and I loved it. I just absolutely love selling cars.”

By 29, Crichton had made his first fortune and decided to sell up, buy a yacht and go sailing the Pacific, indefinitely. But about 10 months later, in 1975, that significant moment arrived.

“These guys were talking about all these deals and decisions and the only decision I had to make today was whether to have bacon and eggs or sausages and eggs, and I was struggling with that. I had to get off that boat. They’re doing deals and I’m this fucking dumb yachtie, doing nothing.”

Crichton went straight to the airport and bought a ticket home where, not for the last time in his life, luck stepped in.

“Everyone said, ‘Forget Mazda, you’d rather have herpes than Mazda’, but I felt it gave me an opportunity to get into the car business. Within three months we were doing 300 cars a month and we were away. My timing couldn’t have been better. The little 323 came out, it was a good car and Mazda went through the roof.”

***

LUCK, it seemed, was on Crichton’s payroll, but then his fortunes changed, drastically, in 1979. He was diagnosed with throat cancer, despite being a non-smoker. Doctors speculated that a kick in the throat while playing rugby as a kid – which left him with a Darren Lockyer-like voice and the life-long nickname of Croaky – was likely to blame.

“It was bloody difficult; your brain’s wanting to express things, but you can’t say a word,” he says, his rattling yet booming voice coming out of a 50c-sized valve in his throat that he has to hold closed, blocking off the airflow and vibrating the muscles in his neck, to talk.

Crichton was the first person in the world to have this then experimental procedure, after tracking down a doctor in Indianapolis who was struggling to find willing guinea-pigs.

“It was pretty agricultural, and still is, but it works,” he shrugs.

“After one of the last big operations, I got out of hospital, went on the boat and did a trans-Pacific yacht race. Which wasn’t the smartest thing I could have done. But that’s the way I handled it; I never, ever accepted there was an issue.”

Dogged, damned determination got him through again when, at the end of 1981, he was told he had three months to live, an announcement he says changed his life.

“I just didn’t accept that I had cancer; the hole in my neck pissed me off a bit because I [used to] love swimming, and water skiing and surfing, but I didn’t slow up on the yachting. If I fell in the water I was gone, I knew that, but I still did some stupid bloomin’ things on boats…”

This included capsizing a maxi-yacht, in the middle of the night, which should have killed him much quicker than cancer.

“I didn’t think about [dying], I was just more worried about the boat and the crew; it wasn’t good,” he recalls.

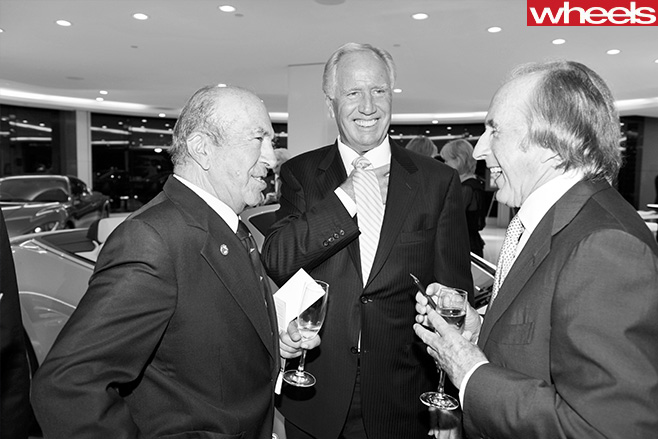

In Australia, Crichton raced for the JPS BMW team – infamously neglecting to tell the cigarette-sponsored team about his throat cancer until after signing the deal – the HDT and Dick Johnson, and partnered legends like Jim Richards, all while running a huge business during the week, and still racing yachts.

“I remember we had a [TV] hook-up from the America’s Cup to the car at Bathurst one year; we had a three-way conversation with [Kookaburra skipper] Iain Murray on the Cup boat, Dick Johnson and myself, while driving around Bathurst.

“I love cars. I love driving fast. I was always convinced that if my teammate could do a time, I could do it. Mind you, the first time I drove around Bathurst I was so slow you could have taken my time with a sun dial. But Jim Richards was fantastic; he would tell me where I was going wrong, and I was a very good copier.”

“I just wanted to build a boat and couldn’t get anyone excited about it, so I set up my own yard, just to do my boat, and then someone else was interested and suddenly I’m in the boat business. I basically started the super-yacht industry in New Zealand,” he says, without a trace of modesty.

But how does anyone do all this, all at the same time? Does he not sleep? “Oh no, I’ve got to have sleep, at least five hours,” he laughs. “But there’s no such thing as an eight-hour day.”

“You do get spotted in the street; I quite enjoyed that, actually,” he grins.

***

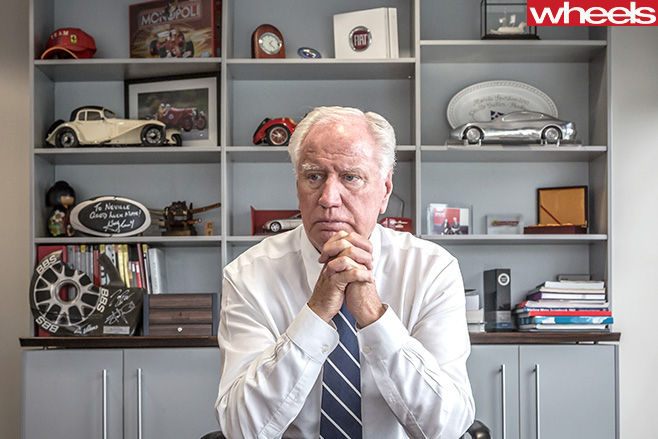

CRICHTON is not a man who minces words; he tends to barbecue them, particularly when it comes to people he feels have slighted him in business, or journalists, many of whom he treats with raging contempt.

He later sued some of the country’s wealthiest coal barons and two high-profile stockbrokers for misleading and deceptive conduct over millions of dollars secretly funnelled to the Obeid family.

Partly it seems to be a fear of being sued that makes it hard to get anyone to comment about him on the record, but as one industry insider put it, “there’d be as many views about him as there are people who’ve met him”. Others speak of his brutality with staff, his ruthless business practices and high turnover of female partners, describing a man of win-at-all-costs intensity.

“Kia were so smart they halved their business when they took it off me,” he thunders. “It was making in excess of $40 million a year; they turned it around from 26,000 cars a year to 15,000 cars and lost $100m in the first 18 months. I couldn’t believe it – they were all, ‘Crichton’s making too much money, we’d better be greedy and take it back’.

“I remember saying it’s disappointing because the business is bulletproof, even the Koreans can’t fuck it up. But they did, they found a way.”

“When we first took the franchise over, I took an F430 home and I thought, ‘This must be the biggest bucket of shit I’ve ever driven in my life’,” he recalls. “I couldn’t believe how anyone would buy one. It couldn’t get up my driveway. I thought, ‘How could anyone pay $400,000 for this?’ I’ve got to say the cars have got immensely better, but the early ones were just shocking. I never took another one home, ever, but I sold lots of them.”

Making too much money may have cost him at times, but ask Crichton if he’s ever had any failures and he goes silent for quite some time, trying to think of one.

“I remember just after that, Audi advised me I’d got the franchise for Australia and I was struggling to find the money to fly to Germany to sign the contract. But we borrowed the money to set it up, and sold that to Inchcape for $25 million in goodwill, and that got me going again.”

Crichton is 70 now and lives in Point Piper right next door to ‘Aussie’ John Symonds’ mega-mansion, but he reckons if a burglar broke into his house “they’d look around and say, ‘you need a bit of help, here’s some money’.”

He doesn’t take holidays, nor can he seriously consider completely retiring because he’d be “bored stiff”.

“I’ve always said when I don’t want to go and sell a car on the floor any more I should get out of it, and it’s getting close to that time now,” he says. Five minutes later he’s downstairs, schmoozing a former Ferrari customer, his patter as smooth as his voice is rough, his eyes still twinkling with little dollar signs.

You couldn’t make him up.

Ask a range of people what they think of Neville Crichton and you’ll hear the same words a lot: “not on the record”, “competitive”, “tough” and “bastard”.

There are rumours of some friction between Crichton and Ferrari over its decision to take the brand back in-house locally, but Herbert Appleroth, CEO of the local arm, barely has an unkind word to say about him.

“I have enormous respect for Neville as a businessmen as well as a sportsman,” Appleroth says. “What he has been able to achieve in business as he also has done in sport is a credit to his determination and competitive spirit. However, on the flip side, like in sport, Neville likes to win and not give an inch.”

Compatriot and former teammate Jim Richards says he’s never had a cross word with Neville, but then he’s never been in business with him. He rates him as a driver, though.

“It’s hard to know how good he could have been if he’d done it full-time, but he drove very well, better than a lot of other guys, and he’s beaten me in races in New Zealand,” Richo says. “There were a few people doing it as a part-time thing back then, but he was better than that, he was like a professional. I think he could have been bloody good.

“He was very successful in business. When he did something he wanted to do it to the best of his ability, but with racing he couldn’t because he had to work. If the phone rang he’d have to answer it, even at Bathurst.”