The Aussie-built Godzillas were the world’s best Group A GT-Rs.

This article was first published in MOTOR March 2009

If that sounds like a parochial, throwaway line, consider this from Doctor Godzilla himself, Fred Gibson. “We went to take our car to Mt Fuji one year to race in the Fuji 1000. The promoters invited us over; all expenses paid. I thought that sounded pretty trick, but I got a phone call from the boss of Nismo, Mr Kakimoto.”

“‘Why is that so, Kakimoto-san?’”

“‘Ah, Gibson-san, your cars too quick. We don’t want to race our cars against yours.’” Nismo, you see, made a killing from Japanese GT-R privateers and didn’t want the business to, quite literally, head south.

“They supplied race-ready engines to [privateers] with 500bhp [373kW]; ours had 625bhp [466kW],” Gibson continues. “We would have blown their socks off them. He was smart.” Smart’s one word for it, alright. Nismo-sourced GT-R water pumps were $9000 a pop. Hence Gibson Motor Sport developed as many components as possible locally during its R32’s program.

Richards also used the GT-R at Oran Park’s finale to wrap up the ’90 title. In 27 Group A touring car appearances, the GT-R won 16 times.

At its peak, in 1991 – before CAMS saddled the GT-Rs with a higher minimum weight and restricted boost – it was virtually unbeatable: nine wins at 11 events.

Dick Johnson’s Sierras ruled the roost in 1988-89, even sneaking in a sortee to Silverstone, snaring pole against Britain’s best. A fuel pump seal failed late in the 500km race, depriving Dick and John Bowe of victory while leading, but the message from the famed Tourist Trophy was clear: Aussie Group A cars were rockets.

Back home, Johnson’s ferocious red machines treated the ATCC like it was a playground full of kids to bully. Nissan had been one of the bullied. Its angular Skyline turbo sixes weren’t complete duds, but they were vulnerable to attack. And then someone at Nissan HQ looked closely at the Group A rules and decided that the Skyline’s problem was nothing to do with power.

The all-wheel-drive Atessa ET-S, essentially the system developed for the Porsche 959, was adopted and built under licence by Nissan in Japan. Gibson and Nissan Australia had a hand in defining the roadcar’s specifications, 100 of which were complied for our market.

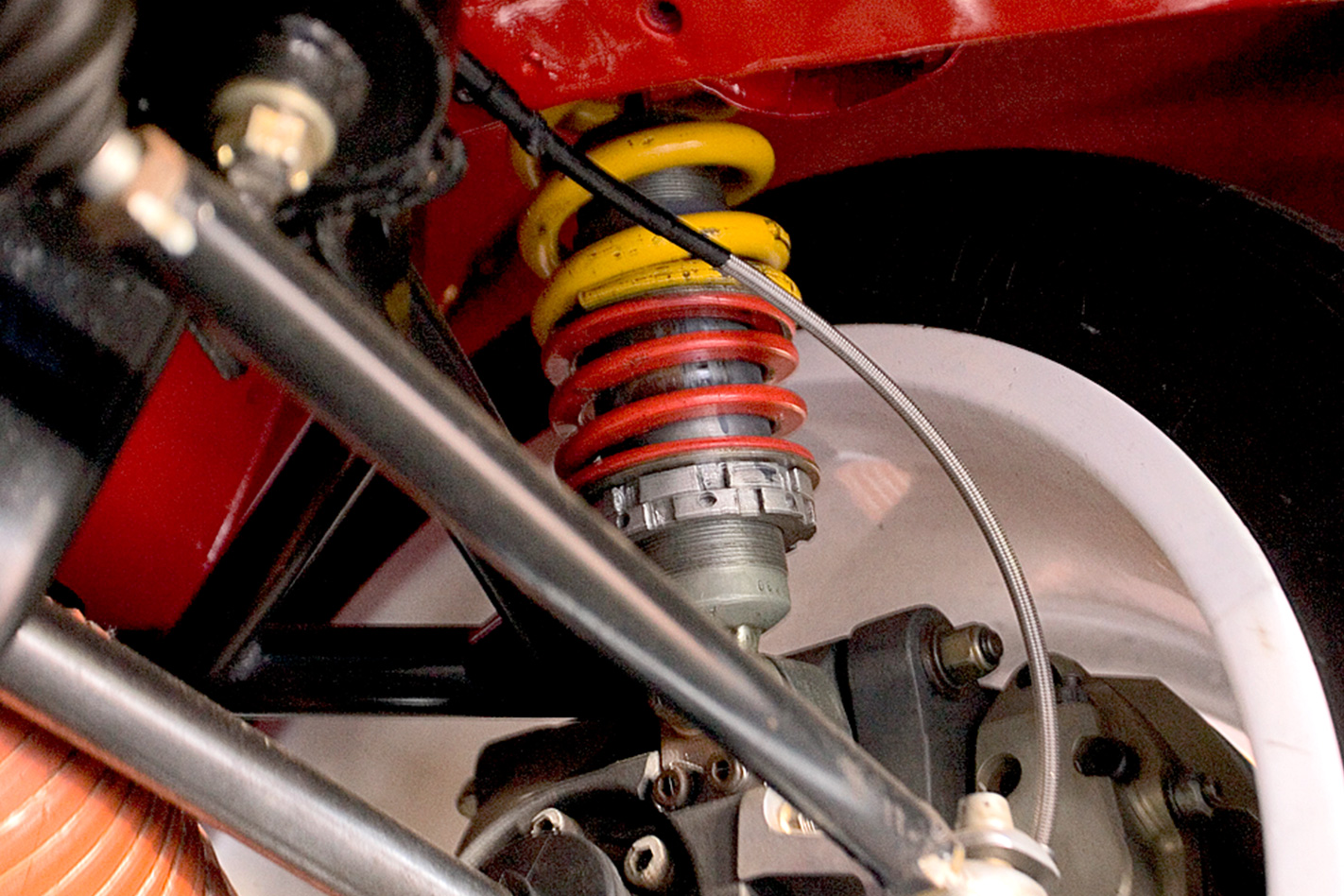

A six-speed gearbox, aerodynamic aids and brake discs the size of family pizza trays completed a spec list more akin to a prototype sportscar. And the road car cost mint: just over $110K in 1992 (for a Nissan?). For the money, you did receive the all-wheel-steer system which was put in the ‘too-hard’ basket for racing. And it swallowed showroom rivals costing twice as much.

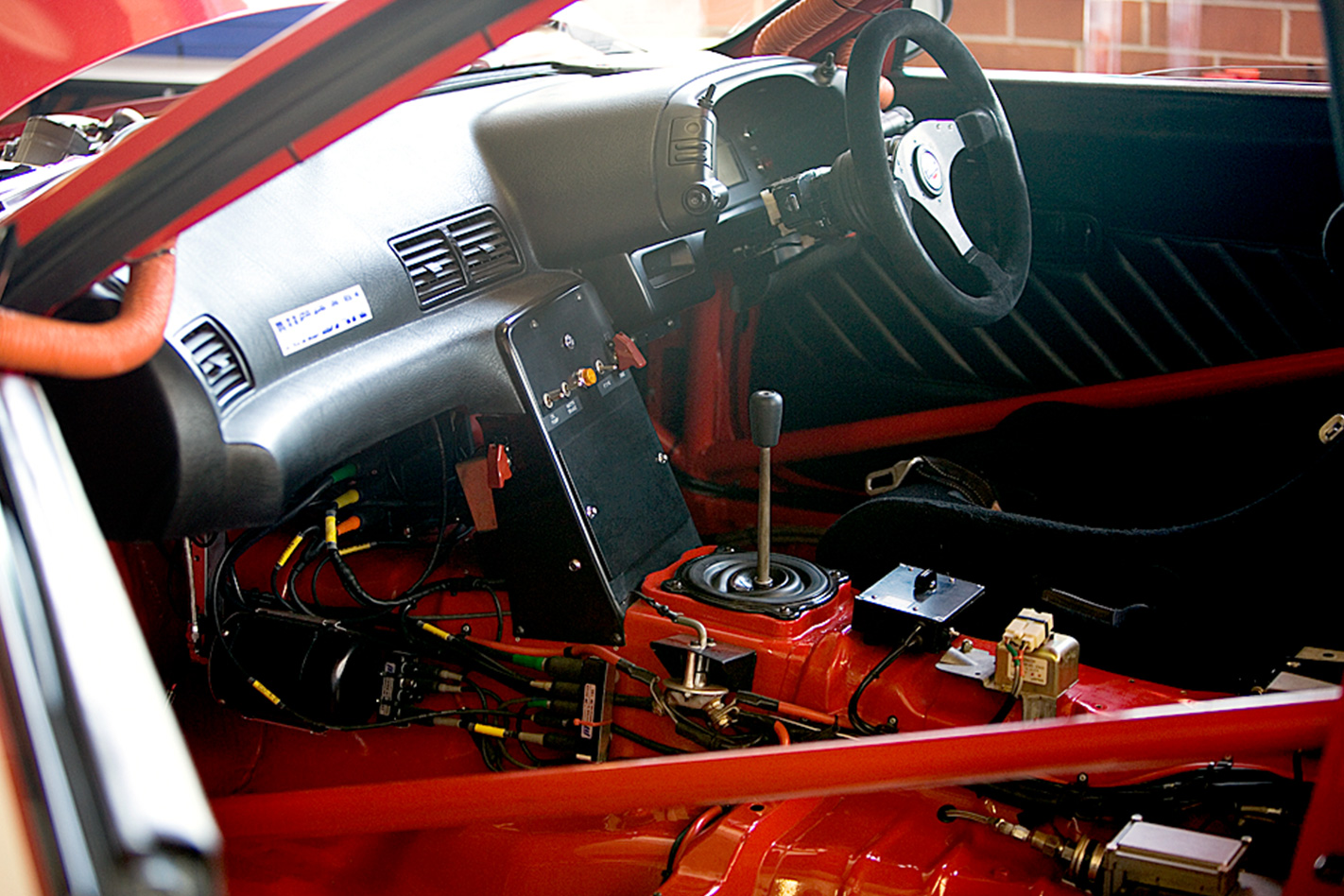

So we had a dial on the console with three modes: ‘mode 0’ for starts, which was rear-wheel drive only; ‘mode 1’ for racing; then ‘mode 2’ when the tyres went off, and that gave you more front-wheel drive. Visiting Japanese engineers couldn’t believe all that. And we did all that ourselves.

“The engine management system cost us a lot of money.” Gibson’s not joking – $600,000 each to build. GMS’s 1992 budget, mostly courtesy of Winfield, was an astronomical $5 million. Seventeen years later half the booming V8 Supercar grid can only dream of such funding. “The car was dominant,” Gibson reflects.

Regardless of the rights and wrongs of those changes, the racing GT-R’s legacy is immense. As the ultimate Group A interpretation, it proved to be a category killer internationally. In Australia, its success fast-tracked plans for a comparatively low-tech domestic V8-engined replacement category, what’s now V8 Supercars.

It also provided the launching pad for the most successful local driver of the last 20 years, Mark Skaife. But that’s another story…