The rollover seemed like a big deal at the time. It certainly got my attention when the horizon went vertical for a fraction of a second before disappearing in a cloud of dust.

It was only a second gear roll, on a dirt track, but second gear in a WRX STI on rally rubber is still quick enough for bad things to happen. The crash was violent but was over quickly, unlike the seemingly never-ending tumble-dryer terror of a high-speed multi-roll crash I had a few months later (RIP my sweet Datsun 1600).

This time in the STI, when the dust cleared, the horizon reappeared in the position it was supposed to be. There was no fire, thank goodness, but I could see the bonnet was crumpled. I shut off the engine and let out a muffled curse in my helmet. I only had a sore neck, but the damage to the car, a blue 1998 two-door STI, was worse than we first thought. Dad and I grappled with the fact it might have to be written off.

That hurt because we both loved the car. Dad worked on it for countless hours in my garage, in the freezing cold and stifling heat. I would help with the heavier parts and the fiddly actions that required four hands, but mostly I just passed him spanners and watched. We talked – especially when I brought him tea and biscuits.

That hurt because we both loved the car. Dad worked on it for countless hours in my garage, in the freezing cold and stifling heat. I would help with the heavier parts and the fiddly actions that required four hands, but mostly I just passed him spanners and watched. We talked – especially when I brought him tea and biscuits.

Then, on race day, I would drive the ring out of the car; absolutely confident it would not fail me. At one brutally rough track I was six seconds a lap clear of the field, thanks to my lack of mechanical concern and confidence in Dad’s homemade shrapnel-proof sump guard.

He was a brilliant product engineer at Ford Australia and he was my unfair advantage at the track.

That world ended when I was out shopping and received a phone call from a family friend: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but your Dad has passed away.”

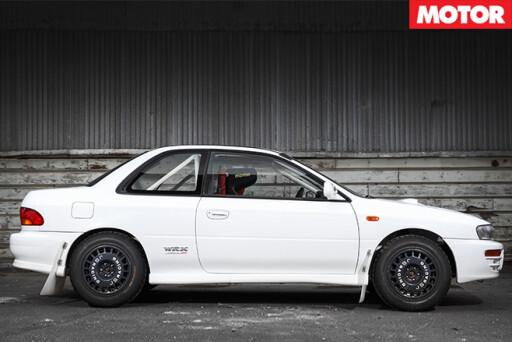

Ten months later I eased up to the start line in my STI, thanks to a mate who refused to sell the wrecked car on my behalf and insisted on rebuilding it. It is a mix of fresh and old parts under a new body shell, but still feels familiar. I have done this procedure so many times. I drop in through the roll-cage, fire up the engine and move towards the start line.

Ten months later I eased up to the start line in my STI, thanks to a mate who refused to sell the wrecked car on my behalf and insisted on rebuilding it. It is a mix of fresh and old parts under a new body shell, but still feels familiar. I have done this procedure so many times. I drop in through the roll-cage, fire up the engine and move towards the start line.

I tighten my helmet and do the five-point harness up so hard I can only just breathe. Then, on the start line, I press the intercooler spray switch and prepare to launch. The procedure might be the same, but everything else is different.

Have you ever cried in your helmet? Well, I did, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. The first run in the car felt so good. To get out and do something that used to bring so much joy is fantastically therapeutic.

But I had to cross the finish line and return to the pits. Normally, Dad would walk over slowly and tell me my time and pass on some information, offer advice and sometimes, praise. Of course, the heart attack meant he wasn’t there and will never be there again. He won’t be in the passenger seat on the long journey to and from each event either.

And that is why I’m not sure what to do with my rally car. Competing without my Dad there just isn’t the same. But I’m not going to get rid of it for now. I can’t.

And that is why I’m not sure what to do with my rally car. Competing without my Dad there just isn’t the same. But I’m not going to get rid of it for now. I can’t.

My two-year-old son just adores it and often orders me to start the engine just so he can listen. He doesn’t talk much, but says “rally car” a lot. I won’t push it, but if he’s still interested in racing when he gets older, I’d be glad to stand there in the pits waiting for him to come back in.

COMMENTS