FIFTY years ago, a French car was en route to victory in a mammoth event set up to showcase the British and Australian motor industries.

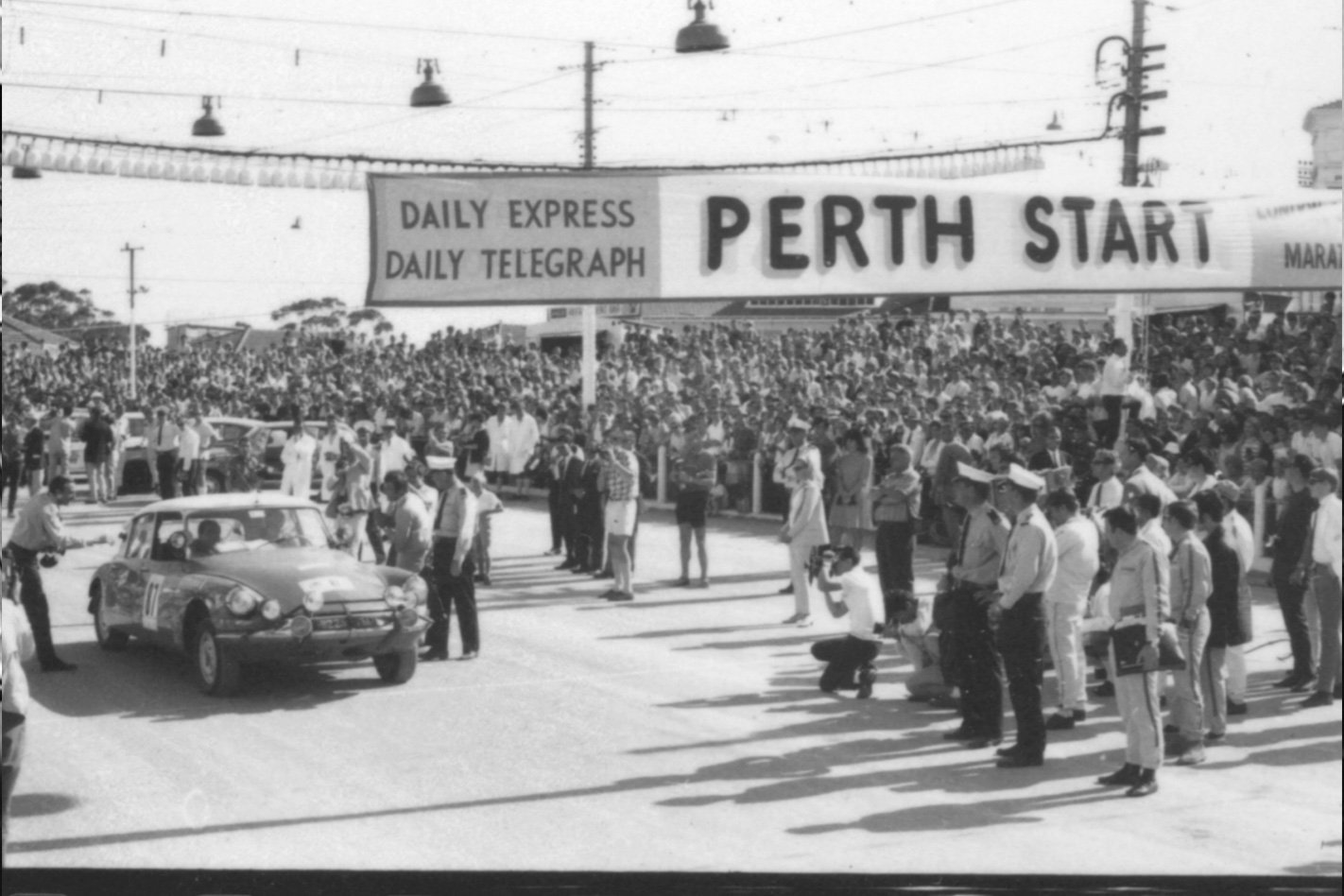

The 1968 London-to-Sydney Marathon, the first and still greatest of the ultra-marathon car races (not rallies), was a gift to the car makers from Britain’s leading newspaper, The Daily Express. Its proprietor, Sir Max Aitken, a Battle of Britain fighter ace, was staunchly supporting Britain’s isolationist policies against a massive push to join the European Common Market – and a win by an Austin, Ford Cortina or even a Hillman would be a huge call to arms. But on the last night of competition, after more than 16,000 competitive kilometres over just 10 moving days (do the maths), a French car was leading, followed by a German one. The first British car was a relatively distant third. It was, from Aitken’s perspective, a disaster.

On the last competitive stage, the German Ford Taunus driven by Flying Finn Simo Lampinen failed spectacularly in a bust-or-bust-through lunge, elevating a British car to second place. But Belgian Lucien Bianchi in a works Citroen DS21 emerged from the last night of frenetic activity with an unassailable 11-point lead and was cruising to the finish at the Warwick Farm Grand Prix circuit. Then he was crashed out of the event by a head-on collision with a spectator’s car.

Author John Smailes covered the marathon in 1968 and co-wrote a book, The Bright Eyes of Danger, with Australia’s first touring car champion David McKay, who led the Holden team in the marathon. Half a century on, Smailes has written its sequel, Race across the World (released this November to coincide with the anniversary), which, for the first time, tells the stories behind the world’s greatest long-distance car race. Publisher Allen & Unwin has given Wheels an exclusive inside view of the crash that saved the British motor industry. It’s a story that’s never before been told.

“THE CRASH was deliberate.”

The small man, grey hair cut short, with eyes so piercing they drill you, was unwavering in his assertion.

“The car that hit us was deliberately there. The crash was not normal.”

We had met in a cafe in Marseille airport, a cheerful place decorated in the manner of the ’60s.

Jean-Claude Ogier and his wife, Lucette, had driven up from their holiday home at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer and I’d flown in from the UK on a tight schedule. Our meeting was to review their part in the greatest road race of modern times – the 1968 London-to-Sydney Marathon.

Ninety-eight crews raced across half the world in pursuit of a total prize purse of 22,650 pounds – a huge sum fifty years ago equivalent to almost $500,000 today. Ogier had almost won it.

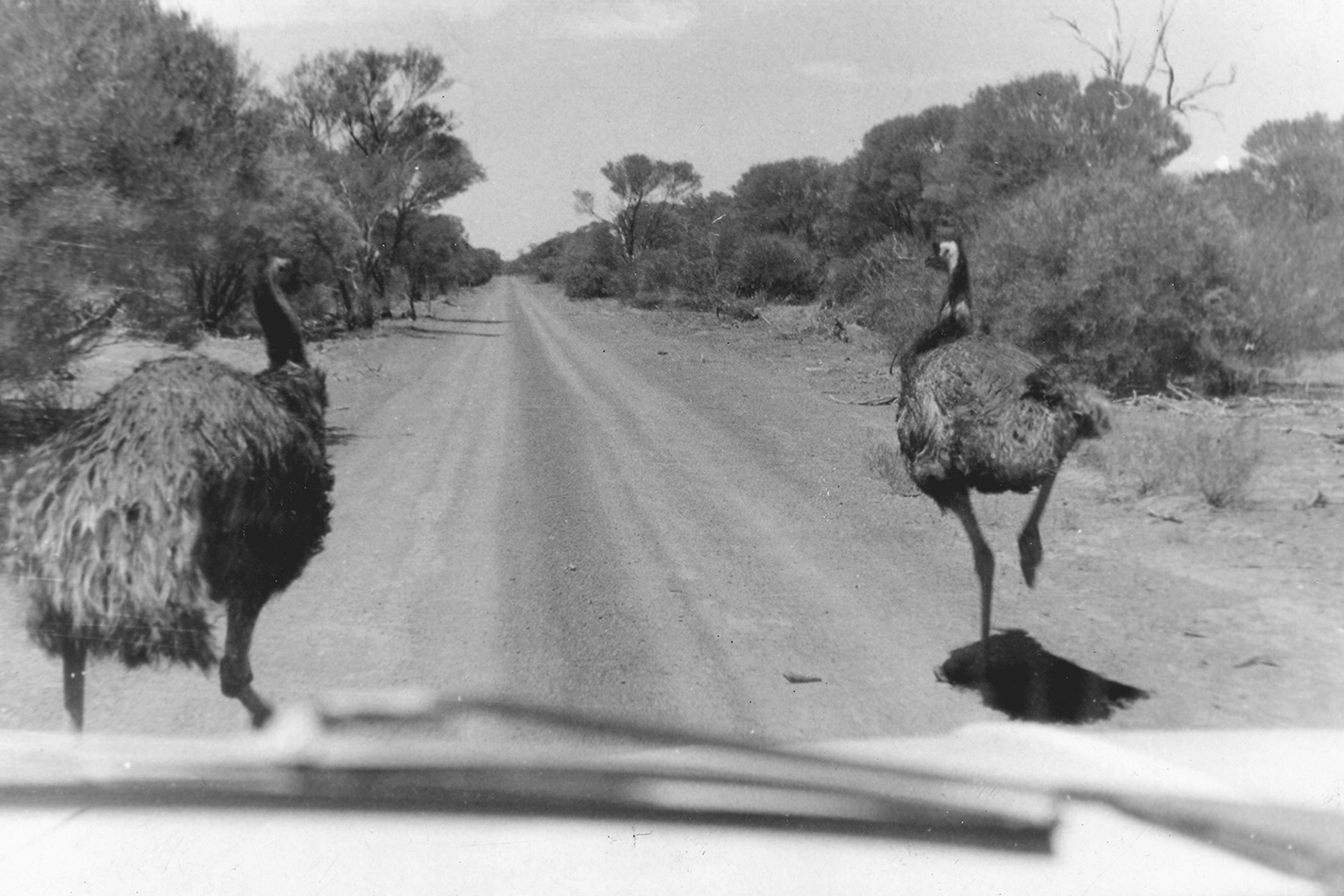

Driving with Belgian ace Lucien Bianchi, winner of the Le Mans 24 Hour race only two months before, the Frenchman was in sight of victory. The pair had kept their lightweight Citroen DS21, a real rocket, in touch with the lead all the time. They’d been third at Bombay, and across Australia had kept their head, as a firestorm of desperate competition burst out around them. That tactic had delivered them outright first, but it was tenuous.

At midnight on the last day of competition, just 12 points separated the top six competitors. Bianchi and Ogier’s gap was only two minutes, and each minute was worth a point. It was too close to call, and there were 694 competitive kilometres remaining. Bianchi, the lead driver, took the wheel. Formula One driver, sports car ace, rally expert – he was masterful that night.

When the team reached Hindmarsh Station, the last competitive stage on the near 17,000-kilometre journey, they were 11 minutes ahead. Bianchi had massively consolidated his lead. It had been a night of legend, a fitting climax to a glorious adventure. It was the expectation of all crews that the real marathon had finished and that they would now cruise to the finish. Ogier took over and a tired Bianchi settled down in the right-hand seat of their left-hand-drive car.

It was early morning, just coming up to 8:00am, and they had two hours and one minute to cover the distance to the time control outside Nowra, an average speed of less than 80 kilometres per hour. Seventeen kilometres back from the control was Tianjara Creek, the last obstacle on the course. Ogier cleared it, not gently but with spray flying. It was an act of celebration.

Just moments before, a white Mini Cooper S drove unchallenged through the control point at Nowra with two young men on board. Incredibly, it set off the wrong way, in the opposite direction to the oncoming competition cars. The marathon did not close roads and nobody at control stopped them.

Two kilometres down the road from control was John Gowland, manager of the Australian Ford team. “I heard, then saw, the Mini coming,” he said. “I stepped out on the road, waving my hands at him, but he swerved around me and kept going.” Gowland saw and heard nothing more. “Later, Andrew Cowan [in a Hillman Hunter] came through followed by Paddy Hopkirk [Austin 1800].”

There was no Citroen.

Two kilometres after the water splash, Jean-Claude Ogier had been approaching a right-hand bend. It was a big sweeper with room for two cars to squeak past each other. “I was in the centre of the road,” Jean-Claude told me in Marseille, his memory of that moment and his attention to detail still intense. “Then the Austin [Mini] jumped to our side.”

The crash was catastrophic. With a massive tearing of metal and not much energy absorption, both cars folded back to their firewalls, trapping their right-hand occupants. The Mini caught fire. No one saw the crash and no one was in earshot.

Then British ace Paddy Hopkirk, the most famous driver in the event, arrived in his Austin 1800. Co-drivers Tony Nash and Alec Poole leapt from the car and aimed their small extinguisher optimistically at the damaged under-bonnet of the Mini. Miraculously, the fire went out. Hopkirk left his two teammates and sped back to Tianjara Creek to alert a small army of media spectators and a smattering of officials, who rushed to the scene.

Half a century on, Jean-Claude and Lucette, who was also in the marathon, co-driving for the works Ford team, are in no doubt. “I think the Austin [Mini] went on the stage purposely to stop us,” he asserts. “Someone knew there was an accident due to happen,” he claims, handing me a handwritten document in support.

But why and how? Where’s the evidence?

“Citroen is very small in the marketplace,” he offers. “A win for it would not be good for sales of the others … People were betting on cars. They did not want us to win.

“The Mini drivers were wearing four-point harnesses,” Ogier continues. It’s as if he thought they were rigged for collision.

“There were so many media there. They must have been tipped off something was going to happen.”

Yes, they were. They were there to cover the stage end of the greatest road race on earth.

Rumours quickly spread from the scene – the one most repeated even 50 years on is that the Mini drivers were off-duty policemen, and intoxicated.

Greg Stanton and Allan Chilcott never knew what hit them. The two 18-year-olds were members of the Campbelltown District Motor Club, just up the road from Nowra.

“Greg knocked on my door about nine o’clock the night before the marathon was due at Nowra,” Allan tells me. “He said we should go and have a look.”

This is the first time, ever, that Chilcott has spoken to a journalist about the crash. He had written a partial explanation for an enthusiast publication, but this is different.

“Greg and I made a pact not to talk. It was better that way.” Stanton passed away from an illness at age 61. Out of a sense of duty, Chilcott has protected his identity all these years. “We were keen to get to Nowra really early, so we decided to go that night,” Chilcott says. “We got our mothers to phone us in sick.” (Both young men worked at the same department store in Campbelltown.)

The next morning, they turned up at control. “It was just a couple of tents at the side of the road. We heard the ETA is one hour, so we thought, ‘Let’s go down to the creek crossing about ten minutes away.’” Chilcott is adamant no one tried to stop them. They just drove off.

“We didn’t see any cars on the road. Thinking back, instead of us it could have been a family going home.” Chilcott describes Stanton as a skilful driver. He claims speed was not a factor. “The road was quite narrow. It would have been a single lane if it had been bitumen. There was a very distinctive curve on its crown. The last thing I remember is the Citroen coming towards us. I don’t recall the crash at all.”

The boys lay in Shoalhaven Hospital with Bianchi in the next cubicle. “No one came to see us; no organisers, no press. We were offered no transport. That night, my parents came down and drove me home.” Fake news had travelled fast. Chilcott’s girlfriend had initially been told he’d been killed. The crash was all over The Sun newspaper that day.

Chilcott tells me he is surprised by Ogier’s accusations. He dismisses talk of sabotage and claims no knowledge of a betting syndicate that would want to influence the outcome of the marathon. “We were just two kids from Campbelltown,” he says. But for 50 years the marathon has “been a big thing on my mind”.

“One day, I was watching a replay on TV of the famous incident when Bathurst 1000 race leader Dick Johnson was eliminated by a rock that tumbled onto the track. I turned to my wife and said, “I know how the rock feels.”

With Bianchi out, Andrew Cowan, his brother-in-law Brian Coyle and British Rally Champion Colin Malkin, in a Hillman Hunter, won from Paddy Hopkirk, Alec Poole and Tony Nash in an Austin 1800 by a margin of just six minutes after 16,694 competitive kilometres in 10 days, seven minutes and nine seconds. Ian Vaughan – a young Victorian trials driver and Ford engineer – was, with Bob Forsyth and Jack Ellis, third in a Falcon GT, six minutes back.

At the prize giving, Andrew Cowan, marathon hero, said: “When you do an event like this there’s got be a lot of luck in it. But as far as I’m concerned it wasn’t good luck that won it. It was bad luck that lost it.”

Even as Cowan was speaking, the UK House of Commons was passing a resolution noting ‘with pride the success of British drivers and British cars in the London-to-Sydney Marathon’ and congratulating ‘the British Motor Industry for making the best cars in the world.’

Three months and fourteen days after his marathon crash, Lucien Bianchi, still recovering from his injuries, crashed his 3.0-litre Autodelta V8 Alfa Romeo 33/3 prototype while testing for his Le Mans defence. He died instantly. Lucien was the great-uncle of Jules Bianchi, F1’s last fatality, the young member of Ferrari’s elite Driver Academy who died as a result of injuries sustained in the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix.