China looms over the global automotive industry like the Death Star over some tiny moon sucked, like so many others, into a slavish orbit by the pull of its wealth.

Media coverage of the car industry might focus on electric and autonomous vehicles – EVs and AVs – but China remains the real story.

China is the world’s largest consumer of cars by a huge and growing margin. And like the Death Star and Darth Vader, one person is in charge. The world’s biggest car market is not a free market but a command economy. President Xi Jinping (or one of his minions) can and occasionally does dent the huge growth and profits the Western carmakers have seen in China with the stroke of a pen and the imposition of a new tax or regulation.

The cooperation between carmakers, cities and regulators required to make autonomy actually work is hard to achieve in the democratic West. Xi could simply order it, and give China a huge lead there too. Chinese-made self-driving cars might not be an appealing vision of our motoring future. But it wouldn’t be a bad bet.

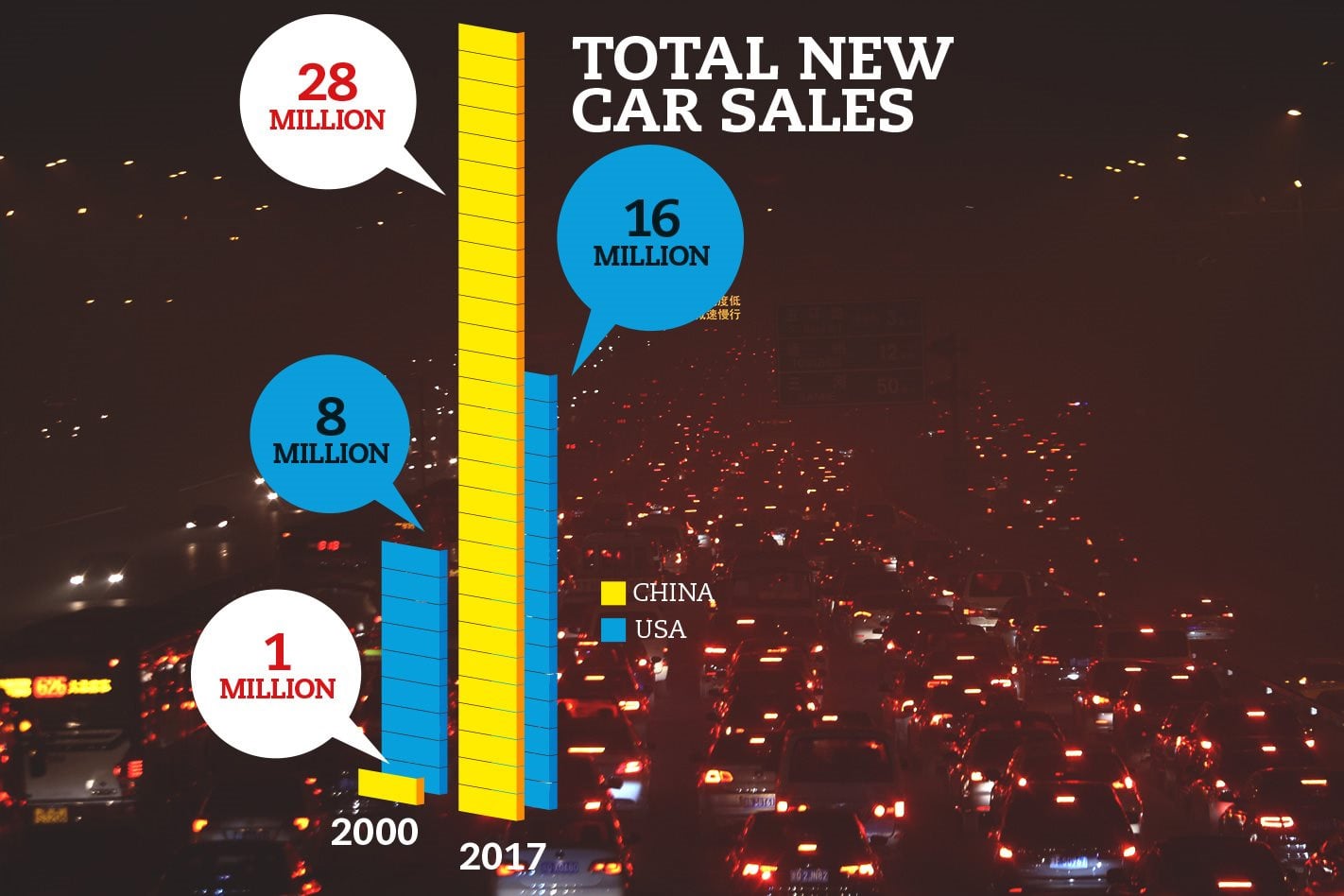

So how big is China? In 2000, around a million cars were sold there. By 2017, that figure had risen to 28 million. China overtook the United States in new-car sales in 2009 and now exceeds its nearest rival by around 12 million sales each year, despite America’s impressive post-crash recovery.

Jaguar, however, dodged another bunch of taxes by starting to build its cars in China and saw sales leap 300 percent. You make money here at the pleasure of the government, and good luck with that business plan.

The big winners have been General Motors and Volkswagen, both of which invested in China when only the government was buying cars and annual sales were about the same as Lichtenstein’s. To avoid punitive taxes, foreign carmakers must build their cars in China in 50-50 joint ventures with local companies and with certain combinations of components made locally from scratch, the (clever) idea being that the local firms learn from the foreigners, and the foreigners have to invest heavily and can’t just up sticks when they get tired of the madness.

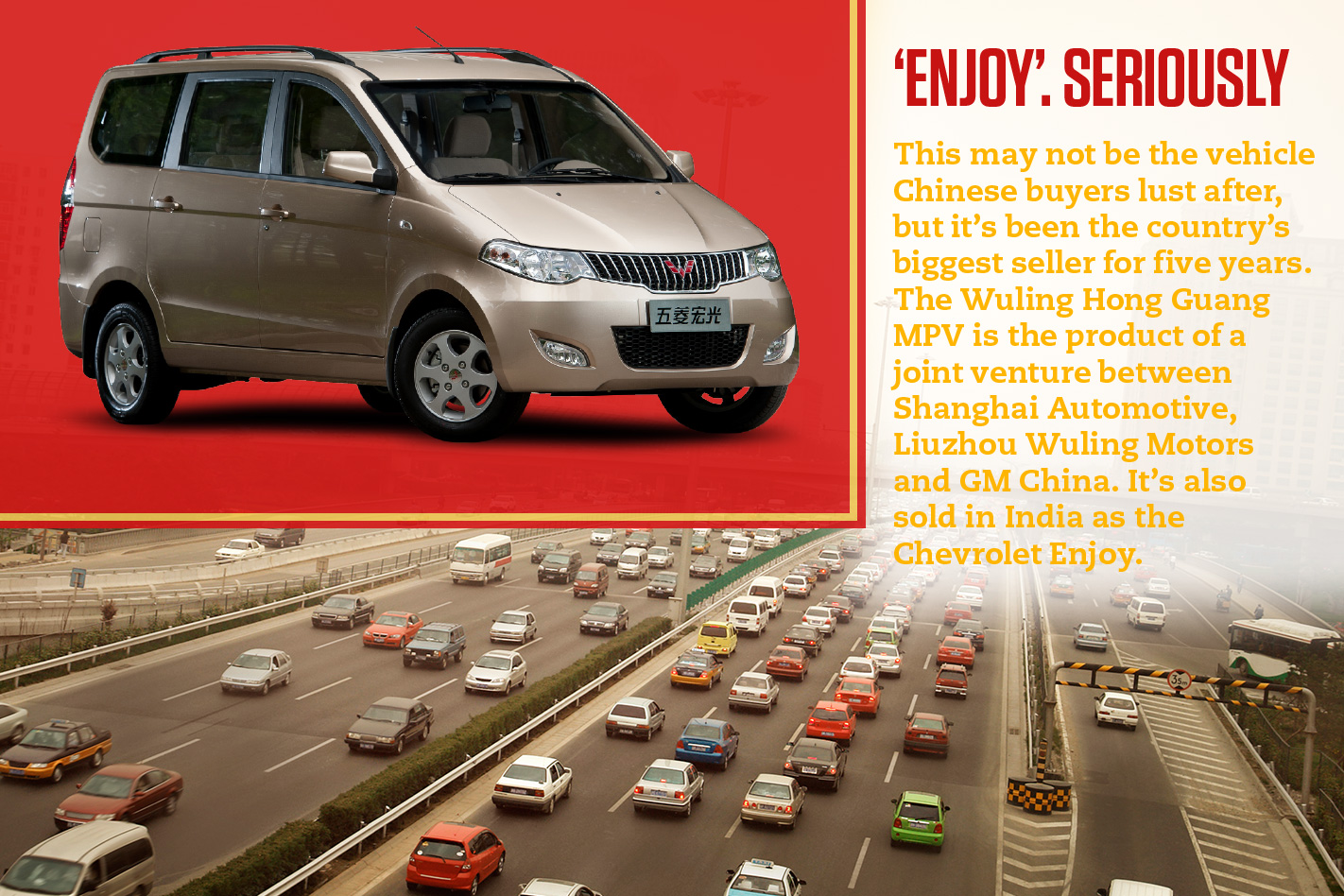

So what do Chinese buyers want? Nobody really wants a Wuling Hong Guang, but this shitbox mini seven-seater has been China’s biggest seller for five years for its low price-per-pew. The rest of the top ten is a mixture of compact saloons based on old GM or VW Jetta platforms (three of the latter alone) or compact SUVs from local brands like Haval. It’s SUVs that Chinese buyers actually want, growing from less than five percent of sales a decade ago to 40 percent now and 60 percent by 2020.

Until its sub-boom in SUV sales, China didn’t have much impact on cars we can buy here. Mass-market Chinese cars were either unique to China, like the Hong Guang, or repurposed last-gen Western models like those Jettas. The premium carmakers sold their standard ranges, plus some local-market oddities like the long-wheelbase 3 Series: cheap labour means some buyers can afford a chauffeur but not a 5 Series.

For a while, the Western carmakers worried that their Chinese partners, engorged with profit and having learnt how to make quality cars through the joint ventures, might launch an assault on their home markets as the Japanese and Koreans did. That hasn’t happened at scale, despite Chinese government encouragement.

Firstly, Chinese cars made without Western help remain sub-standard, as one independent tear-down analysis proved. And secondly, Chinese carmakers just aren’t that excited about the often flat traditional markets when their own is forecast to take off again as mass car ownership expands inland, away from the rich coastal belt.

Direct Chinese involvement in Western markets is more likely to come from the purchase of weaker Western brands – Geely has bought Volvo and Lotus – or from a state-backed doping program that ensures Chinese firms win the race to full autonomy.

Because of its scale, China is the world’s biggest buyer of EVs, but their high price and a limited charging network means the government is easing back on the targets it had set, and it’s wise enough not to clamp down on sales of conventionally powered cars just as millions of its citizens become able to afford them.

China’s emissions will continue to grow, its increasing EV sales being massively offset by its SUV surge.