Remember Andie MacDowell in Groundhog Day? Poor old Bill Murray took a fearful caning in his attempts to play the beast-with-two-backs with her and some people wonder why.

See, if you break Andie down into her component parts, there are a few, erm, unconventional bits. The smile’s a bit goofy, the teeth are from a larger mammal and even the frizzy hair is the sort that most teenage girls spend hours trying to straighten.But put all those slightly off-centre components together, and Andie MacDowell is eight shades of luvverly. More than the sum of her parts is an understatement. And without wishing to defame either La McDowell or the vehicle on these pages, the Porsche 356 is more of the same.Break it down into its individual components and the sides are too slabby. The whole profile owes more to an upside-down wheelbarrow than it does a wind-tunnel, and the slitty side glass makes a gun-turret feel airy.

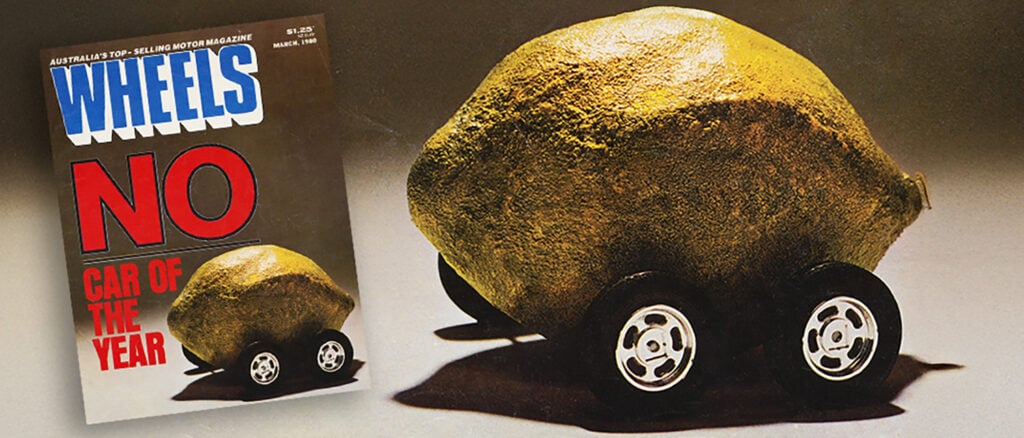

Mounting the engine way beyond the rear axle should make it a rock-on-a-string to drive, the petrol tank sat in your lap should make it an agate-bomb in a frontal hit, and even the air-cooling seemed oddball at a time when liquid-cooling was hardly a black art. Just like a bee shouldn’t fly and frizzy girls with goofy grins shouldn’t appeal, a Porsche 356 just shouldn’t work.Absolutely none of which explains why the 356 is such a glorious, enduring piece of design with styling that, however flawed, has become nothing short of iconic. And if you’re ever lucky enough to drive one, you’ll also know that the experience is an involving, tactile triumph. Um, yeah, we like them.

Mark Webber’s Porsche 919 Hybrid in London The 356 was Porsche’s first production car and it was born in 1948 in Gmund. What’s so strange about that? Well, Gmund isn’t actually in Germany. In fact, it’s in Austria, but the less said about influential Germans born there the better. Ironically, Porsche only moved to Austria during the war to avoid the Allied bombers over Stuttgart. It was a tiny affair at first with only 50 cars or so built in the first year.By 1950, Ferry Porsche (son of company founder Ferdinand) moved the whole shebang back across the border and set up shop in Zuffenhausen, a suburb of Stuttgart (which the company still calls home). In those days, the 356 used a lot of technology that would be familiar to VW tragics, as Ferry’s dad, Ferdinand, designed the Beetle.Porsche Senior was actually banged up by the Allies in 1945 as an accused war criminal. He spent 20 months, without trial, in a French prison.

The fact that he won the 1937 German National Prize for Art and Science, as well as designing some pretty handy tanks for the Nazis, did him no favours but it did make the Allies realise he had a bit going for him as an engineer. Ferry was arrested, too, after the war, but was let off with a warning.While Pa was doing porridge, young Ferry kept the business running by repairing cars and working on anything from water pumps to winches. Eventually, the company scored the job of designing a racing car which raised enough money to spring Ferdinand from French Sing Sing.Those early Gmund-made cars are now rarer than a happy day in a Frog prison, but the ones that have made it through have probably done so because their bodies were made from aluminium rather than the steel of the later, true, production cars (the Gmund models were all hand-made).Even then, Porsche was concerned with weight and, just like Colin Chapman’s on the other side of the ditch, the cars that resulted made a heck of a lot from not much. And in those days, not much meant a 30kW 1100cc engine borrowed from VW.

Porsche teaches the perfect driving position While early 356s used a lot of VW parts, by the ’50s, Porsche had re-engineered the important bits and there was virtually no commonality between the two despite sharing the same basic layout.Cars built up to 1954 are the ones for the real purists out there. Known as Pre-As, you’ll spot them by their two-piece windscreen (which used a strip of metal to split it until 1952 and then became two butt-jointed pieces of glass for 1953 and ’54).The car known as the 356A turned up in 1955. Running changes resulted in the more refined second version for 1957 and even more changes and improvements brought us to the 356B in 1959. The last incarnation was the 1964 356C, which featured disc front brakes and the most powerful of Porsche’s pushrod engines, the 71kW SC mill.Despite Ferry’s initial estimate that the world could probably cope with about 1500 356s, the company went on to make just shy of 80,000 over 17 years. As many as half those cars are believed to still exist. Porsche was still selling 356s as late as 1965, two years after the 911 (and 912, which was a 911 with the 356’s flat-four) rolled into town.Part of the 356’s mystique was its racing success. Nothing establishes a legend like a full trophy cabinet, and the little Porsche has scored major success in events as diverse as the Le Mans 24-hour, Mille Miglia and Carrera Panamericana.For the diehards, only a Pre-A or an A will do. They’ve got a point, as the earlier cars are certainly prettier. They’ll also argue that the newer a 356, the less pure it is, but the later cars generally drive better. The front discs of the C made a huge difference and the bigger, more powerful engines of the Bs and Cs didn’t do any harm either.That said, it doesn’t really matter what age or specification of the 356 you drive, because they’re all gorgeous. Straight-line stomp isn’t the point (just as well) but for tactile, direct steering and a taut yet supple feel, not much comes close even today.And if you think that the bigger, heavier cars of today have gone off on the wrong tangent, a spin in a 356 will confirm it. Despite being up to 60 years old, a 356 still points like a good ’un and is light enough to sidestep like a rugby winger, allowing you to keep corner speeds high and make the most of every one of those little horsepowers.If you do score a drive in one, unlike Groundhog Day, you’ll wish you were doing the same thing tomorrow. And tomorrow. And tomorrow.