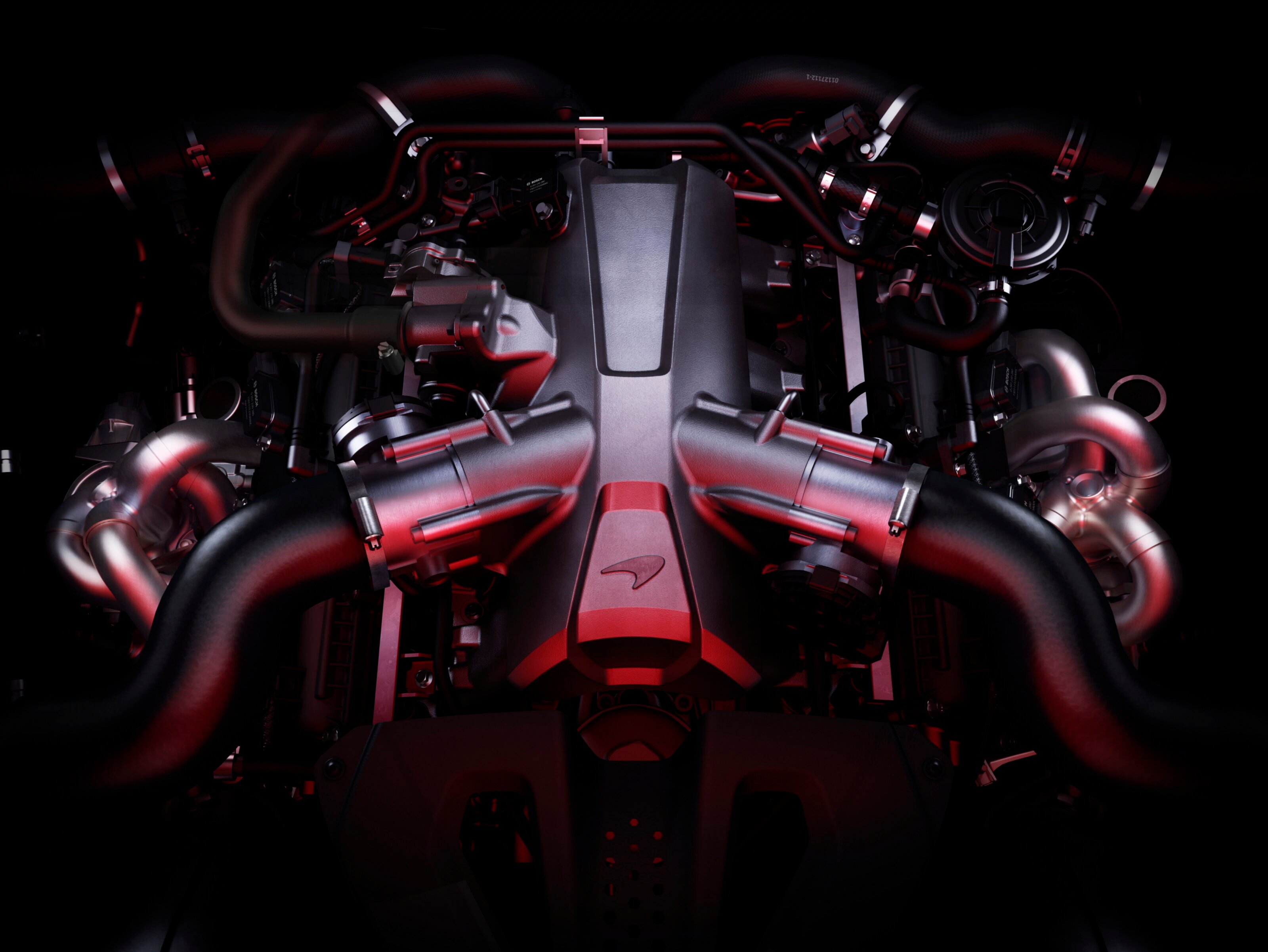

McLaren’s 720S is arguably the definitive modern supercar of our time. One of the characteristics that elevates it above the competition is its engine – a 4.0-litre twin-turbo flat-plane crank V8 producing 530kW and 770Nm.

Dubbed the M840T, the unit is an absolute monster, with seemingly endless reserves of power that it deploys without prejudice.

Despite its all-encompassing charisma, the M840T remains a cohesive part of the 720S’ whole – something we’re discovering with each drive as MOTOR has Woking’s Super Series monster in our long-term test fleet.

But there’s another story to be told with the M840T, one that forgoes the intricacies of throttle calibration and torque curves for the pages of history books and gives a unique insight into how engines can have a lineage as complex as a royal bloodline.

This is the story of how Le Mans race cars and a Japanese automotive giant gave birth to McLaren’s modern supercar family.

The first thing to be acknowledged is that McLaren doesn’t actually build the M840T itself (much like the iconic naturally aspirated V12 that sits mid-ship in the original F1). Instead British company Ricardo is responsible for building the M840T, shipping the completed units to McLaren’s Woking headquarters to be placed into cars. That said, the Woking team has as much ownership over the finished product as if they’d bolted it together themselves.

This is the start of the rabbit hole. Take the Red Pill and you’ll discover that the bones of the M840T are older than the McLaren F1 road car.

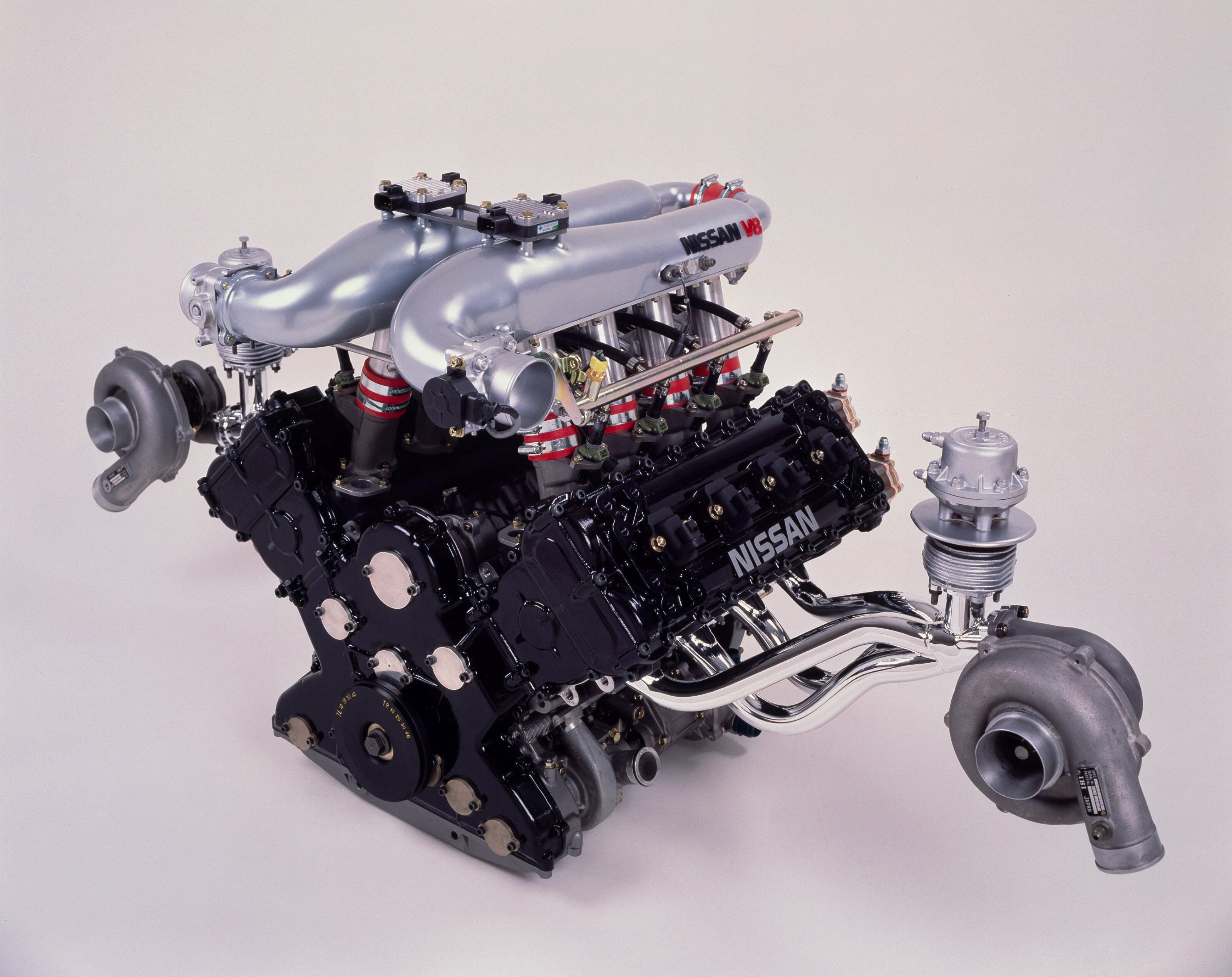

To explain how, we need to wind the clock back to 1987, when Nissan was beginning to work on an all-new engine designed exclusively for motorsport use – namely, the mega-powerful Group C regulations used in global sports car competition.

Nissan wanted a bespoke unit to power its Group C racer to glory at the 24 Hours of Le Mans (which unfortunately would never become a reality).

Yoshikazu Ishikawa designed a 2996cc twin-turbocharged 90-degree V8 with a bore of 85mm and stroke of 66mm. The resulting engine was dubbed VEJ30, and fitted to the R87E race car. Still with us?

Unfortunately for Nissan and Ishikawa-san, the VEJ30 failed to net the desired results.

Enter Yoshimasa Hayashi – a longtime NISMO employee who just so happens to share his name with Japan’s current foreign minister. Hayashi-san took the VEJ30 and made a number of changes including increasing the displacement to 3.4-litres.

The reworked engine was then dubbed VRH30 and used for Nissan’s 1988 campaign. Again, results were found wanting.

For 1989 another all-new engine project was initiated, with development examples being fitted to the R89C Group C racer. The fundamental ingredients remained, but with Nissan’s engineers finally building something that lived up to their expectations – the VRH35.

This is what would eventually, after two decades and an entirely different Le Mans prototype program from Nissan, be used by McLaren as the heart of its sophomore creation, the MP4-12C.

The leap from Group C to road car is a substantial one, even for vehicles as fast as a McLaren.

Bridging the gap is the R390, a GT1 machine built by Nissan to compete at the 24 Hours of Le Mans under the aforementioned GT1 rulebook.

We won’t get too deep into it, but the R390 itself was somewhat of a reskinned XJR-15, with the two sharing the same designer in Tony Southgate, and were run by Tom Walkinshaw Racing.

GT1 regulations at the end of the 20th century demanded that road-going homologated versions of the race cars be built and sold to the public. It was an open secret that manufacturers competing in GT1 were driving double-decker busses through various loopholes that regulated this part of the rules, but appearances had to be kept up.

To appease the powers that be, Nissan did build a red prototype version of what it planned to sell to the public. This was then repainted and given an entirely new VIN to become the blue ‘long-tail’ road version that many will be familiar with from its time in the Gran Turismo racing games.

Nissan never actually sold a single R390 road car. To this day there remains conjecture if it ever actually intended to. We won’t delve into that convoluted maelstrom of speculation, but what’s important is that the VRH35L was never released on-road.

Once the R390 project was finished with, the VRH35L was put on a shelf to collect dust. Yes, other VRH engines were built by Nissan, but the twin-turbo king was taking an indefinite nap.

That was until the late-2000s when McLaren started looking for suitable engines to place into its first road car the MP4-12C. McLaren has built its reputation as an engineering company, but didn’t quite have the capacity to take on an entirely bespoke engine alongside its chassis development duties.

A modified VRH35L was developed and placed into a very early development mule built from a Ferrari 360. By this stage, the Nissan engine had increased in capacity to 3.8-litres, with legendary companies Ricardo and Ilmor both having their fingerprints on the project.

When McLaren finalised that it would opt for the twin-turbo V8 design, it bought the rights to the VRH35L engine wholesale from Tom Walkinshaw Racing. Having done significant work to the engine alongside its engineering partners, McLaren then renamed it M838T.

This engine was used in the MP4-12C, 650S, 675LT, P1, 540C, 570S and 600LT, before a series of additional changes increased the displacement to 4.0-litres, bringing to bear a new name (but the same fundamental design) in the M840T. McLaren claims 41 per cent of the M840T’s components are new compared to the M838T.

Other than the core bones of the block and the 85mm bore diameter, next to nothing remains of Nissan’s VRH35L in the M840T. However, it is muddy at best to describe either of the Woking units as ‘all-new’ given their lineage. Both Nissan and McLaren’s engine’s have developed worthy legacies in their own right.

This twisted mechanical history creates an intriguing historical paradox, where McLaren’s most powerful modern road car engine competed against the F1 GTR and its 6.0-litre S70 BMW-sourced V12 at Le Mans in 1997 and 1998. Sometimes history can be stranger than fiction.

We recommend

-

TV

TV2019 McLaren 720S vs Great Ocean Road by night

Andy Enright takes on Victoria's coastline by night in the manic McLaren 720S

-

Features

FeaturesThe Artura is McLaren’s most important car since the F1

A decade of knowledge is distilled beneath the McLaren Artura’s sheet metal ... welcome to Woking’s V6 hybrid era