Most of the time on most technologies, the rest of the world’s car companies take their lead from Germany.

Germany’s three premium brands live and breathe in the sweet spot between volume and margin, so they can let their geeks wander down research and development paths that would be too flippant for mass production or too risky for a Ferrari or even a Jaguar to follow.

The technologies then take anywhere from half a generation to a generation (so, between three and seven years) to make it to global volume brands. Sadly, the news from the Big Three Germans isn’t good for the future of naturally aspirated engines.

The same thing goes over at Audi, where you can buy cars with turbo, biturbo or supercharged engines, but you won’t get natural aspiration until you reach up into the rarified air of the RS4 or R8. Even then, the next RS4 is going turbo and the next R8 won’t have the 4.2-litre atmo V8, so the 5.2-litre V10 will be the last one the brand ever offers.

Benz has turned its back on atmos, too, though there are hints that an atmo straight-six power might return with the next E-Class. But it seems unlikely.

Where did it all go wrong? There was talk, of course, and there was a drift back to turbos in the early noughties, but the immensity of the threat to the future of atmo engines really hit home during the Frankfurt Motor Show about six years ago. During an interview with M-B’s engine boss, Bernard Heil, he was chatting about the downsizing of engines, which we’d heard about before.

Downsizing had become a fast, easy, affordable way for carmakers to meet more stringent emissions laws from not just the European Union, but from the California Air Resources Board (and the 16 other US states who copy the west-coasters’ regulations), China’s State Environmental Protection Administration (which typically follows in the wake of the EU) and Japan’s Ministry of the Environment.

Then, with the introduction of EU regulation number 443/2009, it all got serious. It demanded an average CO2 figure of 130g/km for every marque by 2012/’15 (stretched out over three years to account for model cycles). Ouch.

Not that the car companies minded too much, especially the Big Three, plus Volkswagen, Toyota and PSA. New rules demanded new technologies and new technologies were marketable. Variable valve timing. Twin-scroll turbos. Variable-geometry turbos. Cylinder On Demand. Direct fuel injection. Sodium-filled valves. On-demand ancillaries. The list goes on.

So downsizing is a thing, confusing alphanumeric naming structures the world over. Three-cylinder engines are the new industry buzzword, with BMW even tossing one into the i8 sports car. Audi, Ford, PSA and Volkswagen swear by them. Fiat even boasts of its two-pot screamer, though its real-world economy benefits are, at least anecdotally, scant.

What our Mr Heil told us, that we hadn’t heard about before, was downsizing’s more potent stablemate, downspeeding – lower revs, ever lower revs. And he just let it slip, almost accidentally, into a conversation in a way that indicated he’d been tossing it around at work for years. Which he had been.

But Mercedes-Benz has since backflipped and will even fit a three-cylinder engine to its next E-Class…

The more we dug, the more we saw it wasn’t just Mercedes, either, because downspeeding is now a thing at the other two Big Three Germans. Former BMW board member of development, Herbert Diess, has admitted to MOTOR downspeeding could become more extreme than anybody credits, especially in mass production. “To get below 80 grams we will need longer gearboxes and down-speeding engines,” he said.

“Initially that will mean 1800-2500rpm for internal combustion engines (ICE), but it will really mean 800-1500rpm in the longer term. That’s where the ICE has to go in the future to meet those kinds of numbers. High torque, low revs, higher injection pressures and probably electric power to boost at low speeds.

“We all knew this was coming. When we kept MINI as a brand one of our major motivations was our fleet CO2 emissions.” Sadly, those same fleet CO2 averages must include quattro, M and AMG. All three sell only turbocharged cars (with the exception of the outgoing C63, the RS4 and the R8), though all three also have hints of a future that might save atmo engines.

“But the concept that we pursue in all our segments deserves turbocharged engines and that’s what we are focused on. So, no more atmo.”

It’s the continuing quality and cost improvements of turbocharging that are cruelling atmo engines. The cost of turbochargers has come down dramatically in the last decade and their efficiency continues to climb.

Turbos of today aren’t like yesterday’s. They can change the geometry of their vanes to ward off lag. They are so precisely controlled that the power delivery is more or less instant. They deliver hard, early, then happily fade out, with sequential turbos then climbing in to help with higher revs.

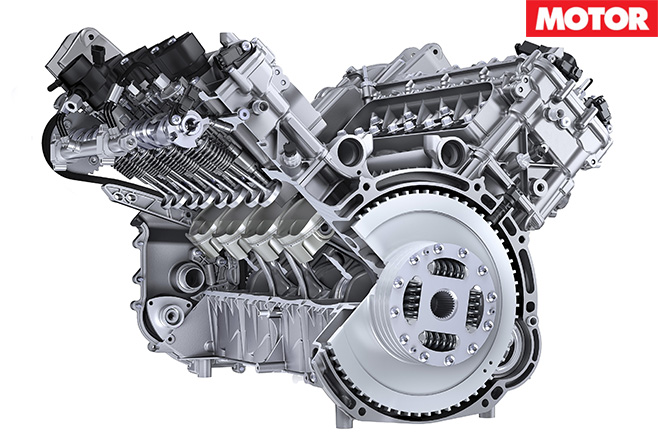

The packaging isn’t always easy, with extra space needed for cooling circuits, intercoolers and the turbo itself. BMW, Audi and Benz have all migrated the turbos inside the vee of the their V8s. One Audi engineer told me for all the talk of shorter tracts and better throttle response, the real reason was packaging.

But the beauty of the turbocharger in context is when it’s not being boosted, the car can deliver (almost) the fuel consumption of a smaller engine. Then punch hard like a big one.

The possibility remains that someone might do a cut-price Porsche 918 and combine an atmo motor with electric power for low speeds, like a lag-less turbo, though it’d be a long-odds bet.

The tantalising prospect is an electric ‘turbo’ might save the atmo engine. Or at least its characteristics. It still force-feeds air into the engine, but operates instantly and with fewer heat and packaging constraints.

The V12s are the last holdouts at Ferrari, as they are at Lamborghini. The relatively low volumes mean the V12 model cycles run far longer than the smaller motors, so they will stand longest without turbos. Them and, probably, Chevrolet’s V8.

There is development left in the Lamborghini Aventador’s V12 (it has yet to adopt even direct-fuel injection) and some left in Ferrari’s V12, too, though Aston Martin doesn’t have the funds for its V12. It will, inevitably, be replaced by something from AMG, which owns five per cent of Aston.

But nobody is spending resources to design a new atmo engine from a clean sheet of paper. There might be some upgrading of existing hardware, but don’t expect much more than that. Not only is that fairly sad, but there’s never been a greater reason to appreciate NA engines while they’re still around.