Benedict Chifley, fedora in hand, wore a wool suit minus the usual waistcoat, given Melbourne’s late November weather.

Australia’s 16th Prime Minister was very nearly a day late for this, the launch of the first Holden, but he was never – ever – going to be a penny short. After all, he’d arranged one million pounds of bank loans and invested a good deal of his heart and soul.

This was the realisation of a dream for a country where butter, petrol and tea were still strictly rationed, long after peace was declared.

The former railway engine driver, war time Treasurer and now PM, endured the ravages of the Great Depression and then a war that seared the hearts and hopes of every Australian family.

Now, on 29 November, 1948 – definitely not the 30th as initially scheduled – he was here at the factory in Salmon Street, Port Melbourne to see his efforts made whole. This was a banner occasion for a country of just 7.5 million citizens that only six years earlier was perilously close to a Japanese invasion.

That distant past was indeed a different country. But to understand the present, we need to rewind…

Darwin was hit by more bombs than Pearl Harbour – 681 of them – delivered by more Japanese aircraft. There were 100-plus enemy bombing missions extending from Broome, right across the north, signalling a serious, imminent threat.

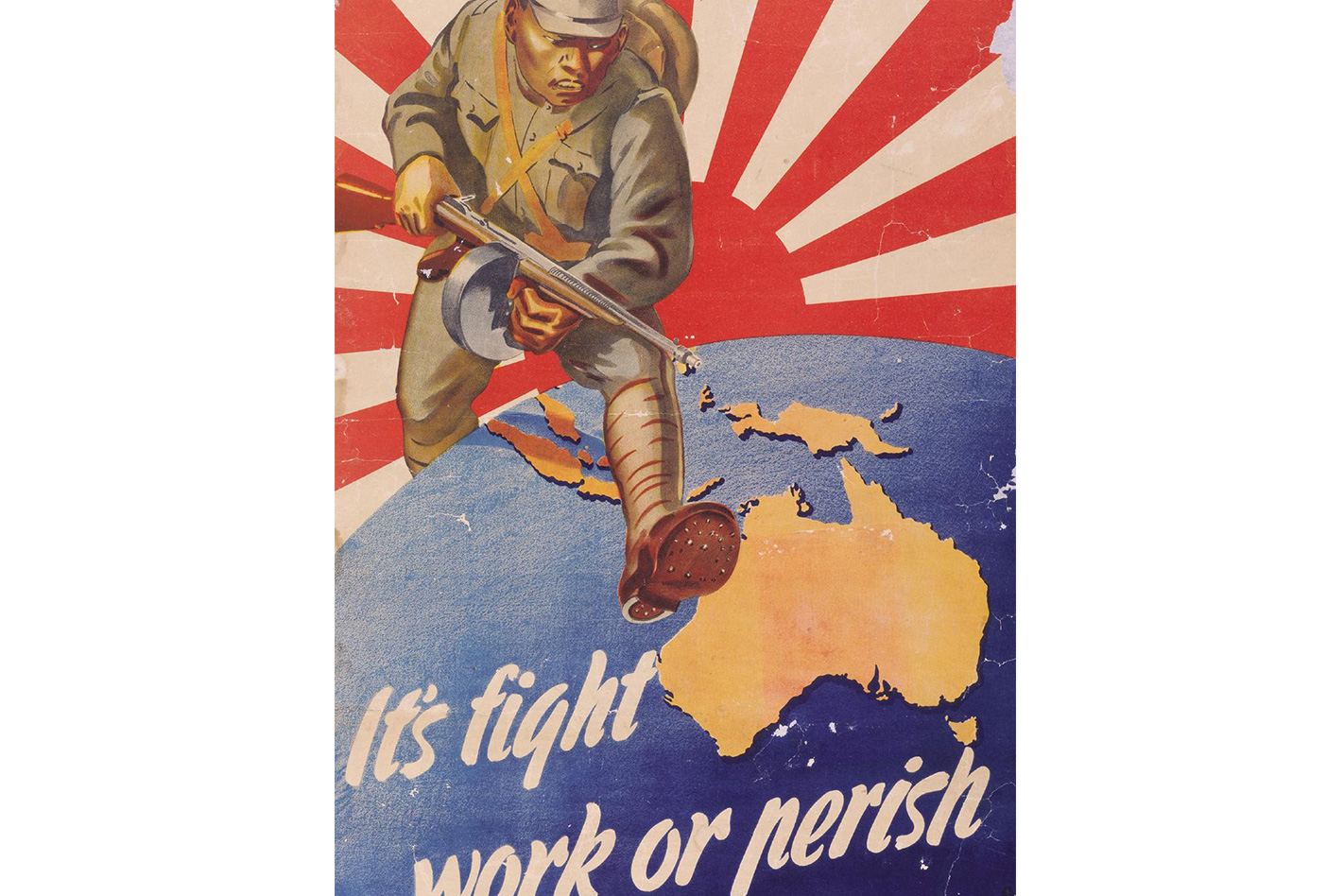

In 1942, our generals were war gaming likely tank battles in the Northern Territory and planning a strategic withdrawal to what they called The Brisbane Line. The railway station posters depicted a charging Japanese soldier: He’s Coming South. It’s fight, work or perish!

At General Motors-Holden, hastily reconfigured factories were pumping out torpedoes, anti-tank guns, aircraft engines and boats, a far cry from their pre-war role marrying Australian-built Holden bodies to imported Chevrolet, Buick, Oldsmobile and British Vauxhall mechanicals.

By the end of it, on VJ Day in 1945, more than 27,000 Australians were dead. Another 30,500 were POWs and 34,000 were wounded. Some grievously, others with more subtle but still potentially fatal issues. My father was one of them.

This farm boy from Ganmain in NSW, drove a Matilda tank, was a reluctant Borneo invasion soldier and remained, until the day he surrendered his licence, a serial Holden buyer.

He was a member of The Greatest Generation, demographic shorthand for those who lived through the Depression and fought World War 2. They shared a huge, visceral relief that it was over and set about the job of rebuilding.

To understand Holden’s bond with post-war Australian culture means understanding my old man’s generation, those stoics who transformed this place from a pastoral past to a modern future, under leaders like Chifley. For them, the first Holden was a national project; a cross between the Snowy Scheme and the Royal Flying Doctor service. This was something to swell the chest and wrap tightly in the flag, and it made the betrayal of the 1980s so much harder to accept.

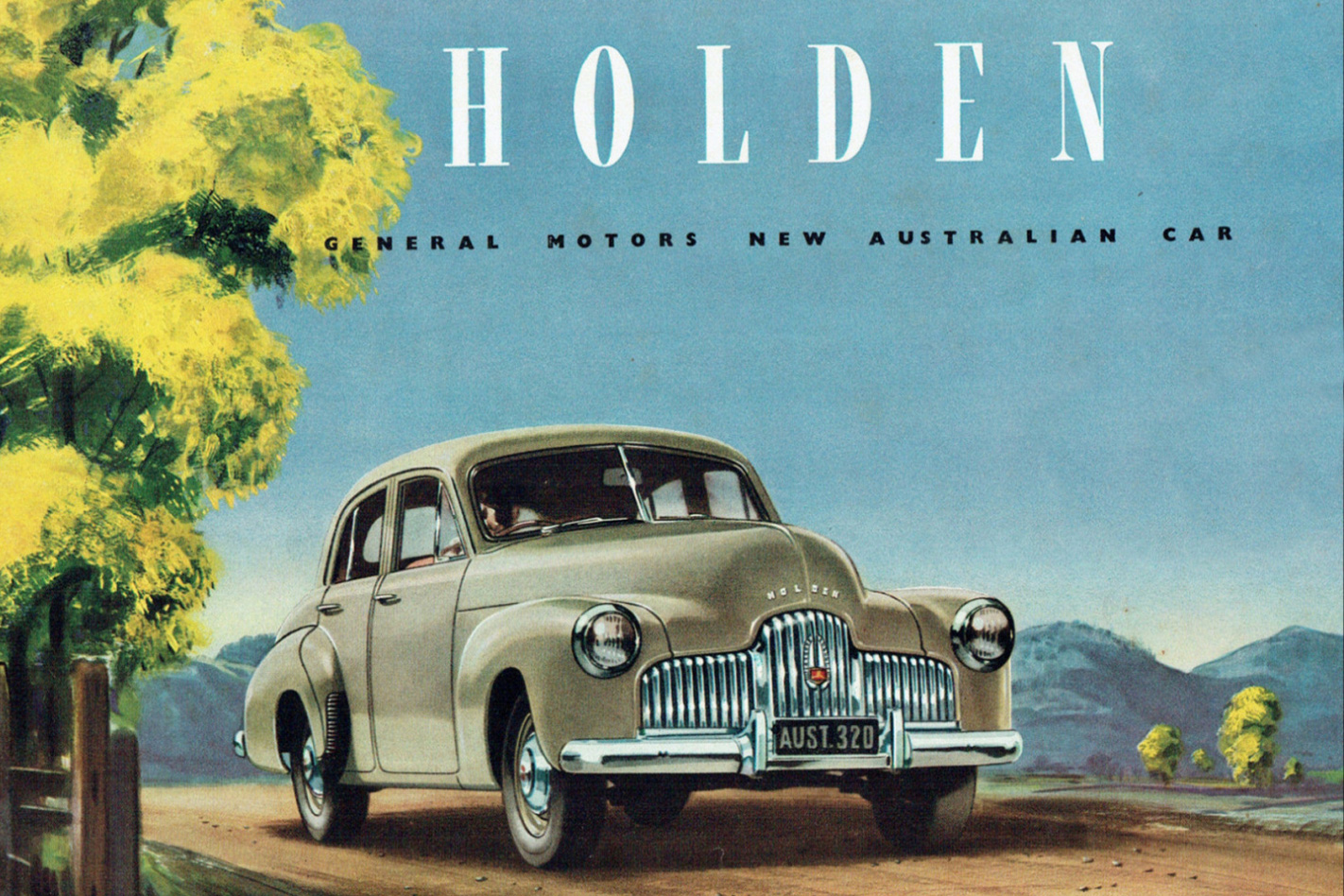

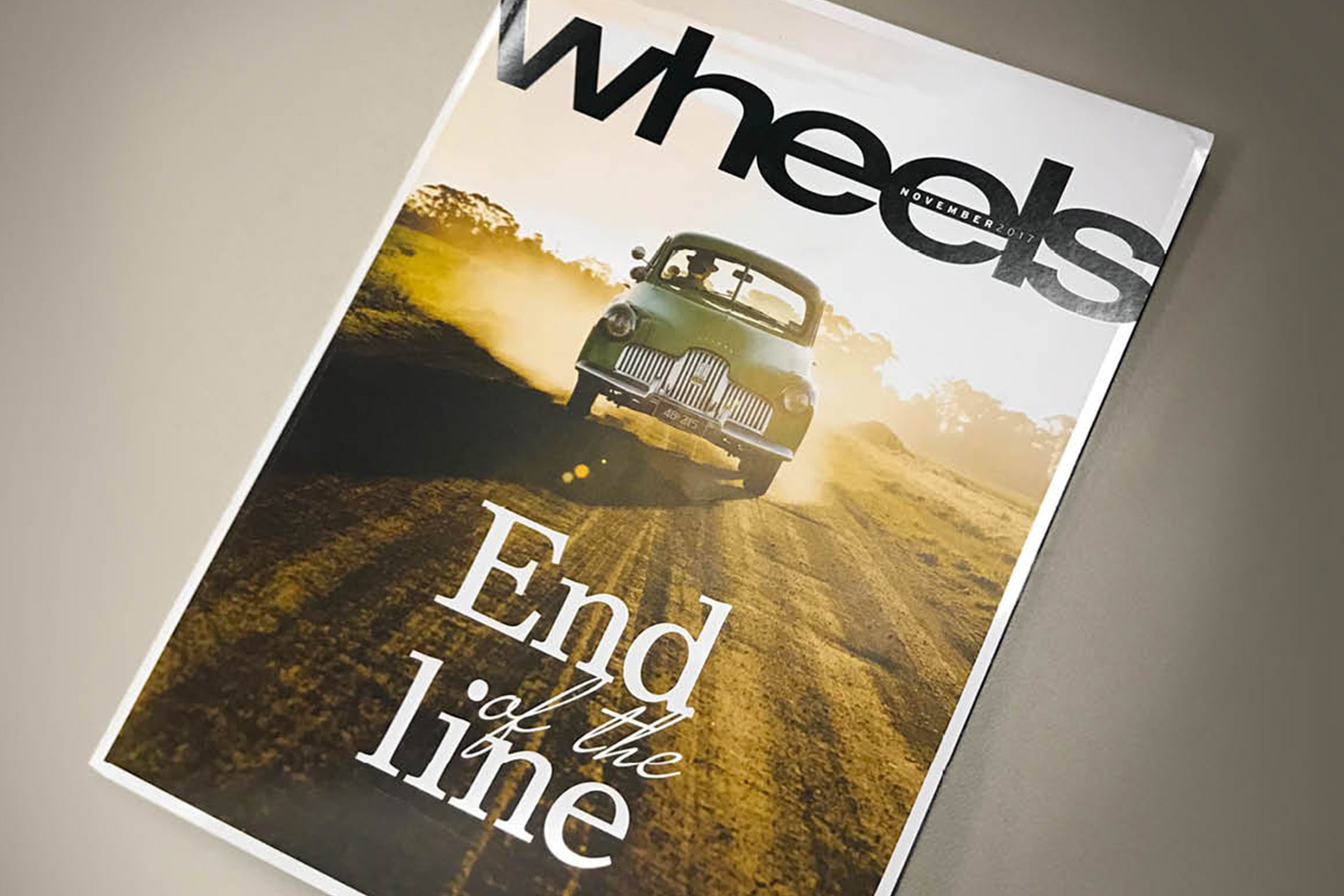

In the United States it was the Model T, in Germany, the Volkswagen. Our ‘People’s Car’ was a humpy hybrid with six-cylinder torque and four-cylinder economy, right-sized for the time and tougher than a stockman’s saddle. Australia’s Own, they called it; proud that 92 percent of it was made here.

A dinky-di Holden was more than a car, it was optimism with a chrome grille, it signalled democracy on the road, new freedom and the prospect of better days.

There was the stirring drumbeat of the greater good, for sure, but also a rich dividend in store for ‘the average man’ in the form of new jobs, new skills and the wealth that went with them.

To the pop of flashbulbs, Prime Minister Chifley posed for his iconic shot with the 48-215, the first Australian car, declaring, “She’s a beauty” to an eager press.

The papers all ran it on page one with the kicker that buyers wouldn’t need a permit, just the 742 quid which was a slug equivalent to two years’ wages. They’d still have to deal with fuel rationing, meaning a maximum of 800 miles driving a year.

Only one in four families owned a car; the Pacific Highway between Sydney and Brisbane was gravel in many parts, with single-lane bridges. A home telephone was the height of modernity.

In his speech, to the 1100 invited VIPs, Chifley was expansive. Prophetically, he described his job as “a man killer”. It was a year before his epic ‘Light on the Hill’ monologue but the pain of war, a shared vision and a sense of common purpose, these were all writ large.

“During the war it was driven home to the government the urgent need of this country being able to produce the things it wanted, not only from an economic point of view but of defence…” he said.

That was sugarcoating it. Early in the war, the Secondary Industries Commission discovered it had little to work with and Australia, being an island continent, was uniquely exposed to a maritime blockade. If it didn’t arrive by ship, it probably wasn’t going to arrive at all.

In 1939, Australia could feed itself but manufacturing anything requiring precision or heavyweight engineering was a stretch. The country needed a manufacturing base. The war effort established a strong platform but Chifley, in his role as Minister for Post War Reconstruction, took a longer view. His words ring down through the decades: “I came to an understanding with General Motors-Holden’s that they would engage on what, for a country of this size, is a very gigantic venture,” Chifley told the Day One audience at Fishermans Bend.

“We had two things in mind – the great development of this country which I think is inevitable … with magnificent opportunities … perhaps in my time but certainly in the time of younger members of the audience, for better standards of living…”

Then the invited throng adjourned to celebrate. They took home a gift of true luxury at a time of boiled wool sweaters and cuts of mutton: a gleaming tin of 200 Benson & Hedges cigarettes.

The scene may as well have been Paris or Monaco for the veterans housed in their euphemistically named ‘pavilions’ at Concord Repatriation Hospital in Sydney.

These drafty wooden huts housed young men for whom the war wasn’t really over. My father spent 18 months there; struck down by tuberculosis acquired in Moratai or Balikpapan, a disease that gradually whittled the strapping six-footer to a form so skinny his shocked mates back in Ganmain reckoned “he’d fit in a matchbox.”

Several times the doctors told him it would be wise to get his affairs in order. But after some close calls he rallied, although his lungs were scarred for life.

He tired of the leatherwork and pottery classes, so started a correspondence course in accountancy.

They told him he was TPI – Totally, Permanently Incapacitated – and offered him a pension with the prospect of one day, perhaps, driving a lift in a department store. History doesn’t record what he told them but “pig’s arse” would have been close.

With two little kids he wasn’t going to pay the bills with a pension. He put his tank driving skills to work on Sydney’s buses, studying when he wasn’t double-shuffling Leyland double-deckers.

The idea of owning a car was beyond his bus driver’s pay packet but the dream was not. And his journey with Holden, like so many others of his generation, is instructive.

My parents didn’t own a refrigerator until the early 1950s. Cooling came courtesy of the iceman, who slipped giant blocks into a chest cabinet.

After my father earned his accountancy qualifications, things looked up for the young family. By the early 1950s, a clapped- out Vauxhall Velox was acquired, which dad rebuilt from valve stem to stern, including new Duco, at night, after work.

What he really wanted was a Holden. But so did everyone else. Despite a looming recession, Holden held 52,000 unfulfilled back orders by March 1950 as petrol rationing ended. That was two and half times the annual production rate, which spiked after early industrial relations setbacks and a crippling coal strike.

The advertising stressed that a Holden was “worth waiting for.”

While it hadn’t been all golden for Holden, by the beginning of the new decade sales of the lion badge were up 60 percent over 1949 and every one of them was Australian Made, an achievement tinged with patriotism and pride for the Greatest Generation.

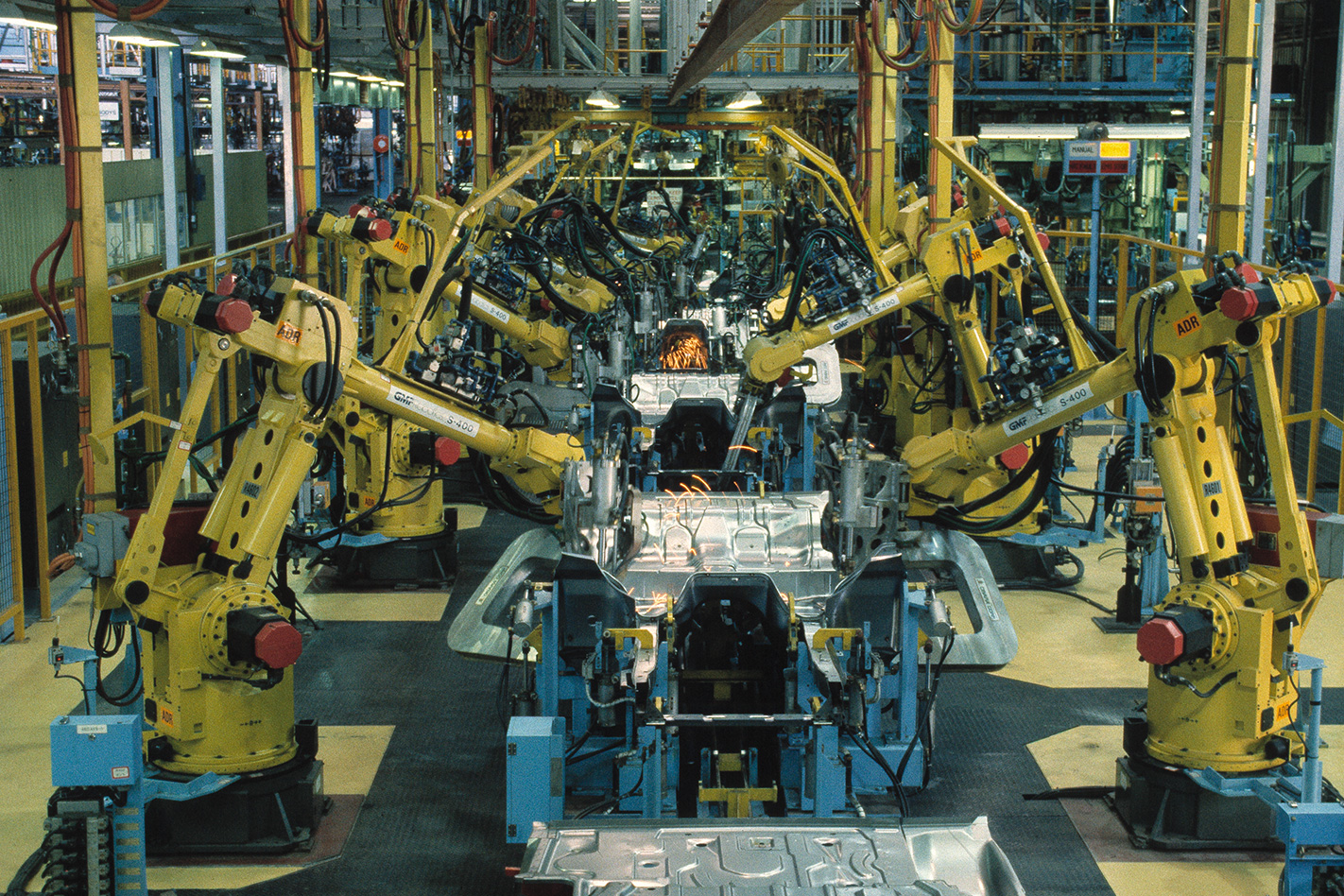

The Holden plants were now churning out 100 cars a day. Profits soared with a margin of 7.4 percent on sales, a car-making record that drew serious attention from Ford’s US headquarters.

With four kids by now, the creaky Vauxhall with the suicide front doors carried the tribe off to Albury in 1957, where the old man was to be a teacher of accountancy with Tech, or TAFE as it became later.

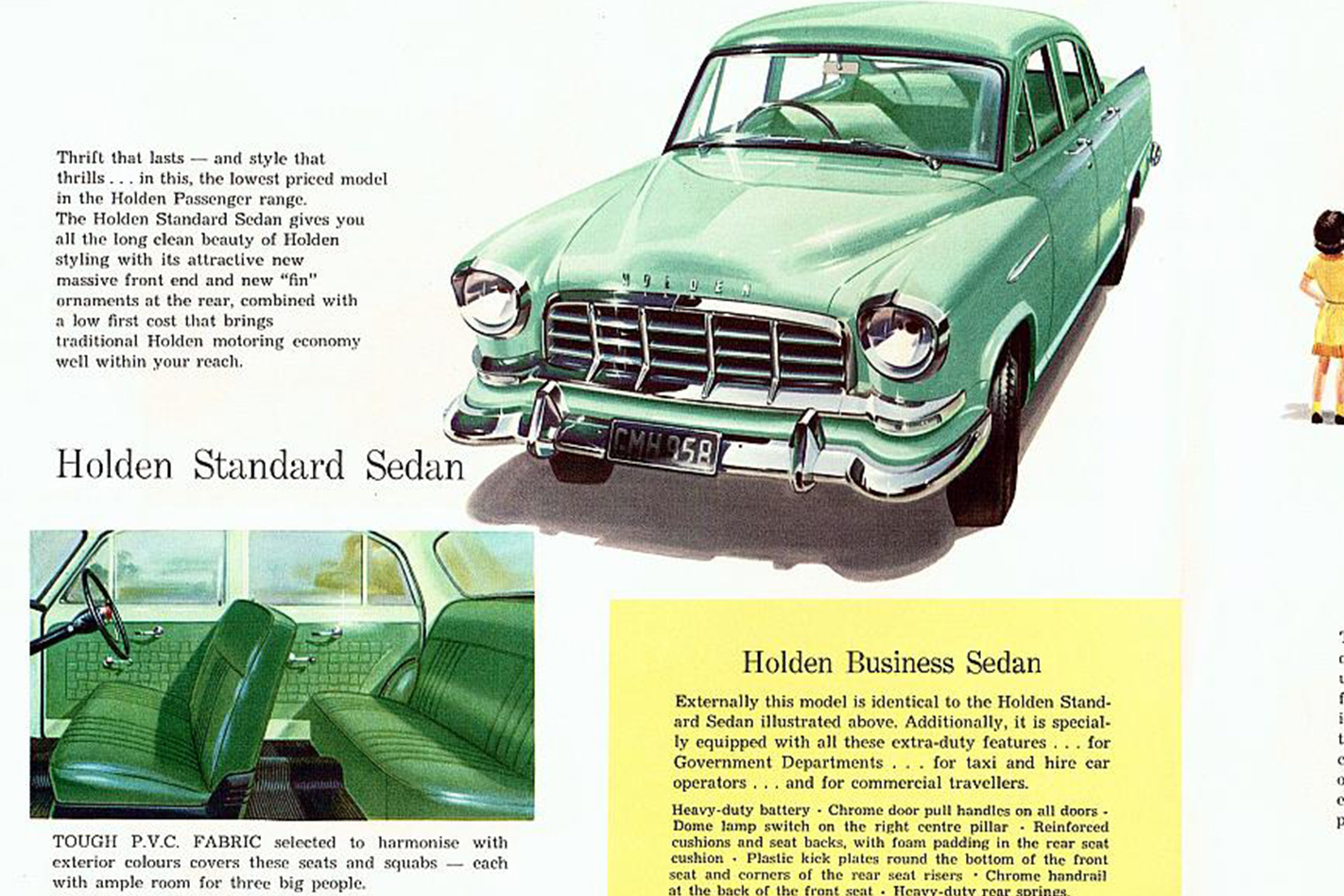

Holden was coining it with production hitting a cumulative 250,000. The 48-215 (retrospectively dubbed FX) gave way to the FJ and the impossibly futuristic FE in 1956, as the suburbs exploded into quarter-acre blocks faster than the dunny man could run, balancing cans of ‘night soil’ on his shoulders. ‘Shitcan’ had entered the Australian idiom. Shitbox, a term widely adopted by motoring enthusiasts, described the location of the can, some of which were equipped with real toilet paper. Many, however, were pioneering recyclers of printed matter.

Just as Chifley and his contemporaries had envisaged, Australia’s Own had spawned a component parts industry, cascading the jobs and wealth to 4000 makers of glass, springs, tyres, instruments and trim.

The FC now had 98 percent local content, but Ben Chifley didn’t get to see it, nor Holden’s achievement of a half share of all new car registrations across its model range.He died from a heart attack in Canberra, aged 66, in 1951. Nation building had proven him right. It really was a man killer.

With five kids now under one roof, my Totally Permanently Incapacitated father set about expanding our Albury accommodation. He did this by hand, making 9000 concrete bricks in the backyard, three at a time, while the radio carried news of astronauts Yuri Gagarin and John Glenn.

Light relief was lopping the head off a chook, followed by plucking ahead of a Sunday roast, accompanied by a long neck of Reschs DA. For so many veterans, this was La Dolce Vita, Australian style. Our green and white FC station sedan with the Savell Brothers Hurstville sticker on the rear screen arrived about the same time as the first Datsuns came off the boat.

This was a momentous day in family history, even if the FC was a secondhand unit with a habit of oiling the plugs. DIY was the default option and secondhand made sense when it came to cars. Dad the accountant knew all about depreciation, but like so many of his contemporaries, he’d worked out the more metal for the money story and the lure of cheap and plentiful spare parts.

Used-car demand underpinned Holden’s business model for nearly three decades, as mums and dads snapped up the ex-fleet and ex-government cars, putting a firm floor under resale values.

Holden market share soared to an all-time high of 45.5 percent in 1958. Combined with stablemate GM models, the company achieved better than half new-car registrations.

The arrival of the EH in 1963 marked Peak Holden, statistically at least, for a single model. It also marked the passing of Peak Hat – at least for blokes not playing detectives on the TV. In the 1950s and early-60s, the wearing of brimmed fedoras and Trilbys was a real consideration for interior headroom. Holden even made a short film about it, trotting out a Perspex cut-out of “the average man” with hat.

At no time, before or since, has a single model line accounted for nearly 40 percent of Australian car sales, but the EH achieved it, just as another Japanese invasion, this one more stealthy and a lot more successful, was beginning.

Australia was about to be given greater choice, more supply and better value for money, none of which mattered to many veterans of the war with Japan. Bill Bourke, the firebrand boss of Ford Australia, captured the spirit of the time with his quote about “no Japanese cars in RSL car parks.”

And so it was, that the Scott family’s FC gave way to the mighty HK, resplendent in white with a gold roof and maroon interior, red motor, three on the tree, non-synchro first, and servo-assisted brakes with all the feel of an on/off switch. It was an ex- Woolworths fleet car; the closest thing my old man had owned to a new one, and had enough grunt to tow our new Viscount caravan. These were salad days for him and for Holden.

Young fellas were strapping surfboards to old Station Sedans (a.k.a. wagons); farmers weren’t fair dinkum unless they drove to town in a Holden ute, and in the big smoke, Life Was Suddenly Very Monaro. Go-go dancers, The Pill, bright paint and GT stripes brought the 1960s to a close with back-to-back wins at the holiest of holies, Bathurst, over the arch enemy at Ford.

As a child of the Depression, one who lived through years of petrol rationing, my old man thought motor racing was “a waste of bloody good fuel” but the halo it cast would define the 1970s and weld Holden’s appeal to a new generation of white, working class Aussies.

The Monaro was the antithesis of Holden’s roots – immodest, flashy, fast and dangerous – qualities the Greatest Generation rejected even as their kids lapped up its hedonism.

“Get one before you’re too old to understand” said the advertising tagline.

Schoolboys could quote the tyre spec, not just horsepower and top speed. Such was its resonance that those same kids, flushed with nostalgia, now middle-aged and cashed up, bought the Monaro encore story in 2001. Never mind the blood-pressure meds, these Boomers were reliving the dream.

Conveniently overlooked was that the original Munro, like most Holdens of the early 1970s, handled indifferently and was under braked.

Guided by American chief engineer George Roberts, early Kingswoods wafted and ploughed around the suburbs, the steering wheel a handy volume control for tyre squeal and scrubbing understeer. No matter, you could order a set of rear-window venetian blinds from the Nasco catalogue.

Holden had become lazy, fat and comfortable.

The character of Ted Bullpit, from the hit TV series Kingswood Country, was a pin-up boy for the era. He was a caricature older bloke, slightly bewildered by a country that was changing around him, tight with a quid, confused about multi-culturalism with his “wog” son-in-law, but passionately wedded to his Holden Kingswood.

There were plenty like Ted who remembered the war years; the virtues of being frugal and never pushing your own barrow. But the demographic conveyor belt was spitting out kids with no memories of real hardship. This was the ‘Me Generation’ and it took the piss out of institutions. The RSL was a particular target as Canberra reintroduced conscription and sent 20-year-olds off to a hot war in Vietnam.

White Australia was still government policy until 1973 and cutting the rust out at rego time an annual ritual.

Who gets rust today? And nobody gets conscripted.

My father didn’t exactly re-chrome the tow ball when his HZ Radial Tuned Suspension Kingy arrived, with its 4.2 V8, but his handwritten logbook recorded every drop of oil, every fluctuation in tyre pressure and every bit replaced at service time.

It was a thing of beauty and a real joy for him. Aussies built good cars, there was a mining boom on and all was well with his world. None of his sons had yet had their birthdate drawn from the barrel that led to Kapooka for conscript training.

He kept quiet on anything to do with armed conflict. Not once did he march on Anzac Day and the only glimpse he allowed was a one-liner, years later, while savouring a beer late one afternoon. I asked him about Borneo.

“Bad business…” he muttered. “Flamethrowers … bad business…” Then he changed the subject.

At starched-collar Holden, the surf boom Sandman – a savvy recognition of real-world customers – was a product of a sales and marketing team with more chutzpah than the engineers.

Puberty Blues was the book and the movie; shagging and surfing the plot lines. Converting panel vans and wagons to beachside bed-sits was nothing new but this was the first time a major manufacturer had acknowledged the trend by turning a panel van into an off-the-shelf ‘lifestyle’ vehicle.

Football, Meatpies, Kangaroos and Holden cars arrived on TV screens in 1976 courtesy of George Patterson advertising. It was Aussie nationalism writ large; a celebration of egalitarian values. It traded shamelessly on patriotic pride and started something of an Ocker genre on the telly.

Except it was all American, just like the Channel Nine news theme from CBS. The jingle was originally conceived as ‘Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie and Chevrolet’ and it wouldn’t be the last straight lift. In the 1980s, ‘We Build Excitement’ was a Pontiac tag line nicked by Holden Special Vehicles.

Both are subtle but symptomatic hints that maybe Holden was not quite as advertised. On paper, it was never Australia’s Own. Not a single share existed in local hands since the late 1950s, when the Holden family sold their small tranche of preference stock. The company lauded by Chifley and adored by the post-war generation has always been a wholly owned subsidiary of General Motors.

For all its resourceful local engineers, talented designers and gifted sales and marketing executives, Holden took its orders and nearly all its fly-in, fly-out managing directors from corporate HQ. They tended to keep their heads down when interacting with government, playing the role of house guests, with one or two exceptions.

General Motors in Detroit was a hierarchical culture very foreign to blunt-speaking Australians but every now and again it threw up a kindred spirit.

Charles ‘Chuck’ Chapman arrived in 1976, a Marine veteran who fought at Iwo Jima then put himself through night school. A practical engineer with a global view, he arrived via Opel in Germany and inherited a mess not of his making, a company insecure and indecisive in a rapidly changing social and economic environment.

The Commodore, a re-engineered Opel, was his baby and a seemingly good bet at a time of a global fuel crisis as queues formed outside petrol stations.

He had a big go at boosting exports to claw some economies of scale, selling four- cylinder engines to Korea and Europe. It went well for a while but the rest, as they say, is history.

Chapman and his team did a mighty job but by the mid 1980s he knew the Holden business was in serious jeopardy.

The government’s 1984 blueprint for the motor industry was called The Button Plan, named after its author. Its message was pretty clear. Australia had too many carmakers producing too many models to be efficient, all of them sheltering under stiff import taxes and quotas that restricted competition and inflated prices. Get efficient or get out was the bottom line.

Shock followed as leaked Holden board papers of the time hit the newspapers. They recommended a merger with Nissan as a viable option.

My father read that story in total disbelief. When the VL Commodore arrived with its Nissan six-cylinder engine, Dad rationalised buying one as being good for jobs and supporting local industry. He also quite liked the zing of the engine and conceded the Japanese were good engineers. But his heart wasn’t in it anymore, despite his often-repeated, “this one will see me out.”

BACK in the mid-80s, sitting in the hallowed boardroom at General Motors in Detroit, I had the chance to interview Roger B. Smith, the chairman. It was an epiphany. As he prattled on about building a paperless corporation and how the new brand Saturn was going to conquer the world, he seemed genuinely clueless about the world outside Michigan. His face flushed red under serious questioning about America’s market-share losses to Japan both at home and abroad. He got testier by the minute to the point his minders stepped in. Here was a dull corporation man, uninspiring and scarily uninformed, running the biggest carmaker in the world.

Down the road at Ford and some little time later, the boss was Red Poling. He answered my question by declaring the best car in the world to be the Lincoln Town Car.

General Motors Corporation went into Chapter 11 – unthinkable but true – during the 2008-09 financial crisis and had to be bailed out by the US Government.

It emerged from bankruptcy with a new chief executive, Mary Barra, who immediately made a break with history.

The announcement came in December 2013: Holden would no longer make cars in Australia.

My father didn’t quite live to see it, passing away just eight weeks earlier, aged 94.

In many ways we are back to the 1939 of his youth. Australia is an island without a heavy manufacturing industry. The globalists say this is okay; it’s the market at work and there’s nothing to worry about. In 100 years, warfare has moved from sabre to cyber, so all this blockade stuff, all these arguments about self-sufficiency, are outmoded.

Meanwhile, in the South China Sea, ‘freedom of navigation’ exercises continue.