Attempting to name the 10 most significant people in the Falcon’s 56-year history is an almost impossible task.

This article was originally published in the November 2016 edition of Wheels, and is being republished on the fourth anniversary of Ford Australia ceasing manufacturing in Australia.

After talking to ex-Ford executives and colleagues, and reading everything I could on Ford Australia, I came up with a working list of 35 names.

Compressing that into just 10 proved hugely challenging, the order constantly changing.

One name stood above all others, however: Bill Bourke. The charismatic Bourke took on Holden, knowing it would take well over a decade of dedicated work across every aspect of his company to grab sales leadership.

He created an environment that made young graduates, whether from engineering or finance, want to work for Ford. He understood product and knew how to create a strong public awareness for his company and its cars.

The other names span the Falcon story, like Charlie Smith, who made the brave decision to drop the Zephyr in favour of the new Falcon, and finishing with Bill Ford, who (with Alan Mulally) killed any chance of the Falcon becoming a global car.

In between you’ll find a designer, manufacturing genius, salesmen and engineers, all of whom devoted most, if not all, of their careers to Ford and the Falcon.

10. Bill Dix

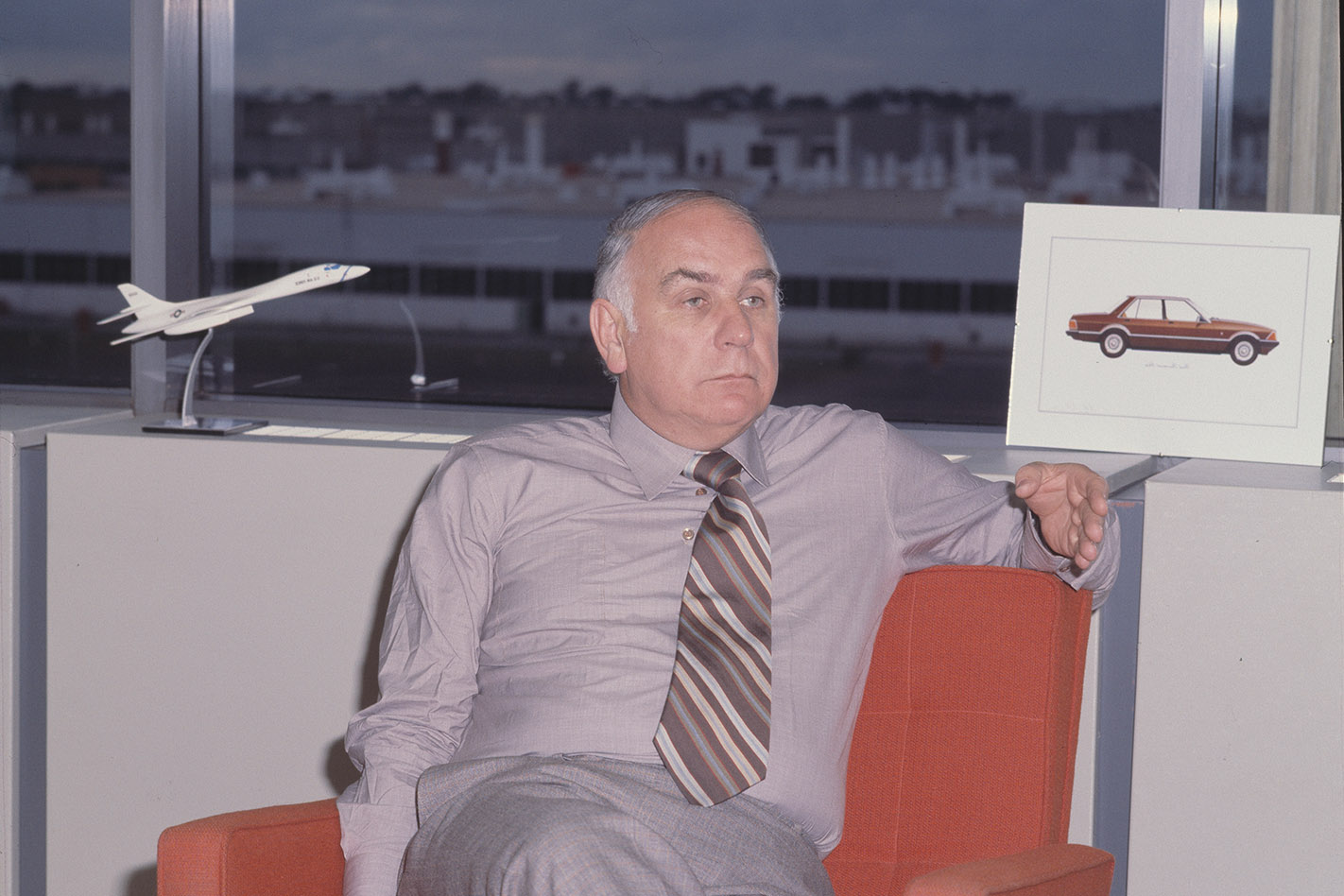

The CEO who saved Falcon by canning the misguided Capricorn Project

Bill Dix, Ford Australia CEO from 1981 to 1990, is best remembered as the man who cancelled the Capricorn program in favour of retaining the Falcon. For two years in the early 1980s, confronting a second energy crisis and Holden’s move to the smaller Commodore, Ford seriously considered replacing the XD-generation Falcon with a stretched, front-drive Telstar/Mazda 626 in both hatchback and sedan forms. The product planners’ idea was to extend the wheelbase by 135mm and overall length by around 225mm, but without adding any width. The inevitable result was a long and skinny car. They struggled with the project, spending valuable engineering and design resources on what, hindsight tells us, was a crazy project.

Local content demands meant building the Capricorn’s four-cylinder engine in Geelong (thus forcing the end of V8 assembly). Gradually, Ford realised that with continuous engineering improvements, the Falcon used less fuel than the rival Holden. To his great credit it was Dix, as the new CEO, who cancelled the Capricorn program. However, Capricorn’s impact on future Falcons was immense. There was nothing in the pipeline beyond XE. The planners realised they needed an interim facelift (XF) while rushing to pull together the program that became EA.

Remember when: 1979

In 1979, after Ford took a 25 percent holding in Mazda, Dix became president of Ford of Japan and played a key role in creating a solid working relationship between Ford and Mazda that lead to joint product development, most effectively with the Laser.

9. Bill Ford

Henry Ford’s great grandson, and wielder of the Falcon axe

The moment Bill Ford cancelled Ford’s all-new rear-drive program in 2005, just months away from committing to tooling, any chance that the Falcon would survive was gone. The new Panther platform, created to replace the aging American Ford Crown Victoria, Lincoln Town Car and Mercury Marquis, also included truly new (and Australian-designed) Falcon and Fairlane, and a raft of speciality models including a new Lincoln LS and Continental, Ford 427/Interceptor, a Ranchero (the American name for Ford’s Ute) and, they anticipated, the new Mustang.

As Ford sunk further into financial trouble, Bill Ford, then CEO and Chairman, decided they couldn’t afford the new program and concentrated instead on reworking old Mazda and Volvo front-drive platforms for a new Taurus and, in Australia, yet another reskin of the Falcon.

Then new boss Alan Mulally, who succeeded Bill Ford late in 2006, came up with the One Ford product development philosophy and the era of creating new models for individual markets was over. If the Falcon (and Territory) couldn’t be included as global models – not helped by Dearborn’s insistence that Broadmeadows build the Falcon in right-hand drive only – they had no chance of surviving.

Remember when: 1999

In February 1999, when an explosion ripped through Ford’s River Rouge plant in Michigan, killing six employees, Bill Ford rejected his advisors and rushed to the scene. One reputedly told him, “Generals don’t go out on the front lines”. Bill replied, “Then bust me to private.”

8. Trevor Worthington

Father of the BA, who also really managed to stamp out his Territory

As engineering father of the BA Falcon, Trevor Worthington, now Vice President of product development for Ford’s Asia-Pacific operations, deserves credit for the Falcon surviving into its sixth decade.

The Benalla-born (Vic) engineer understood that, after the disappointment of the AU, the Falcon demanded a major lift in refinement and appeal to lift sales to a sustainable level. The traditional Australian front-engine/rear-drive formula remained, but BA combined that with greater sophistication and a more-worldly attitude. Driven in large part by Worthington, Ford’s local engine engineers developed a new dohc, 24-valve cylinder head for the 4.0-litre straight six that amazingly still traced its origins back to the original Falcon’s 2.3-litre ohv engine.

From the time he joined Ford Australia in 1985, Worthington worked in product development – meaning Falcon, Falcon, Falcon – and product strategy, before leading product development for six years during the era when Ford crafted the Territory, using the BA as its baseline, and the FG Falcon reskin. Ford never had the money to do a clean-sheet car in Australia, yet today’s Falcon, overseen by Worthington from his new base in China, is a tribute to the company’s cleverness and diligence in doing so much with so little in terms of improved safety, performance, handling and comfort.

Remember when: 2015

Talking of the end of the Falcon, Worthington told journalists, “I’m personally disappointed, but every cent we spent on Falcon and Territory – and when we spent it – were the right decisions and I wouldn’t have changed a thing.”

7. David Ford

Talented engineer with vision for the space around Falcon

David Ford (no relation), who started at Ford Australia in 1964 as a product planner, was on assignment in Europe when, in 1968, he was told to get over to Dearborn to work with the designers on the XA Falcon.

That was the real start for Ford, who rose to become chief engineer and was directly involved with generations of Falcons (plus Fairlane and LTD) until he left Ford Australia in 1990 to spend the next eight years in senior product roles in Dearborn.

It was Ford who convinced Bill Bourke, who wanted an upmarket model above the Fairlane, that rather than do a local ‘Thunderbird’ based on the Falcon Hardtop, they should stretch the Fairlane to create the LTD. In the end Bourke agreed, but insisted they do both.

In the late ’70s, knowing Ford desperately needed to reduce the Falcon’s fuel consumption, David Ford decided they need an alloy head which promised a 10 percent improvement. Ford went to Japan searching for a supplier and finally reached an agreement with Honda to supply the new head for the 1980 XD Falcon. The policy of constant improvement also saw him responsible for the XE’s Watts-link rear suspension.

Remember when: 1967

David Ford can rightly claim a major role in conceiving the ZA Fairlane, the hugely successful, locally conceived development of the Falcon that took Holden totally by surprise. The rival Statesman didn’t arrive for four and half years.

6. Keith Horner

Put a broom through the dealer network, helping Falcon to a clean sweep

After Keith Horner introduced new Ford Australia managing director Wally Booth to the NSW Ford dealers in 1963, he closed the door to the conference room and told his boss, “The best thing we could do for the Ford Motor Company is throw some hand grenades into that room and lock the doors.”

Irascible, hard-nosed and utterly determined, Keith Horner knew that nationally Ford’s dealers were tired, old and complacent; many were now public companies run by managers. As national sales manager and later marketing and sales director, Horner set out to transform the dealer body.

Read next:

In the mid-1960s, with Ford beginning the Falcon’s fight back to respectability, Horner set up a process that enabled young men with as little as $20,000 to become Ford dealers. If they mortgaged their homes and, thus, were totally committed, Ford would finance the rest. Do that, work hard, and most quickly became multi-millionaires.

The new dealerships enabled Ford to sell the volumes necessary to eventually beat Holden. Horner managed the dealers like nobody else, before or since. His voice was strong on every decision within the company. Horner trained Max Gransden, his successful successor, but Gransden wasn’t as effective or as visionary as tough old Keith.

Remember when: 1973

Horner hated the press. At the launch of the LTD/Landau, I tried the coupe’s rear seat, only for the front seat back to fall off. I handed the piece to Keith. His response: “If you’re so bloody clever, you’d be earning twice as much as a product planner.”

5. Brian Inglis

Manufacturing guru who would later lead Ford Australia through the glory years

Spitfire pilot during WW2, and later the first Australian to head Ford Australia, Brian Inglis was with Charlie Smith in Dearborn when they decided to can the Zephyr and go with the new Falcon. As manufacturing director, Inglis was then responsible for retooling for the new model, Geelong’s new stamping and engine plant, and the Falcon’s final assembly in the greenfield Broadmeadows factory, a staggering achievement.

He was managing director and CEO of Ford Australia through the Falcon’s glory years of 1970 to 1981 and remained chairman when promoted to run Ford Asia-Pacific. He continued to be a huge supporter of the Falcon and understood its importance in manufacturing employment in Geelong and Melbourne.

Inglis loved to visit the Broadmeadows design studio over the weekend to watch the clay modellers at work. With a fine eye for design, he championed the late move to an ultra-low waistline for the XD. He was also a great supporter of Ford’s excellent graduate program that fed the company’s executive pool with a stream of young, enthusiastic men who later provided management at the highest levels of FoMoCo.

Remember when: 1977

Sir Brian Inglis was knighted for services to industry in 1977. Along with four other Australian pilots, he was also awarded the Legion of Honour, France’s greatest decoration, in recognition of their role in liberating France.

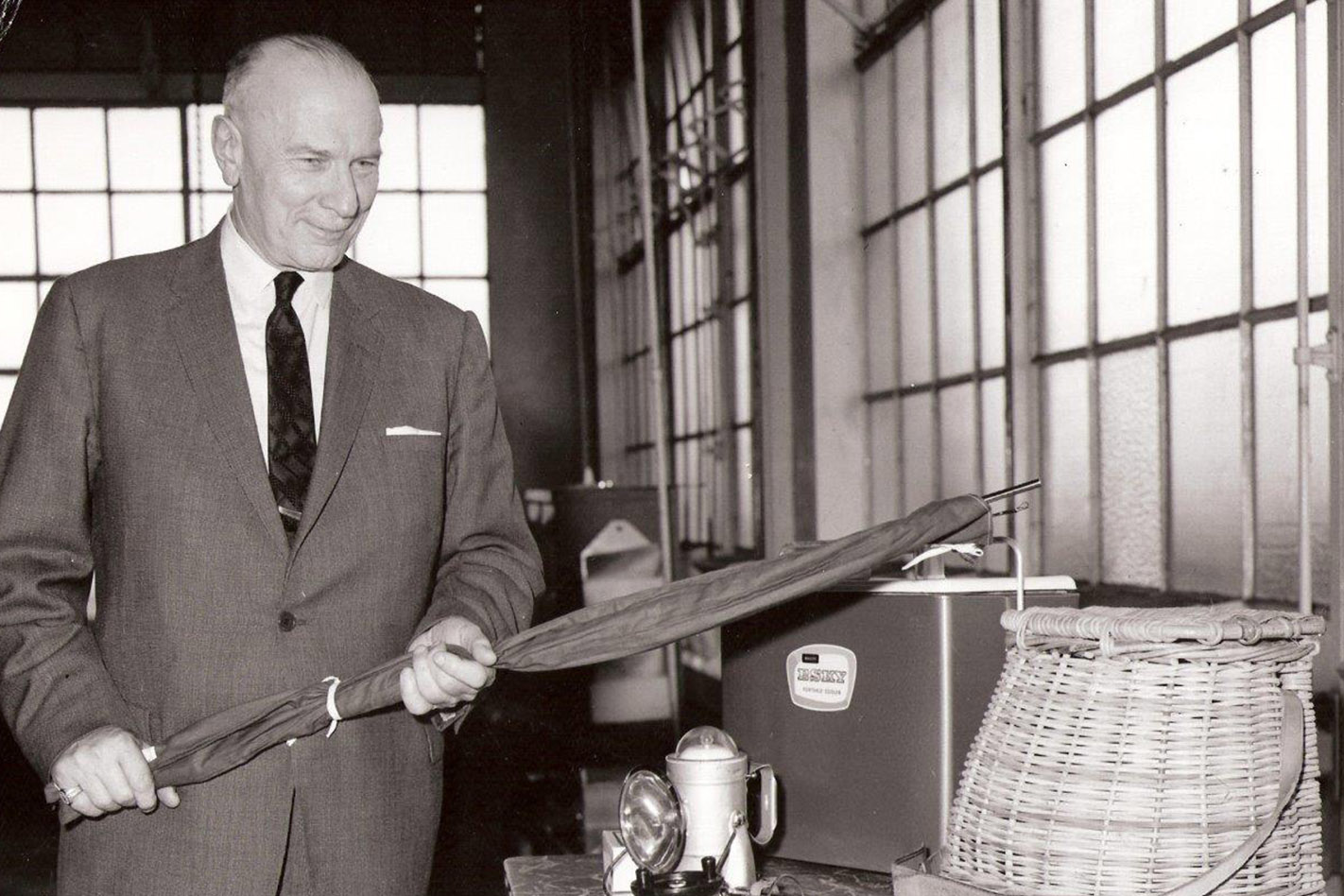

4. Charles Smith

Drop-kicked Zephyr with a ‘return to sender’ note. Enter Falcon.

Charlie Smith will always be remembered as the Ford Australia MD who, disappointed by Dearborn’s restyle of the English Zephyr Mk II, sent the famous telegram to Ford in Geelong, “Cancel Zephyr”.

The story may be Ford folklore, but the result was the same. Ford committed to the Zephyr in February 1957, tooling was underway and the program approved by the Federal Government, so it took a brave man to tell the Americans, upon seeing a Falcon design proposal, “That’s the car I want for Australia”.

The Falcon was modern, cheaper to build and lighter, though Brian Inglis, one of the Australians who rejected the Zephyr in 1958, later admitted, “The Falcon was not as robust as our restyled Zephyr and we certainly had our misgivings.”

English-born Charles Smith joined Ford in 1922 and became Australian MD in 1950. As the locally-manufactured Holden took sales leadership he watched Ford’s market share slide below 10 percent. Smith later remembered, “We introduced the Consul and Zephyr, but that wasn’t good enough; we had to find a product we could manufacture if we were to remain a major force in Australia.”

That meant a new plant. Smith, encouraged by the Victoria premier, bought 182 hectares (450 acres) at Campbellfield at £500 an acre. The plant would produce cars from August 1959 to October 2016.

Remember when: 1950

Charlie Smith’s first task as boss of Ford Australia was installing a V8 assembly line in Geelong. But it was getting head office (then Ford of Canada) to agree to spend $40m on manufacturing a car here that set the scene for the Falcon.

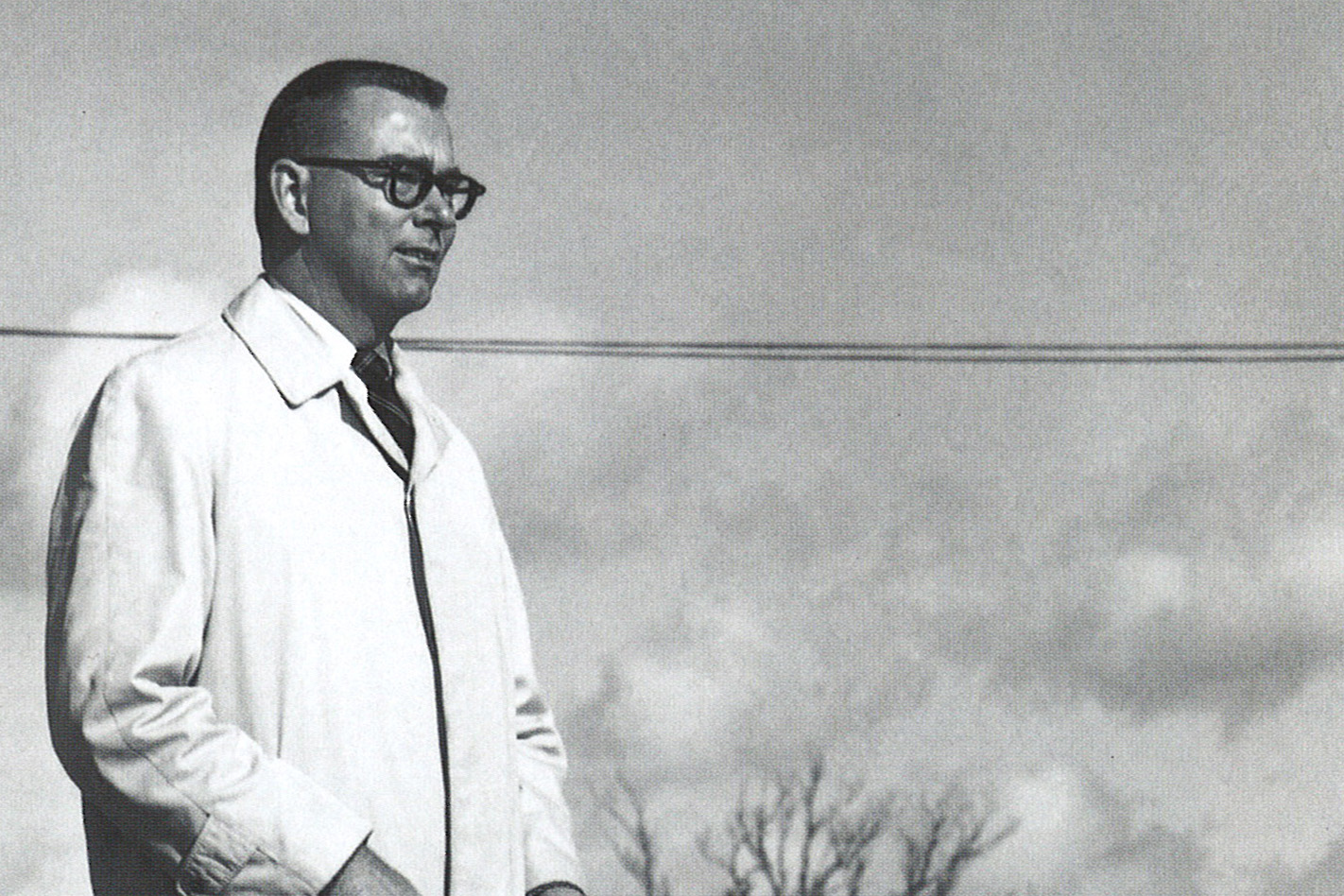

3. Wally Booth

Numbers man who made early Falcons really start to add up

Everybody remembers Bill Bourke, but few appreciate the key role played by his predecessor, Wallace ‘Wally’ Booth. The crew-cut, 40-year-old Booth was sent to Australia in 1963 to fix Ford Australia or shut it down (sounds familiar; this scenario was to be repeated by new CEOs on at least three separate occasions later in the Falcon’s life).

Brian Inglis remembered Booth “as a finance man with imagination”, a rare combination. Booth was extraordinarily well connected in Dearborn – he had the ear of Ford’s legendary beancounter R.J. Miller – and was a man who made things happen. It was he who employed Bourke.

In True Blue, Bill Tuckey’s book on 75 Years of Ford Australia, he writes, “Inglis said Booth saw the fundamental problems of Ford Australia and set out to get the manufacturing systems right, create a product engineering base, set up a new sales operation and dealer body, and discipline the component suppliers.”

Booth also knew he had to get the Falcon right, and approved a plan to use South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula as a proving ground (pre-You Yangs). Based at Port Lincoln, the engineers belted Falcons until they dropped, leading to 1500 engineering modifications, mostly to make the car tougher. Booth even agreed to use Port Lincoln for the XM’s press launch.

Remember when: 1967

Ford couldn’t decide between Fairlane, Monarch and Pacific for the name of its new luxury car, then under development for launch in 1967. Chief engineer Jack Prendercast wanted Fairlane S-C for Southern Cross. It was Booth who choose Fairlane.

2. Jack Telnack

Led the design of the first true, all-Australian Falcon

“Go down there and do something; just don’t make my telephone ring.” Jack Telnack was 29 years old when Gene Bordinat, vice-president of Ford design, sent him to Australia with that simple instruction.

He arrived in October 1966, just weeks after the launch of the XR. The talented Telnack’s first job was facelifting the XR to create the XT, working out of “a tiny shoebox of a place” hidden away in Ford’s Geelong facility. Knowing that the American Falcon’s days were numbered, Telnack head-hunted John Doughty, 22, from Holden, and Brian Rossi, 25, from Ford of Europe, and together they did the XW and XY, while realising that if the Falcon was to survive, an all-Australian car would be required.

The XA, the first Australian-designed and engineered Falcon, was styled by this trio of whiz kids in Dearborn, with MD Bill Bourke flying the Pacific every two weeks to check on their progress. Finally, Bourke was told to create his own studio in Broadmeadows. Telnack set up and ran the new design studio until he was promoted to head of design in Europe in 1975 and then global design boss in 1980.

Unlike many crayon-pushers, Telnack understood design and engineering, was always supportive of Australia, and any new Falcon program until he retired in 1997.

Remember when: 1985

Telnack is best remembered, not for his work at Ford Australia, but for the breakthrough 1985 aerodynamic Taurus that quickly became America’s best-selling car. The Taurus was seen as responsible for bringing European design influences to Detroit.

1. Bill Bourke

Energetic visionary who helped reshape our perception of Falcon

When MD Wally Booth went looking for a super-salesmen to help Ford recover from the Falcon’s durability woes, Dearborn sent him William Oliver ‘Bill’ Bourke, 37. History proves this was an inspired choice.

It was the charismatic Bourke who came up with the 70,000-mile You Yangs durability run to help convince the public that the XP Falcon really was new and durable; the flamboyant Bourke who, after driving an XR police pursuit car, decided to produce it as the bronze GT; Bourke, the product guy, who agreed to the Fairlane and LTD (and Landau) strategies that so traumatised Holden; Bourke, the industrialist, who later, as head of Ford Asia-Pacific, sold Dearborn on Ford Australia’s need to engineer uniquely Australian Falcons; the energetic Bourke, who most of all, set out to (and succeeded) in breaking Holden’s sales domination in Australia.

Twice, Henry Ford II promised him the top job at Ford, but he was shafted by the Dearborn clique for being too candid in his opinion of Ford chairman Philip Caldwell. Ford executives remember Bourke as a visionary, a true leader, and a straight shooter. According to Bob Lutz, Bourke was, “a gifted and charismatic leader.” Indeed.

Remember when: 1969

A regular XW Falcon GT was never good enough for Bourke. It’s legend now that he shipped his XW to Dearborn and had the 351 cubic inch V8 replaced by a 428 Cobra Jet V8, plus upgraded rear axle and transmission. The one-off still exists.

THE HONOUR ROLL

Any list that attempts to compress the Falcon’s 56 years into only 10 people is inevitably going to provoke controversy.

We wanted to include dozens of others, all of whom played significant roles across the Falcon’s epoch, and who rightly deserve mention.

We apologise for those we may have missed. In no particular order these people warrant recognition: Jack Prendercast, Clive Potter, Ivan Tan Sing, Ian Vaughan, Jack Lavers, Jack Kelly, Al Turner, Geoff Polites, Peter Arcadipane, Carl Mueller, John Murray, Trevor Creed, Bob Marshall, Don Pearce, Wayne Draper, Brian Rossi, Jack Hawke, Steve Parke, Alex de Vlugt, Fred Bloom, Russell Christophers, Scott Strong, Allan Moffat, Max Gransden, Lindsay Dawson, Tom Pettigrew, Dave Wilkinson, Peter Gillitzer, and many more.