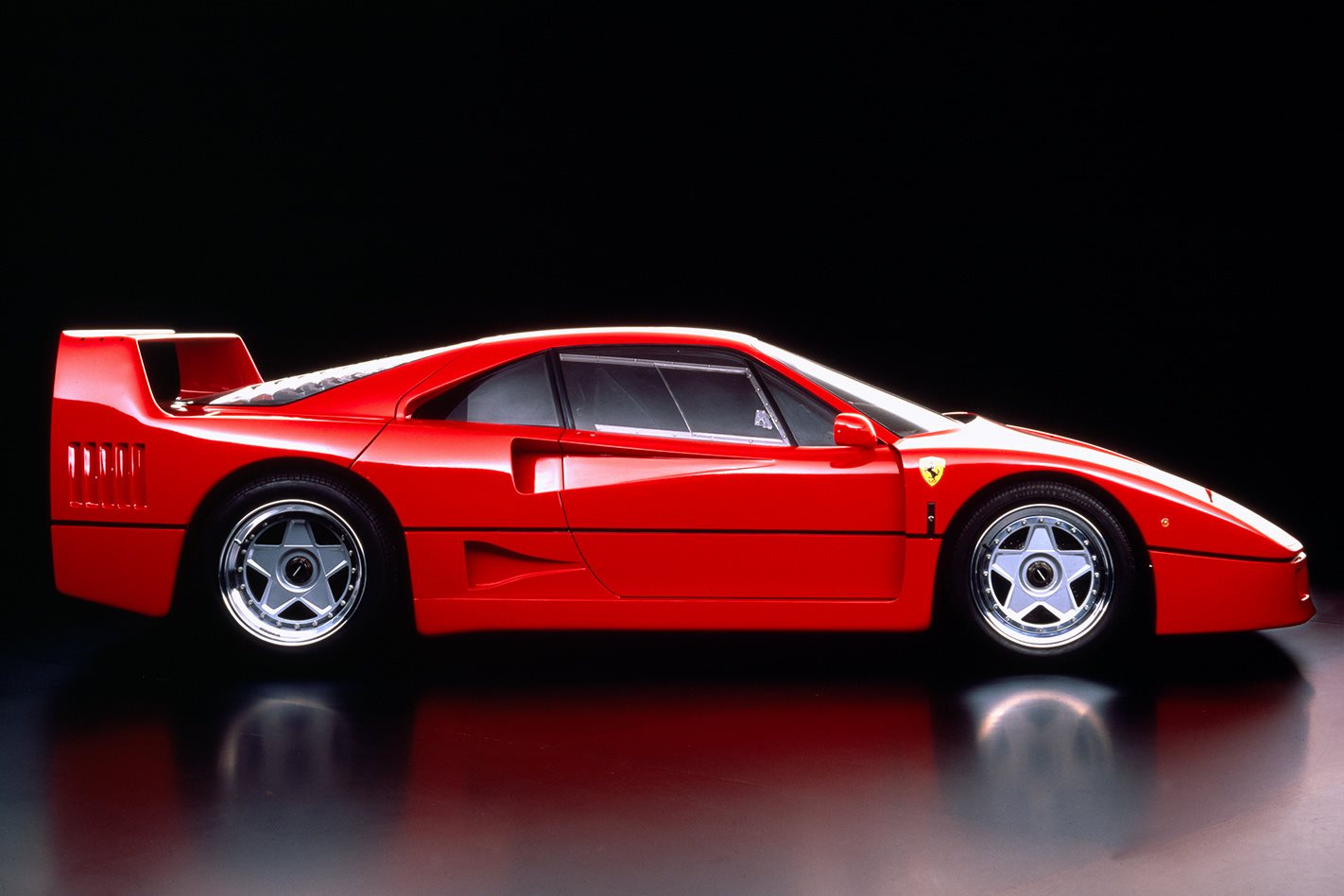

Wheels is saddened to learn of the passing of Nicola Materazzi, father of both the legendary Ferrari F40 and the 288 GTO before it, at the age of 83.

Our thoughts go out to his family and friends. He will be fondly remembered by all Tifosi and motoring enthusiasts around the world.

December, 2019: Wheels talks with the man before the F40 and the 288 GT0

Editor’s note: in honour of our lively chat with Signor Materazzi, the story below is presented in its original, unaltered form.

Have you heard of Nicola Materazzi?

He may well be the most extraordinary Ferrari engineer to have slipped under the media radar, for he is nothing less than the father of Ferrari’s turbocharged engines, but also the man behind legendary cars such as the 288 GTO and F40.

Today he enjoys a busy retirement at his house in the Salerno area south-east of Naples, surrounded by a collection of 12,000 books, 8000 of them car-related. It’s the region Materazzi (below) calls home, having been born in January 1939 in nearby Caselle in Pittari.

“I’ve always loved books ever since I was a teenager,” he says. “They are a source of inspiration. I have read all of these, and in reading them you learn. Learning every day is still the most important aspect of my life.”

From these books came ideas. “The turbo idea came from reading about aircraft engines during the wars and developing it with a book about fuel. This is why, at university, I spent two summers at Mobil’s oil refinery in Naples and spent hours reading books about the detonation issues.

“It’s often overlooked, but the real reason for the British success during the Battle of Britain is linked to the fuel. The creation of tetraethyl lead by an American company led the way to an amazing power increase in the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. From 950bhp with 87-octane fuel before the war, it rose to 2000bhp with fuel of more than 100 octane at the end, while the Germans’ fuel stayed the same…”

Materazzi’s automotive career started at Lancia. The Turin-based company hired him in the early 1970s, after he left his position as a university professor in Naples because of the turmoil of the 1968 student rebellions.

“I was tired of being on the wrong side of the fence,” he remembers. “When I was a student, I had to be very respectful of the teachers. But as soon as I became a teacher myself, the 1968 youth revolution exploded. The power went to the students, totally disrespecting the figure of the professor.”

Materazzi knew it was time to change direction. “I sent a letter to Lancia, asking for a meeting. Cars had been my passion since my earliest years, and they invited me to Turin. They asked me to bring my degree certificate; they liked my approach, but it was so unconventional that they weren’t so sure that I really was a graduate!

“The meeting went well – so well that I missed my train back home, but by the time I was buying another ticket I was a Lancia employee working under Francesco De Virgilio, the designer of Lancia’s V6.” Materazzi had just become the happiest man on earth, but his father, a doctor, was the unhappiest. “He was losing his son, kidnapped by cars, in far-off Turin…

“One of my early successes – the one that opened the door to the racing department and the Stratos project, for which I did the chassis and the suspension – was with the Beta in the rally championship. We had a MacPherson suspension on the front, and the rules said we needed to keep the original mounting.

“I created a top mount with an eccentric hole, so we could modify the camber. We won and were legal, but the FIA changed the rules when they discovered it.”

“I sent a letter to Lancia, asking for a meeting. Cars had been my passion since my earliest years, and they invited me to Turin. They asked me to bring my degree certificate; they liked my approach, but it was so unconventional that they weren’t so sure that I really was a graduate!

The time of the turbocharger was drawing near, although it was by no means a new invention, as the former professor explains. “We tend to think the turbo engine is something relatively recent, but the technology was developed during World War I to help solve the power loss problems in aircraft flying at higher altitude. The first unit was tested in 1916, using a truck driving up Pikes Peak to simulate flying conditions at altitude without risking a pilot’s life.”

The moment came when Swiss racing driver Michael May, a friend of racer and engineer Mike Parkes who had an office next to Materazzi’s at Lancia, revealed during a visit that Porsche was preparing a turbo engine for racing.

“So it was easy to convince everybody that the car I was preparing – our new Group 5 Lancia Stratos ‘silhouette’ – needed a turbocharger,” Materazzi recalls. “More difficult was finding the components. Turbochargers were almost non-existent; the KKK company was still called Eberspächer, and the only three units they had were all for trucks.

“It was easier for Porsche, because they used bigger engines, but I had to adapt. I also needed to understand how far I could push the compression ratio before the turbo boost is added. One of the biggest issues was detonation, because with the turbo you effectively increase the compression ratio to a level where the octane of the fuel makes a big difference. For example, in the Ferrari Formula 1 turbo engine, the real compression ratio was growing from 7.5:1 to 19:1. We started with 380bhp and ended up at more than 500, so we did well.”

Lancia had been bought by Fiat in 1969, but its people did not really show up until 1975. For Materazzi, the first thing they then did was to postpone his promotion to management for three years. “Luckily, though, I was moved to the racing department away from the politics, the cost-cutting and what I call the Fiat managers’ policy of average. I stayed there until they unified the racing departments, and we, from Lancia, ended up in Corso Marche where Abarth had its operation.

“I wanted to leave but Stefano Jacoponi assigned me to the Formula Fiat Abarth project. One evening at dinner, I met Enzo Osella [the racing car manufacturer and later F1 team owner]. He had a wonderful engine for his Fiat 127 with a body by Fissore, but it over-revved in top gear of the four-speed gearbox. I suggested a five-speed unit, and he asked me to design it. It worked, and he sold a lot of cars until Fiat, two years later, offered an exact copy of my unit as standard.”

That rankled with Materazzi, but he was aiming for higher things. ‘With Osella we entered the Formula 2 championship, with a short-stroke engine. We did very well, competing for the championship until the very last race. This, and successes with the BMW M1 Procar, opened the door for us into Formula 1, but I left before that program was revealed to the public.

“That’s when I went to Ferrari, at the end of 1979. It was sad for Osella, but he understood my great opportunity. Enzo Ferrari was looking for someone to manage the Formula 1 technical department and he liked my experience. I told him I didn’t have a great relationship with Fiat’s people, but he reassured me that, being in the racing department, I’d report to him only.”

Materazzi had been at Maranello just three days when Enzo sought him out for urgent help. There was a problem with the new Formula 1 engine, the turbocharged V6 in the 126C, and Enzo knew who would have the answer. “There was an issue which caused the sealing rings in the heads to fail; I had already fixed this when working on the Ferrari V6 for the Lancia Stratos project,” says Materazzi.

“When those test engines were melting their pistons, I discovered that some cylinders were receiving a leaner mix. We solved it by adopting a conical air intake, and later we used the same solution on the F40, along with extra fuel to cool it down. That’s why the F40 runs richer above 5500rpm.

“Enzo Ferrari was looking for someone to manage the Formula 1 technical department and he liked my experience. I told him I didn’t have a great relationship with Fiat’s people, but he reassured me that, being in the racing department, I’d report to him only.”

“These were the months when Renault’s Formula 1 car was nicknamed the Yellow Teapot because of the many broken turbos. Enzo Ferrari was worried, but I told him [turbocharging] was the road for the future. The 12-cylinder boxer engine used in the 312 T5 car helped me to convince him about using a turbo; the boxer was too low and big to allow us to use ground effect and side skirts, the weapons of the 1980s.

“In 1980 we introduced the turbo in practice at Imola, but it was more for show than anything else because we were still looking for reliability. We won in 1982 but that was one of the unluckiest and saddest seasons of racing for Ferrari, with the crash that killed Gilles [Villeneuve] and another almost killing Didier [Pironi].”

Soon afterwards, Materazzi left the rarefied world of the racing department to create a road-legal homologation car, the 288 GTO. “One evening, in the middle of 1982, Enzo Ferrari called me into his office,” he recalls. “Enzo showed me a report from the production department, which wanted to build a 3.0-litre V8 turbo engine with about 320bhp. I told him they were wrong, because an engine like that could easily develop 400bhp. He took back the piece of paper and wrote ‘400’ on it. ‘Enjoy making it,’ he told me, adding that if anyone bothered me during the process, I could return to the racing department.”

Materazzi found himself with a very tight schedule. As well as the 288 GTO engine, he had to oversee the enlargement of the 308’s V8 to 3.2 litres for the 328, as well as ensuring that the tax-busting 208 GTB Turbo’s 2.0-litre V8 proved reliable.

There were politics, too. “Enzo Ferrari was not happy when I told him that we would use Japanese IHI turbos for the 288 GTO. He was a friend of the KKK president and didn’t want to upset him. I asked Ferrari to invite this guy personally to test two cars, one equipped with a KKK turbo; the other with an IHI unit. The latter was two seconds a lap faster around Fiorano. After driving both, the KKK boss had to admit that the IHI turbos were better.

“IHI’s secret,” Materazzi continues, “was the material they used to build their turbines and the way they shaped the blades, with a dedicated shape and tolerance for each turbo size. Unfortunately, we couldn’t use the IHIs for racing: Honda had the rights to them, so we had to wait until the F40 Le Mans to use them in our race cars.”

“Enzo Ferrari was not happy when I told him that we would use Japanese IHI turbos for the 288 GTO. He was a friend of the KKK president and didn’t want to upset him.”

Some original thought went into the 288 GTO’s turbo installation. Materazzi remembers with a smile that other engineers considered him crazy in terms of the plumbing and wastegate design. And yet…

“If you look at the maximum torque [500Nm] of my 288 GTO engine and compare it to that of Ferrari’s current turbo cars, which are 35 years younger, you’ll see they are not so far apart in terms of torque per litre of displacement. To me, it means that my engine, without any electronic support, was definitely better.”

One of the purposes of the 288 GTO was to contest the planned Group B racing class. Materazzi was central to this project: “I was asked to work on it on Saturday mornings, so it wouldn’t affect my normal production work,” he recalls.

“I remember the first Saturday morning, entering the office at 8am. I thought I would be alone, because I had asked only a few of my team to come in and help at about 8.30. When I arrived, my whole team was already there waiting for me and excited about this new challenge. These were the people who made Ferrari great.

“We developed two versions, using the workshop of Giuliano Michelotto, an old friend from the Lancia period, because we could move faster if we used his people. The Evoluzione was a new car, with a new, more rigid, chassis. We had two engines, one coded 114 CR with 530bhp and maximum torque at 3800rpm for rallies, and another coded 114 CK with 650bhp for racetracks. After these two prototypes, collectors asked to buy six or seven Evoluziones, offering crazy money, and, through Michelotto and the Cognolato bodyshop, we built them.”

Production of the 288 GTO ended after 272 cars. The Group B category fell apart, so Ferrari, encouraged by the retail success of what was really meant as a competition car, decided to make a successor that would be intended from the start for road use. This, Materazzi reveals, was the origin of the F40.

“The sign-off of the F40 was, for me, one of the last decisions taken directly by Enzo Ferrari. Soon after, his health got worse and worse, and he quickly lost the energy to manage the company. Fiat’s grey men soon took over, hiring a lot of new and foreign people but without a long-term view. We even had a Formula 1 engine with a cast-iron block, I think a sort of a first in Ferrari history.

“When we launched the F40, it was like a bomb exploding. The following morning the commercial director stormed my office, showing a pile of paper. ‘Look at this,’ he stated, pointing to the pile with a serious voice. ‘What a mess you have created. In less than 24 hours we have 900 confirmed orders.’ When discussing production numbers with Enzo Ferrari we imagined we would build 400 F40s…”

It turned out to be a fortunate problem, because Ferrari was heading for trouble. “The problem was that the 348 was a terrible car indeed, and was not selling. Customers were not happy with the products, chassis were so fragile that they twisted very easily, and overall quality was so low, buyers left us. We were losing turnover and cars, so to keep the factory running they had to increase the production numbers of the F40.

“Enzo was not happy. He would have preferred to stop the production well before, but he was no longer part of the decision process. And it was painful for me. When I started my career at Lancia, I used the calculations of the engineer who invented the first unitary body construction with the Lambda. If a car weighs 1000kg, it has to have a torsional stiffness of 1000kgm per degree to be acceptable. The Ferrari 348 was about 380-400; the Stratos, by comparison, was 1500… That was the result of Fiat managing the company, making Ferrari what it is today, an FCA subsidiary in Maranello, completely cheating on the original message given by Enzo.”

That’s a fairly incendiary assessment, and today’s Ferrari management would doubtless protest that it now operates independently, but the issue runs deeply in Materazzi’s spirit. “What I consider one of my biggest achievements is the unconditional trust Mr Ferrari gave me, and I couldn’t continue there anymore. I decided to quit. I was forced by my contract to stay an extra three months, but it was the worst time of my life. That’s when I offered myself with an advertisement in a car magazine: I was looking for a job in an automotive company – any company as long as it was not linked with Fiat.

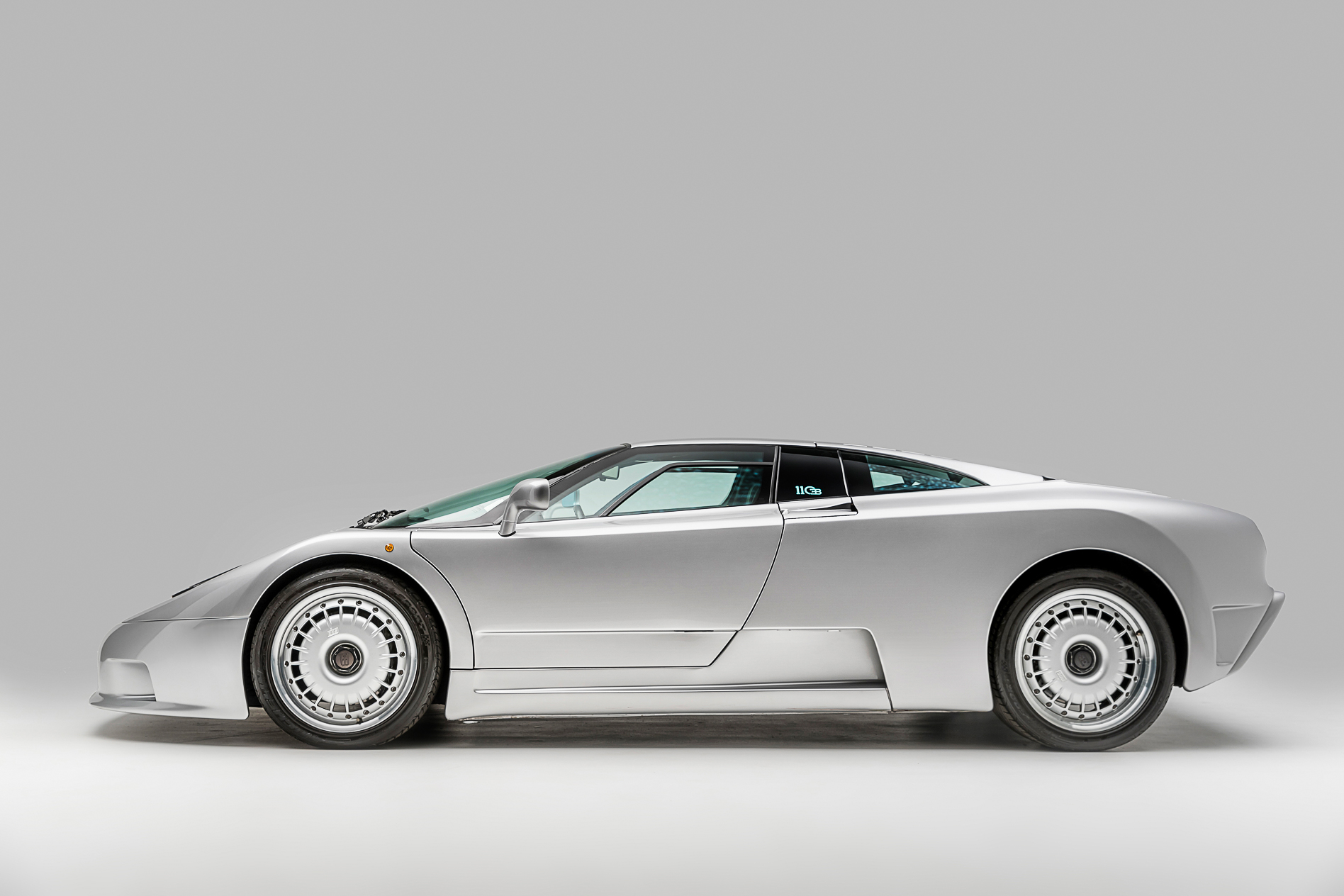

“In 1990 I moved to [Italian motorcycle maker] Cagiva to manage the racing department before going to Bugatti to help in the EB110’s development. That was a car which, in the early 2000s, I further improved as the Edonis [the EB110-based supercar]. I’ve been lucky because I’ve done the work I’ve dreamed of doing. For me, looking for information is always a pleasure. I always want to know more.”

“When we launched the F40, it was like a bomb exploding. The following morning the commercial director stormed my office, showing a pile of paper. ‘Look at this,’ he stated, pointing to the pile with a serious voice. ‘What a mess you have created. In less than 24 hours we have 900 confirmed orders.’”

The F40 brains trust: the men behind the world’s first real hypercar

Project boss: Nicola Materazzi

“I was nervous and reluctant about the F40 proposal because I already had so much work to do. I only accepted because Enzo allowed me to progress the project on my own, without wasting time in meetings to share decision-making. At the end of our meeting, he wrote a note in his diary: ‘Materazzi; no pain in the ass’.”

Designer: Leonardo Fioravanti

“When Enzo talked to me about his desire to produce a ‘true Ferrari’, we both knew that it would be his last car. Extensive research at the wind tunnel went into aerodynamic optimisation, its style matches its performance — the low bonnet with a very tiny overhang, the NACA air vents, and the rear spoiler, all made it famous…”

Test driver: Dario Benuzzi

“The handling of the first prototypes was poor. To tame the power of the engine, we needed to subject every aspect of the car to countless tests and revisions, from the turbos, brakes, dampers, tyres. With no power steering, assisted brakes, or electronics, it demands skill and commitment from the driver, but it generously repays them…”