THERE are some places human beings are simply not meant to live, and baking-hot, back-of-bugger-all Birdsville is one of them.

Much like the Moon, or Mars, which it more closely resembles, it’s both fascinating and borderline frightening to visit, but the idea of staying there seems as mad as going for a swim in a fire pit.

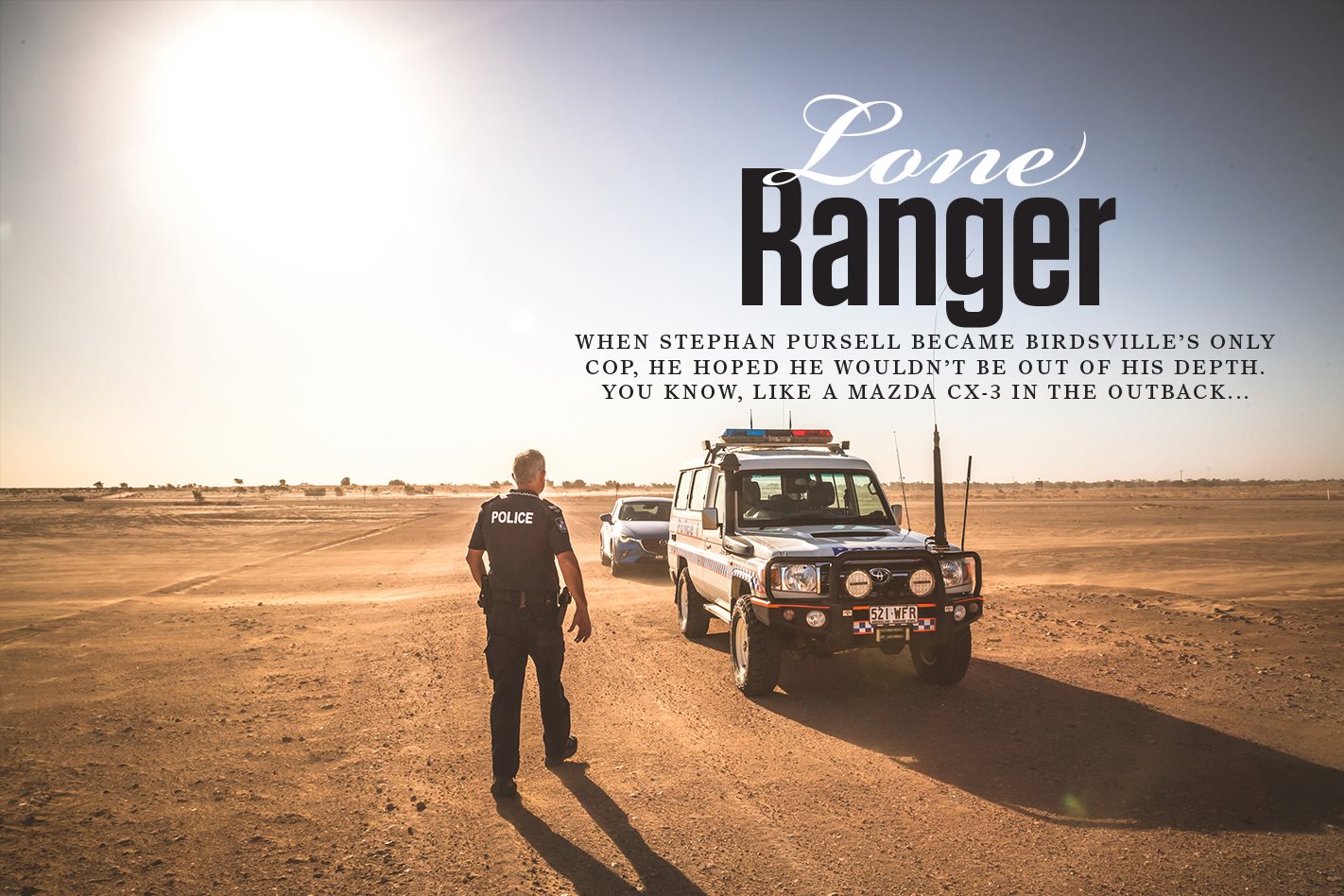

The last time they advertised the local copper’s job – which comes with a beat covering 240,000 square kilometres, or roughly an area the size of the United Kingdom – they had to list it three times, because no one applied.

Unsurprisingly, Senior Constable Stephan Pursell, 52, had never been to Birdsville when he signed up for the job, and even less surprisingly he started having second thoughts before he even got there.

“You drive out over the hills, over the Dividing Range, then you’re out into the Romas and the Charlevilles, lovely little country towns, and then the trees start to disappear, and more and more, and less and less, and then nothing.

“Then you reach the turnoff, from Windorah into Birdsville, when the roads turn to dirt, and then there’s just… there’s just nothing. Not another car or person, then you really start to think, what have I done?”

Our shiny blue faux-wheel-drive compact city slicker looked like a jolly jelly bean dropped in a jar of red hot chilli when it arrived, but it’s quickly been sand blasted. I’ve already eaten so much dirt I fully expect to give birth to a little red-dust snow man in the toilet of my converted shipping container/hotel room later that night.

Pursell is much amused by my discomfort and takes me to see a terrifying photo of what looks like a glooming dust tsunami on the wall of the local servo, run by the even more jovially insane Barry Gaffney, 66, who has lived here his whole life.

Which means he was here before electricity, and air conditioning.

“This dust, it’s nothing, it’s common, you should see the really big storms.”

Not for the last time, I find myself blurting, “But why, why do you stay here?”

“Well, you just get to know the place, you know the heat and the dust storms, you know the flies, they don’t worry us. You see other people coming in here, chasing flies and carrying on, and there’s only about three flies on them, I say come back when it’s nice and green and the flies are really bad,” Gaffney chuckles.

“I couldn’t live down in Melbourne, there’s just too many people. The bloody people.

“People are worse than flies.”

“You should be here in summer, when it’s over 40 for days on end. It’s like the worst Melbourne heat, but it just doesn’t cool down at night, there is no breeze, and you can stick your head outside at midnight and it’s like sticking your head in an oven,” he says.

“Anyway, why don’t we go and do some hot laps around the race track?”

I can count the number of nice cops I’ve met in my life on the fingers of one leg, but I’m really starting to warm to Pursell.

The Mazda makes a spirited run to the winning post, as I whip the driver’s door like a crazed jockey.

Unfortunately, every time we stop to let snapper Wielecki cough up the dust in his lungs, I get that scary, sinking feeling as Pursell walks up to my window in his uniform.

“It’s a bit hard, because when you look at what you’re supposed to test, we’ve got no traffic lights, no controlled intersections, no stop signs, and I have to take them out of town to find a little ridge so they can do a hill start, cause we don’t have hills,” he explains.

His main job, of course, is saving people – generally some of the 50,000 tourists who now pass through each year – who’ve gotten into trouble in one of the harshest environments on Earth (no joke, there’s a remotely monitored Colorbond station in his back yard where the company tests its roofing).

Trail-bike nutters are a particular problem; he’s rescued a dozen so far this year and colourfully describes the noises they make in the back of the town’s off-road ambulance as they clamber over dunes and smash over rutted roads on the way back into town with their broken ribs and shattered collar bones.

It also requires some serious off-roading nous to rescue people who’ve run out of it, yet surprisingly Pursell had done no proper four-wheel driving before moving from his last job, policing a busy shopping centre district on the Sunshine Coast.

The Queensland Police do offer an off-road-driving course, but he’s still waiting to do it. “I reckon I could teach the course by now,” he says. “Some people hate off-roading, and it would have been bad luck if I didn’t like it, but if you love it you’ll want to keep coming back here.

“In the old days, before EPIRBs and sat phones, people could easily die out there if they got stuck. We had a family who set off an EPIRB at Walkers Crossing after it rained recently, and they’d been stuck there for three days. They didn’t see anyone in that time and they were starting to get anxious.

“But when people have rollovers or crashes, it’s tough, because it takes a while to get to hospital. In the city, you have an accident and within 15 minutes the ambos are there and you’re probably in hospital within 30 minutes. Out here, in 30 minutes we’re probably still getting organised to come and get you.”

Pursell and Wayne Car (50,000km on the clock, all of them hard, and racked up in less than a year) will follow the ambulance – sometimes driven by the local ranger, 69-year-old Don Rowlands, an Aboriginal life-long local who knows the area better than anyone, and sometimes by Stephan’s wife, Sharon – because they can’t afford the risk of one vehicle getting stuck without another to pull it out.

Stopping along the way to show us a snake the size of a fire hose, Pursell takes us out to see Big Red, the famous giant sand dune that marks the point where the Simpson Desert proper begins.

The clang and clatter of red rocks and unseen potholes sounds like beasts are trying to get at us through the floor, but somehow the CX-3 keeps it together, and holds its line. Our spines do cop a battering, though, and I can’t tell what the dust proofing is like, sadly, because Wielecki keeps lowering the window to take pictures, turning us into a mobile sand pit.

Our first attempt to climb Big Red ends in predictable ignominy, but with more experience, and the traction control off, we finally manage to climb a slightly smaller dune next door, and find ourselves on top of what feels like Tatooine on a windy day.

When the gale drops and conversation stops, there’s a stillness that’s almost as epic as the wide, wild spaces. It’s one of those places where you feel smaller than the sand grains around you, and suddenly aware of an empty ache inside your chest as the sun begins to melt the horizon and paint the sky.

“It’s the Outback, I just love it,” he smiles, through dusty teeth. “There’s something different about it, the nothingness, and people pay a lot of money and come a long way to experience it, but we get to live it every day.

“And there are these moments, these skies, where it’s started going bright orange on one side of you, but it’s still blue on the other, and above you it’s gone black and the stars are out, and it’s like you’ve got three skies at once and … well there’s just nothing like it. You can’t beat an Outback sunset, you just can’t.

My mouth hangs open as the show he describes goes on above us in slow motion, and I have no more questions.

I now know what it feels like to be a toddler desperately trying to keep up with an adult as the LandCruiser tears off effortlessly into the distance and I try to keep up, balancing indelicately with two wheels on the edge of the track and two on the raised centre that would gut my fearless yet outgunned CX-3 like a fish.

Finally, we find the camels and some wild-eyed and desperate-looking tourists who’ve just spent six days trekking across the Simpson on foot (they don’t even ride the camels, they just use them to carry their gear). I’m slightly frightened to shake hands with them in case their insanity is contagious.

It’s already too dark to fly a plane to her, so the Royal Flying Doctors want Pursell’s crew to go to the rescue, a 600km round trip across brutal terrain, at night.

Stephan laughs ruefully when we ask whether we can follow them in the Mazda, so we bravely set off to research the historic Birdsville Hotel (it’s excellent).

Just before 8am the next day they roll back into town to meet us, and the doctor who’s flown in, at the local medical centre and all three of them look surprisingly fresh, despite no sleep and a nine-hour road trip.

“We’re bringing her back over sand dunes, so you can’t take it easy or you won’t get her back, you have to hit ’em hard,” Rowlands explains. “It can’t be easy in the back.”

Cameron has no doubt the woman would have died if they hadn’t gone to her aid, and quietly admits he’s concerned she still might not make it, even after being airlifted out to Mt Isa. Apparently she had an existing condition, had been suffering diarrhoea for a few days before setting out and “just should never have tried to go out there”.

It’s all in a day’s work for the country cop, the nurse and ranger Don, of course, a day that’s not over yet because they can’t go to sleep. There’s no one else to do their jobs.

Feeling like we should probably get real jobs, Wielecki and I bid Birdsville and its bonkers residents farewell, help push our remarkably intact CX-3 back onto its truck transport, and set off for the long journey home.

I still think they’re all mad for living out there, but here’s the funny thing; for a few days, as I attempted to speed back up to life in the big city, I couldn’t stop thinking about Birdsville, and looking up and missing all those stars.

There really is something about outer space, and you don’t even have to leave Australia to experience it.

For a town with a population of “about 70”, which falls closer to 30 in the heat of summer, when even the locals run scared, Birdsville has more than its fair share of interesting characters.

Pursell introduced us to quite a few, but then mentioned, in passing, that we might want to chat to the local nurse, Andrew Cameron, who’s “an interesting bloke, and a dead ringer for the Monopoly man”.

Not only is Cameron the only guy providing medical help to the community on most days (a doctor flies in once a week to hold a clinic), he’s a volunteer for the Red Cross, work which has taken him to war zones in South Sudan, Kenya, Georgia, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Clearly feeling that those experiences weren’t dangerous enough, he also flew to Sierra Leone in 2015 to help out with the Ebola crisis.

“I’d put them through this chemical shower, which we called the Happy Shower, and then give them a hug, which was the first physical contact they’d had with another human in weeks, so that was nice,” he says.

One piece of advice, if you ever meet Cameron and he asks if you’d like to see some of his work photos, say no. I may never recover.

As Pursell says when discussing the locals, and those who work on the massive stations outside town, “these aren’t just ordinary people out here, they are extraordinary people doing extraordinary things.”