Trying to parse exactly how much happens in a century is a difficult task. We can all objectively picture the timeline. 100 years. 1200 months. 5214 and a bit weeks. 36,500 days. 876,000 hours. But it’s what happens during those unstoppable 52,560,000 minutes that we struggle to comprehend.

Interspersed between the individual moments of our collective memory the relentless nature of progress has changed the world in to a state almost unrecognisable if we put the here and now beside 1921.

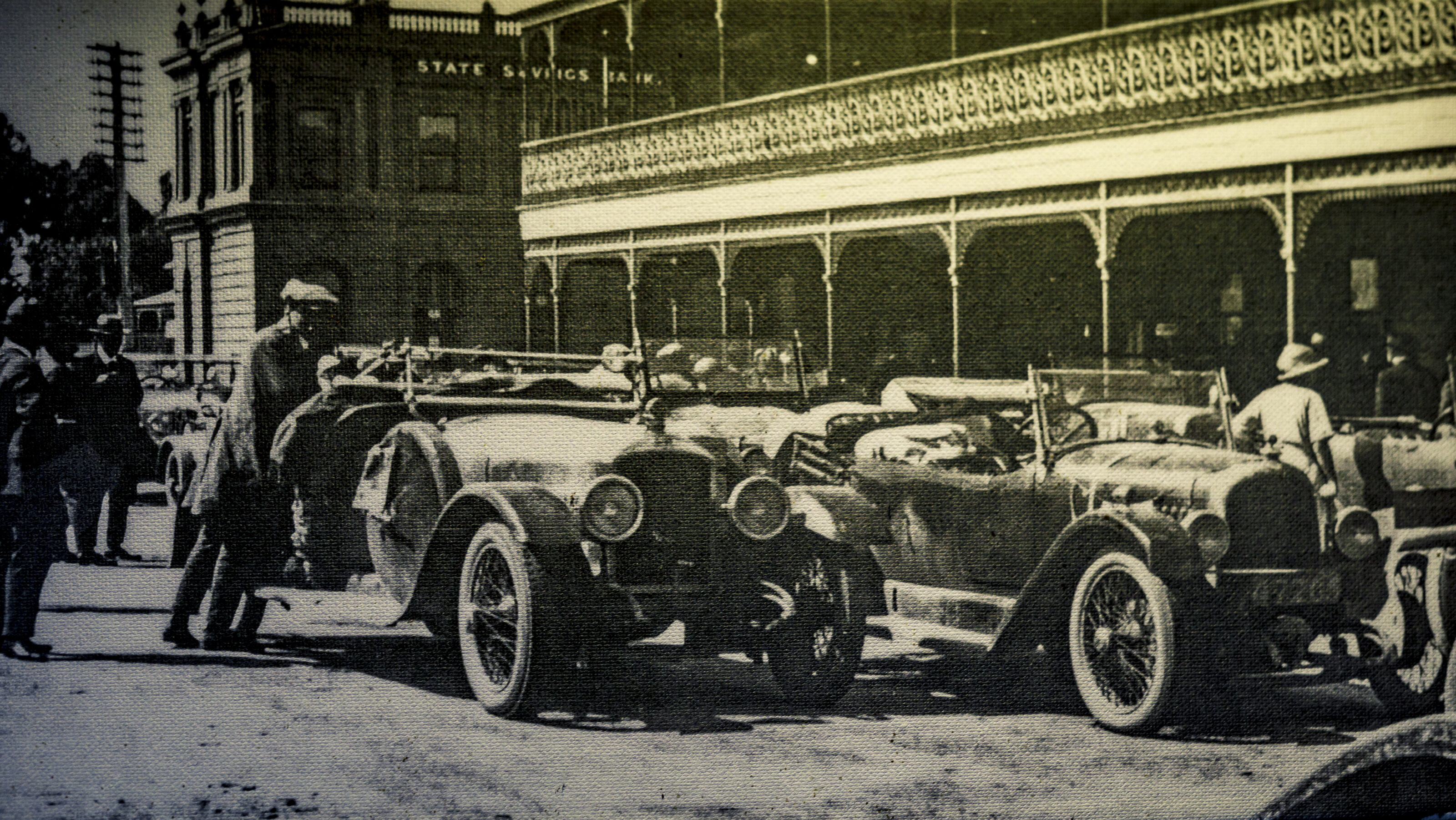

A hundred years ago Australian automotive and racing history was made with the original 1921 Australian Alpine Rally. It is our country’s oldest continuously running motorsport event, beating the Australian Grand Prix by seven years.

The original event wasn’t a rally in the sense we know it, instead being a 1000 mile reliability trial with a complex points system that criss-crossed large parts of Victoria. Since 1921, the Alpine Rally has morphed and changed into a bi-annual historic gravel stage rally.

COVID-19, like so many things, nuked official plans for centenary celebrations from orbit. MOTOR wasn’t going to allow this anniversary to pass in such a meek fashion. So, to honour those intrepid competitors that took part in the original Alpine Rally, we decided to follow the same route that they did in 1921.

Instead of taking eight days, we planned to complete the 1600km largely highway-less journey in half the time. The ‘we’ being yours truly, pint-sized photographer Ellen Dewar, Trent Giunco, and MOTOR’s long term Focus ST.

Starting festivities for 1921 took place at The Haymarket building which has since been demolished, so we move our start line to Albert Park. We leave Melbourne early Sunday afternoon. I’m lulled into a false sense of belief that this won’t be that hard a challenge. I’ve driven similar distances in a single day, how hard can it be to do it across four?

We make good time early on, escaping the urban sprawl quickly and charging toward our first stop of the journey at the Criterion Hotel in Sale. This is the same venue that the original competitors stopped at for lunch. Inside, the walls are adorned with photos from the era. I’d happily spend the entire afternoon basking in the afternoon spring sunshine, enjoying the Criterion’s fine food and drink, but the road beckons us to continue.

We slip into Lakes Entrance at night. The town is sleepy with a few passing cars the only sound disturbing the creaking of fishing boats. A minute shy of six and a half hours behind the wheel, travelling 371km. I stare at the ceiling of the motel room doing the mental maths on what that means for the rest of the journey. This is going to be harder than expected.

Melbourne to Lakes Entrance – 322KM

Our first day is the one that most closely resembles the original itinerary. With dual carriageways almost the entire distance it was only photography and sustenance requirements that slowed us down. If you find yourself near Sale, The Criterion is a must-visit. Get the parma, trust us. The view from the road that winds down into Lakes Entrance is spectacular, particularly at sunrise.

Day two: Part one

I’m back in the hot seat for the early morning stint, slinking back out of Lakes Entrance and charging onward north. The sun is beautiful and golden by time we pass through the Tambo Valley, which spreads rolling and vast like an emerald ocean to the east. The monotony of highway driving is banished, with our new guide the Great Alpine Road revealing its delights almost instantly.

The sweeping, cambered bends draw my eyes from the green pastures to key into the ST. In the grand scheme of the route, the section from Lakes Entrance to Omeo is relatively tame, but it’s enough to satiate, with the ST proving to be an inspired choice.

When we stop in Omeo I immediately head toward the local information centre. I’m in search of a paper map of the region, hoping it will help me capture some of the old school magic that the original competitors enjoyed navigating these roads 100 years ago.

Inside I find an incredibly helpful lady. But as I inform her of our journey her eyes glaze over. She knows of the current Alpine rally, but the 1921 event is news to her. Making matters worse there are no maps, and my phone reception has disappeared entirely. Drats. The path from here is a problem for Trent now. – CK

Day two: Part two

As I slide behind the thick-rimmed Focus ST steering wheel and into the heavily bolstered Recaro driver’s seat, it’s 9.07am, nine degrees Celsius and our trip timer has clicked over the nine-hour marker. I depress the clutch and push the start button. It’s a thoughtless process that seems all too easy and nothing like that of 100 years ago where three minutes were set aside for engine cranking.

Leaving Omeo the sun is shining and the countryside is a lustrous shade of green. It’s as though everything has grown while the city slickers have been locked out of the regions and Mother Nature is showing off. So too is the Omeo Highway, which in its entirety is a 163km stretch of tarmac that connects north-east Victoria to Gippsland and the Victorian Alps. If you haven’t driven this road, you must. No questions asked.

For me it’s a rude initiation having zero previous exposure to the now halo Focus. Yet, this isn’t about speed. The press bumf for the original 1000-mile rally states: “The club particularly desires to impress on the general public that the event is in no way a race, but a Reliability and Efficiency Contest at ordinary touring speeds”. In fact, penalties were issued for arriving too early at the finish line for a particular section. However, with a 206kW/420Nm hot hatch at my disposal, it’d be remiss of me not to stretch its legs.

Right-hand hairpins have wonderful vision and build confidence. As do the dynamics of the Focus, which have matured from the snap-oversteer-happy previous-gen. Now, with a bit of a work from the communicative steering, you can engage the rear axle with corner-entry yaw that transitions progressively into traction as the electronically controlled, Borg Warner mechanical LSD bites into the bitumen. With a positive shift from the six-speed manual and an intuitive rev-match system, the Focus covers ground at an alarming, grin-inducing rate.

I pull over at the Blue Duck Inn at Anglers Rest and realise the brakes need cooling; remaining stationary will turn them into molten lava. Unlike the cars of yesteryear, I fatigue long before the ST does despite the temperature being generated. I cool off by drinking from the Mitta Mitta River, the water fresh and chilled as it flows from the melting snow-capped Alps like a natural refrigerator.

While we try to stick to the original route as much as possible, the expansion of Lake Hume in the ’50s and the resulting 8km shift of Tallangatta renders this impossible in 2021. Google Earth bares all, with the old town layout visible, but to our eyes it’s just an expansive body of water. And with recent heavy rain, it’s currently bursting its banks.

Hightailing it to Bright via Yackandandah (where Kirby finally gets the map he’s been searching for) becomes the top priority. We jag a park and eat pizza at the Bright Brewery, the leftovers of which will be needed later for sustenance.

Traversing the top of Mount Hotham is no longer the nerve-wracking experience it used to be. The sheer drops remain, but advancements in road safety mean that barriers now remove most of the danger. While we don’t see a large sign with a skull and cross bones with the word ‘REFLECT’ brandished across it, something entrants in the original rally had to digest along with the enormity of the terrain, signs warning us of steep declines are omnipresent.

The run up to the Mount St. Bernard Hospice formed one of the timed hill climb sections, and it’s easy to see why. That marker is around 5000 feet (1524m) above sea level, however, we push on to Danny’s Lookout, which is 1705m above sea level. Although, the road surface isn’t as billiard-table smooth as you’d expect on the top of Mt Hotham, the Ford’s adjustable dampers do just enough to save the ride quality. In yesteryear, on the unsealed route, it would have been a different story.

As written in Bob Watson’s book, The Great Alpine Contest, one of the competitors “lost control of himself completely” summiting Mt. Hotham and that he had to be restrained. Out of the three of us, after more than 14 hours on the tools and on the road today alone, it is snapper Ellen whose patience frays the most. After all, she is the one braving the elements. Night descends and all our brains are fried. Tempers can easily fray. But our camaraderie is bolstered by the unity of the shared common goal. We’re warriors of the night.

Turn by turn, we slink down the mountain to our overnight stop in Harrietville with headlights ablaze, highlighting our path for weary eyes. In these dormant hours of darkness, traffic is non-existent. And yet, we find ourselves parked at a roadworks red light. After what feels like an age, the crimson glow is yet to flick to the anticipated shade of green.

“F**k this” I hear from the passenger’s seat. And with that, in a moment of exasperated irony, we get the go-ahead. If this is how broken we feel in a modern car, the reality of 1921 is even harder to fathom. At 9.20pm, the 2.3-litre turbo four-pot finally falls dormant. – TG

Lakes Entrance to Harrietville – 481km

Put this into your Google Maps and save it for a weekend adventure. There is no need to fly all the way to Europe for motoring nirvana when this is in our own backyard. Hell, you could even break it into several days there is so much to take in. This is where our recreation makes the most time on the 1921 rally.

Down on power, and dealing with little more than a horse track, the original competitors were forced to make frequent stops. By time 1922 rolled around, the Alpine Rally cut west from Omeo, climbing directly over Dinner Plain to Mount Hotham. A disappointing change in our opinion.

Day three

My alarm pierces through the silence like gunfire after surrender. It’s just before 5:00am and, blurry-eyed, I have to position myself in the shower so as to not fall down the well that is its drain. Character, it seems, is offered for free in a cheap motel. Yet, the brief respite before the day ahead has me thinking of how much we take modern motoring, and reliability, for granted.

We don’t check under the bonnet before taking off – doing so 100 years ago would see us penalised, apart from a supervised flooding of the carburettor once every morning. And despite Kirby’s delight and fixation on the paper map he’s purchased, the reality is Apple CarPlay (or Android Auto) infinitely outsmarts his analogue ambition. I plug in Mount Buffalo and pull out of the driveway with the twin exhausts emitting plenty of cold-start steam.

While in 1921 entrants enjoyed an evening celebration at the Mt Buffalo plateau (“Garden of the gods”), we’re instead greeted by a peloton of Lycra-clad fitspo specialists at sparrow’s fart. It’s hard to imagine tackling this route a century ago, but right here, right now, the Focus is a bloody riot. The chassis is taut, meaning even with the multi-link rear axle, the ST can’t help but cock a trailing inside leg when hunting an apex. What’s more, the crack of the exhaust on downshifts is intoxicating.

My enjoyment is curtailed somewhat by sudden fixation on the distance-to-empty readout. We departed before the opening hours of the local servos, which only fuels my range anxiety. Economy tests were a part of the deal 100 years ago, but I wasn’t expecting to hyper-mile it to Wangaratta (via Myrtleford). We make it at a canter. And yet, drama ensues with the EFTPOS system crashing at the service station. Kirby is tasked with paying.

Returning to the car, he tells us that a rather flustered young attendant had misheard a customer, leading to her projecting “if anyone leaves, we’re calling the cops”. Everyone pays. However, it’s an insight into how our lives are now so dependent on technology that if it begins to falter, slight cracks appear in the social code.

The trip in and out of Wang’ is also the only time we see the mighty Hume Highway, although we merely traverse it twice and never actually drive on it. Recreational stops were a part of the original route, so we head to Eildon via Mansfield and Alexandra to the local grocery story and load up on chips and beverages. The Goulbourn River and Lake Eildon are a hive of activity, and we set up stumps in the shade to watch myriad boats and jet skis on the water.

COVID-induced lockdowns have ravaged the tourism industry and it’s heartening to see smiling faces and hear laughter far from the CBD. Fun and whimsy has returned to the country, along with a much-needed monetary injection.

There is an insatiable vibrancy flowing through the camp sites and surrounding towns around the body of water. It’s fitting given that one of the by-products of the original rally was to show off the regions to the masses for a hoped tourism injection.

It’s the end of Day Three and the gravity of what we’re achieving is really hitting home. The thought of returning to the ‘big smoke’ is almost daunting. From above, Melbourne’s road networks convey a sea of abandoned spider webs; serenity makes way for chaos. That’s ahead of us tomorrow.

For now, as the odo nears 1500km and I hand the ST’s key fob back to Kirby, it’s time for a steak, a drink and some kip in Marysville. Clocking off 12 hours after the day started feels like an early mark. – TG

Harrietville to Marysville – 428km

Where Hotham and Falls Creek get most of the Alpine love, Mount Buffalo is also a fantastic experience. A favourite of local cyclists, the tight switchback hairpins only just take top billing over the truly fantastic views. Whitfield-Mansfield Road is the dark horse of the entire rally, but equally worth being graced by you and your metal steed. Recently lowered speed limits are disappointing, but much of the road’s character and challenge remains.

Day four

We are on the road before the sun’s rays breach the darkness once again for the final day of the journey. In the gloom I mistake the outline of a wallaby that lies dead as a pothole that I can simply pass over without worry.

Its not until I am upon the stricken macropod that I realise it has swelled up to a point that if I continued on my current trajectory, I’d simultaneously obliterate the Focus’ front bumper, and perform Victoria’s most gruesome vehicular drop kick. Thankfully the ST responds with composure as I wrench the wheel aggressively to and fro. If Ellen wasn’t awake before, she is now.

Our destination is the Black Spur. In 1921 competitors also faced the now iconic road in the dark, with one team rolling into a ditch and breaking an axle. A rescue team was mustered from Healesville to right the vehicle, allowing it to continue and complete the rally. Stretching for 30km, in isolation the Black Spur and its buttery smooth hot mix is one of the finest pieces of tarmac in the state.

However, a consistent police presence, and heavy traffic, has choked its personality. We make our way through towering gulleys of mountain ash as the sun rises and there is already a steady stream of vehicles doing the same – mostly dual-cab utes. The canopy disperses as we head toward Healesville and the inky sky that encased us is now bright and clear. There are no signs of the heavy downpours that would hound us later in the day.

The CBD is eerily quiet, another side effect of COVID, but it allows us to capture some photos of the Focus in front of the Herald Sun building. Crowds gathered here to applaud the competitors as they passed through a century ago. One of the loudest cheers was reserved for an all-female squad. No one pays us any mind.

It’s not until we ascend the Westgate Bridge that the first fat droplets of rain begin to fall. It only gets heavier throughout the day, turning what should be the easiest part of the trip into one of the most challenging. Between Melbourne, Bacchus Marsh, Ballarat, and Geelong is where we are tested the hardest. As we charge head-first into the rain storm on the final stretch toward Geelong, a slew of wind turbines emerge from the fog like towering alien constructions. I chuckle quietly imagining the difficulty a 1921 native would have comprehending this visual.

Our penultimate stop is outside the old Ford plants in Northern Geelong. Four years after the rally swept its way through G-Town Ford Motor Company began assembling Model Ts using complete knock-down kits from Canada. Before a century could pass, the entire local industry has become extinct.

Due to the widespread adoption and construction of a little known design called the “bridge”, we have avoided having to get the Focus’ sills wet in water crossings. The 1921 competitors were forced through numerous challenging river crossings, and I’d gloated internally during the preceding three days that we remained free of such indignation.

That is, until the final handful of kilometres of inner-city driving, when continuous heavy rain prompted parts of the road network to flood. Despite this final challenge we are able to wade safely back to Albert Park where our journey started what seems like an age ago. These have been the longest four days of my life.

The final stats are as such. Odometer: 1916.6km (the extra distance is down to photography requirements). Ignition time: 38 hours, 15 minutes. Average speed: 50km/h.

Three Buicks were entered in the 1921 event, finishing the petrol contest in first, second and fourth. The most efficient of the trio achieved 24.24 miles per gallon, equivalent to 9.7L/100km. ‘Our’ Focus, still reeking of garlic from the cold pizza eaten atop Mount Hotham, with 100 years of technological advancement under its bonnet records a total average fuel consumption of just 9.1L/100km for the trip. Progress, eh?

Archie Turner was the victor of the Alpine Rally in 1921. A century later there is no spraying of champagne. We aren’t greeted by a throng of enthusiastic onlookers. Instead, I stand in the rain as Trent hides in the car as Ellen takes one last photograph. We disperse without fanfare. As I head to the much-needed comfort of home I reflect on a century of motoring evolution.

Throughout our entire journey, even when we ate at the same places and gazed upon the same vistas, the experience of those 31 competitors in 1921 seems alien. What they achieved, and the motoring spring that flowed forth as a result, has had an indelible impact that is felt today.

I don’t have enough of an ego to entertain our journey achieving a minutia of the same influence, but I can’t help but ponder what the reaction to this four-day trip will be in the year 2121.

What would a kid born in the year 2093 think as they flick through a copy of MOTOR that their great-grandparent stored dutifully in the attic (thanks for that, dear reader). Are they similarly befuddled as I am now?

Wondering how we completed such a journey in the manner we did – changing gears ourselves, toiling at a wheel incapable of controlling the car unsupervised for nearly 40 hours, propelled by combustion chambers. They may see that journey as punishing. I won’t claim it wasn’t, but be rest assured it was also liberating. Long may the driver’s spirit reign. – CK

Marysville to Melbourne – 374km

We regret to inform you that unless you are seriously dedicated to recreating historic rallies like us, there isn’t much in the way of traditional driving fun to be found in this part of the route. The Black Spur is little more than a tourist drive, and the road quality west of Melbourne leaves plenty to be desired.

We recommend

-

News

News2020 Ford Focus ST revealed, confirmed for Australia

Ford’s Golf GTI rival touted as “the most Jekyll and Hyde” ST yet

-

Features

FeaturesWRC Rally Australia Review

MOTOR’s take on what went down at Rally Oz, and how each driver performed.

-

Features

Features2020 Ford Focus RS preview

Watch out A45, Ford is readying its next 300kW hybrid hyper hatch