You probably saw this coming, right? But seriously, we could not nominate any car for the top step of this particular podium other than the mighty GT-HO Phase III.

The Phase III doesn’t just represent the fast Falcon family: it is the all-time champ. The greatest ever. The One. It was an immediate sensation on its release in ’71, and it went from strength to strength until it emerged at its current unassailable position in our hearts and minds.

But why? Why is it that the Phase III is the only Australian production car ever to make it to seven figures at auction (admittedly a few years back when prices went troppo)? Why is the car instantly recognisable, even among those who weren’t born when it was roaming the streets as a brand-newie? Why is it king?

Okay, so that played into the XY GT-HO’s hands, making it an instant last-of-the-breed kind of deal. But beyond that, 1971 was still a time when winning at Bathurst was everything to a car-maker. In fact, without the hunger to succeed at Bathurst (and flog a whole mess of GSs and Fairmonts in the process) cars like the GT-HO and its ilk wouldn’t have happened in the first place.

The rules of the day were roughly run-what-you-sold. If you didn’t have a production car with finned alloy brakes or a four-barrel carby, you didn’t have a race car with that stuff either. It’s a far cry from today where the only Falcon in a Falcon Supercar is the headlights and tail-lights. And that’s about it.

Moffat had triumphed again, followed by Barnes and Skelton in second, David McKay in third, John French fifth and John Goss sixth. Only Colin Bond in the HDT XU1 could split the Ford pack, finishing fourth. Twenty cars had been under the Mount Panorama lap record in qualifying, but Moffat was fastest with 2:38.9, a full three seconds ahead of John French.

Nor did the Canadian have it all his own way: a beer carton from the crowd got scooped up on to the grille of Moffat’s car, threatening to overheat the engine. It didn’t and the carton was removed at the next pit-stop. Needless to say, magic had just happened.

Here’s the skinny. For a start, only 300 Phase III GT-HOs were made (although there are only about 700 left…) and while Ford claimed only incremental improvements over the basic GT on which the HO was based, the truth is that there were a lot of differences. Ford just didn’t want to make a song and dance about them, since it already had the insurance industry pretty well spooked.

Visually, there are really only two external differences between the GT and the GT-HO. That’s the front and rear spoilers. The GT had the shaker and it had everything else bar that plastic front air-dam and the fibreglass rear wing. Inside, it was a similar story: the HO had a choke knob where the V8 badge went in the dashboard of the GT, and the decal on the glovebox of the GT-HO said GT-HO.

Rear brakes for the HO were drums but slightly wider and finned, again to help with heat dissipation. Rear wheel-cylinders were also bigger. The diff centre was tougher and you could have either a normal LSD or a rather fearsome Detroit Locker that was all about Bathurst and not much else.

Like the GT, the HO got a nine-inch rear end but there were little bits and bobs added to mount things like the sway-bar rubbers. Some cars had 28-spline axles, some 31-spline, and a range of diff ratios could be specified when you placed your order.

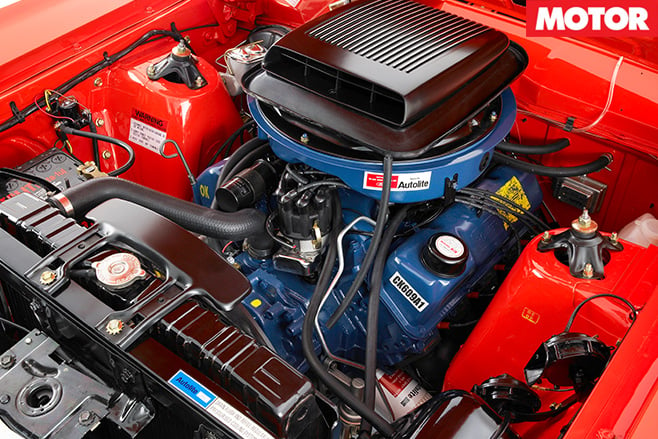

Now, if you know your Ford codes you’ll know that HO stood for Handling Option. But that was Ford deliberately skewing the emphasis, again, to placate the shiny-bums in the insurance world. In fact, the engine was extensively modified over the 351 Cleveland in the GT and while power outputs were fudged at the time and pegged at 300 horsepower, the reality is probably closer to 380 or so (call it 285kW… not bad for 1971).

The shaker might have been the same as the GT’s but the heat-riser was blanked off and air flaps removed to supply cold air all the time. Beneath was an HO-specific vacuum-secondary Holley carb measuring 780cfm and made specially for Ford. The intake manifold was hogged out for better flow and the distributor converted to mechanical (not vacuum) advance.

Naturally, the whole thing was hand assembled and balanced, and racing touches like a big harmonic balancer and a baffled sump were also part of the HO deal. Headers were a natch and blew through a twin system, and stuff like a bigger radiator was also added. Finally, a rev limiter was fitted to pull the pin at 6150rpm. It was mounted on the firewall on the passenger’s side and was famously disconnectable.

So much for the hardware. What was a GT-HO really like to drive? Well, I’ve been very lucky enough to sample the mighty Phase III myself. Yes, they’re a bit heavy to drive with no power-steer and that big clutch, but once you’re moving they’re remarkably docile. Actually, docile’s the wrong word because they’ll still buck and spit a bit if you’re lazy with the gearbox or clumsy with the clutch. But the GT-HO will cruise pretty comfortably, and when the music stops it’ll get across 400m in a mid-14. The rest of the four-door world was years catching up with that.

When you drive a Phase III – and this is no gimme with performance cars from the ’70s – you can absolutely see what the fuss is about. Then and now.

IN DETAIL Engine: 5763cc V8, OHV, 16v Outputs: ‘224kW’/515Nm Weight: 1524kg Price: $5250

What’s our fave Falcon? Check out MOTOR’s take on the top 10 Fast Ford Falcons ever made here.