THINGS can go wrong when you’re off-roading. It’s just the nature of the beast. Travelling in modified four-wheel drives to the far corners of one of the world’s most isolated countries, and then driving the wheels off the rigs means something will eventually go wrong.

Your preparedness to act is the deciding factor between a life-endangering situation and a quick recovery. Over the past 12 months we’ve run you through not only what recovery gear you should have in your 4x4 but the ins and outs of how to use it and how to improvise when you need to.

This issue we thought we’d take it to the extreme: What do you do when you’re in the thick of it and the gear you need fails? A busted winch, a failed snatch strap or a seized high-lift jack can all leave you stranded if you’re ill-prepared.

SITUATION 1: SNAPPED SNATCH STRAP

A SNAPPED snatch strap is common. Over time the fibres in the weave can weaken and fray, which is why we always refer to them as a consumable item. If you notice your snatch strap has fuzzy edges or visible damage and you head off anyway, then you’re a peanut. That said, sometimes things happen. If you’re axle-deep in mud and you’ve just snapped your last snatch strap you can do a field repair to get it back in one piece. Is it recommended? No. Will it work as a permanent fix? Not even close. Will it allow you to continue the recovery when you’d otherwise be stuck? Yes.

A SNAPPED snatch strap is common. Over time the fibres in the weave can weaken and fray, which is why we always refer to them as a consumable item. If you notice your snatch strap has fuzzy edges or visible damage and you head off anyway, then you’re a peanut. That said, sometimes things happen. If you’re axle-deep in mud and you’ve just snapped your last snatch strap you can do a field repair to get it back in one piece. Is it recommended? No. Will it work as a permanent fix? Not even close. Will it allow you to continue the recovery when you’d otherwise be stuck? Yes.

The technique is known as a water knot and is used when flat straps need to be joined. You’ll lose around a metre of your length, cut your working load in half, and lose the rubber-band effect of a snatch strap; so once the strap is connected again it’s time to reach for the shovel. Think of your patched-together strap as a tow strap and you’re on the right track

SITUATION 2: SNAPPED WINCH ROPE

THERE are about three million reasons why rope is a better option than wire for a 12V winch – in fact, its only downfall is that it doesn’t hold up to abrasion as well as steel cable. Joining winch rope together is incredibly easy, and it’s the technique used by manufacturers to put loops in the end of rope to hold a bow shackle or hook. While it might look solid, winch rope is already made of individual strands all entwined together with a hollow core. If you grab a section of rope and bunch it up you’ll see not only the hollow core but that the individual strands separate. It’s these separations, and the hollow core, that you’ll take advantage of.

THERE are about three million reasons why rope is a better option than wire for a 12V winch – in fact, its only downfall is that it doesn’t hold up to abrasion as well as steel cable. Joining winch rope together is incredibly easy, and it’s the technique used by manufacturers to put loops in the end of rope to hold a bow shackle or hook. While it might look solid, winch rope is already made of individual strands all entwined together with a hollow core. If you grab a section of rope and bunch it up you’ll see not only the hollow core but that the individual strands separate. It’s these separations, and the hollow core, that you’ll take advantage of.

The process is simple. Overlap the two lengths by around 300mm. Weave one in and out of the other at 30mm intervals three times before opening the centre up and sliding the tail inside. Repeat the process on the other end. A hollow pen tube taped to the end of the rope will let it slide easier.

SITUATION 3: BROKEN BOW SHACKLE

A BROKEN or lost bow shackle isn’t exactly a common situation. They’re incredibly strong, so you’ll generally be fine. That said, they play an integral part of a winch or snatch recovery, and without them you’re dead in the water. So, what do you do if you don’t have one? The solution is relatively easy; although, you’ll lose 1.5m of winch line for the fun of it.

A BROKEN or lost bow shackle isn’t exactly a common situation. They’re incredibly strong, so you’ll generally be fine. That said, they play an integral part of a winch or snatch recovery, and without them you’re dead in the water. So, what do you do if you don’t have one? The solution is relatively easy; although, you’ll lose 1.5m of winch line for the fun of it.

Run your winch line out and (remembering the splicing technique from before) lop 1.5m off the end before splicing in a new loop. With the length you’ve cut out you can make a soft shackle. Essentially the technique involves halving the rope and then feeding one length through the other, then popping it out halfway to make a lanyard knot. The outer sheath can slide, opening and closing the hole. It’s simple stuff, but best practiced beforehand. The tighter the knot, the stronger the shackle will be. They won’t work as well as the store-bought options, but done right are more than strong enough for a recovery.

SITUATION 4: SEIZED HIGH-LIFT JACK

There’s not a lot that can go wrong with high-lift jacks. Knock-off imports can struggle with binding due to the standard (the spine) bending and binding on the runner. If that happens you’re generally out of luck. Short of that there’s very little to go wrong, so it makes for a simple bush repair.

There’s not a lot that can go wrong with high-lift jacks. Knock-off imports can struggle with binding due to the standard (the spine) bending and binding on the runner. If that happens you’re generally out of luck. Short of that there’s very little to go wrong, so it makes for a simple bush repair.

In 90 per cent of situations binding in the up or down direction is a case of the two climbing pins being either clogged with contaminants from use or catching on rust. Cleaning before and after use with a fresh squirt of silicone spray will prevent this, but if it happens in the bush a squirt with degreaser is often enough to get things moving freely.

High-lift jacks can be overloaded and will fail. To prevent them from crashing down there’s a sheer pin in the handle that will fail before the climbing pins. They act as the fuse, so if that blows replace it and reconsider your loads. Using a stronger bolt will make the climbing pins the weak point, which could have deadly results.

SITUATION 5: SOLENOID FAILS

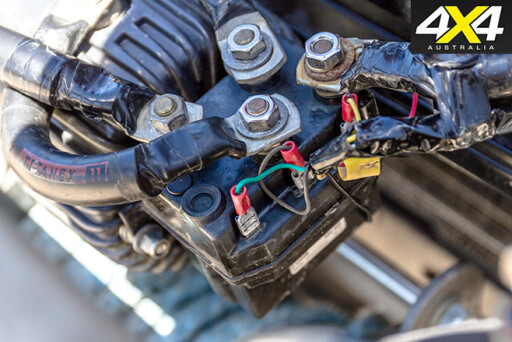

An electric winch is only as good as its solenoid. Solenoids are in charge of getting power to your winch and distributing it exactly where it needs to go. When they fail, your winch is just a heavy ornament. With a little thinking you can completely bypass the solenoid with some jumper leads.

An electric winch is only as good as its solenoid. Solenoids are in charge of getting power to your winch and distributing it exactly where it needs to go. When they fail, your winch is just a heavy ornament. With a little thinking you can completely bypass the solenoid with some jumper leads.

On the top of your winch you’ll have three posts: the armature (A) connection, closest to the motor end cap; and the F1 and F2, both closest to the winch body. Connect the A terminal to F1, and then connect F2 to the positive terminal on your battery. To winch the opposite direction connect A to F2 and F1 to the positive terminal. Not all winches run the same direction, so it pays to pull a metre or two of rope off your drum before testing to triple check which way is which.

With an exposed winch motor, connecting directly to the terminals is easy; if your motor is buried deep inside your bar you may need to connect to the cables running to your solenoid instead. The same process applies but will take some figuring out on the spot.

SITUATION 6: WINCH CONTROLLER FAILS

DEPENDING on the brand of your winch, the controller could rate anywhere between “sturdy as an ox” and “what the hell is this”. Unfortunately for those with the latter they’re incredibly easy to break, with a drop on a hard surface or in a stray puddle all it takes to finish them off for good. If you don’t have back-up in-cab controls, or simply can’t find your control in the first place, you’ll be stuck trackside with a working winch and no way to actually make it work.

DEPENDING on the brand of your winch, the controller could rate anywhere between “sturdy as an ox” and “what the hell is this”. Unfortunately for those with the latter they’re incredibly easy to break, with a drop on a hard surface or in a stray puddle all it takes to finish them off for good. If you don’t have back-up in-cab controls, or simply can’t find your control in the first place, you’ll be stuck trackside with a working winch and no way to actually make it work.

If you’re running a winch with a modern solenoid set-up, they’re actually incredibly easy to jerry-rig yourself. Pop the cover off the control box and you’ll usually find four wires. One will send power to the controller; one will connect to the negative terminal on your battery; and the other two will send power to the corresponding terminal for winching in and winching out.

In modern solenoids the middle tab needs to be connected to the negative terminal of your battery, with positive going to one of the others.

COMMENTS