Fifty-four seconds. It seems like eons, especially when all you have to do is fire a couple of bolts into a car moving glacially along a moving production line.

Except that the pressure is on. There are 3400 people and hundreds of stations in Hyundai’s Nosovice plant deep in the Czech Republic to bring together the 23,000 parts that make up a single car. One glitch can stop the line that snakes through the welding shop, the paint shop and final assembly, creating a sizeable hiccup in the just-in-time production that results in 350,000 cars exiting what is one of Hyundai’s most advanced plants each year.

My job today is very different from a typical Wheels assignment. Usually we’re at the end of a production line itching to swipe the keys of a new model and give it a suitable thrashing.

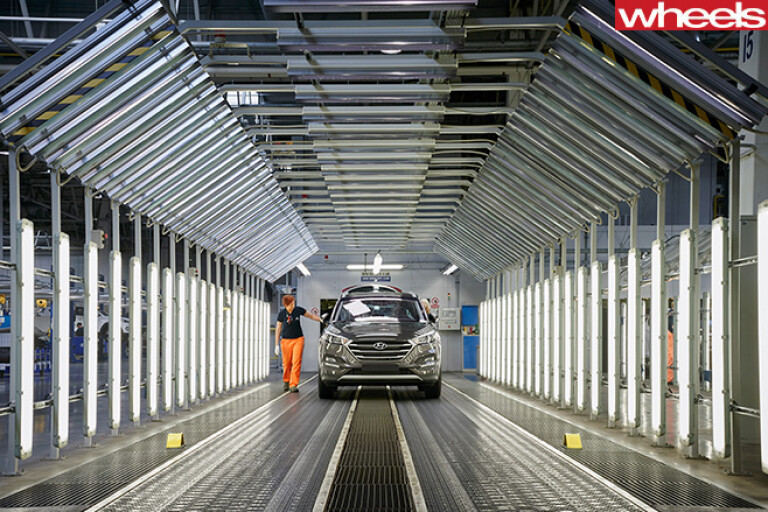

This time around we’ll be the blokes in funny pants and bulletproof shoes helping (supposedly) screw a Tucson together. The idea is to get a taste of what it takes to put a car together, from the stamping of panels at the start to the beginning of its often lengthy journey to its final destination at the other end.

After some death by PowerPoint to learn not to slice our arms off or arm wrestle a robot it’s on with the safety clobber. There are contact sports that don’t require as much gear as those rolling up to assemble a car; steel-capped boots, chunky arm socks, gloves and goggles. Most of it is about protecting me, but some of it – like the gloves – are about ensuring fingernails and rings don’t damage cars yet to find a buyer.

First up is the stamping shop. This is where giant rolls of sheet steel are cut and turned pressed between 30-tonne dies to create everything from bonnets and doors to roofs and boots.

Most of the work is done by gigantic machines pound a piece of metal instantly into a more recognisable shape. The concrete floor shudders as dies weighing 30 tonnes or more are thrust together.

Similarly, the body shop where welding takes place is a sea of 364 robots tasked with taking the basic building blocks and turning them into a shape that resembles a car. Yet people are in place to position the various components so when the sparks fly the bits hopefully stick together.

It’s a tense moment as I hit the big start button that signifies to the machines that all is right to go.

Soon it’s on to final assembly where the bulk of the traditional car building takes place. There are a lot more people and a lot fewer robots.

Trolleys whizz around delivering parts, some as small as bolts, others as large as bumper modules or fuel tanks.

Some of the parts are pre-assembled modules, such as the front headlight and radiator assembly that's screwed on with six bolts on either side.

It’s that fairly important component that I have to bolt on to one of the Australian-spec Tucsons heading towards me. Again, there’s 54 seconds to ensure the bolts are aligned and tight by the time the car is at the next bay. Watching the real workers is an indication of how practised they are at this job … and also a stark wake-up of the monotony that is building cars.

It soon dawns on me there's plenty that could go wrong. Forget a bolt, for example, and it could lead to a failed suspension component half way down the Hume Highway. Pinching an electrical cable could result in windows that refuse to wind. Or just dropping a bolt could lead to a rattle more annoying than Donald Trump trying to make sense. The wrong badge could turn a Tucson into an i30.

Fortunately there are real workers here to watch over me. More than once they explain something to me in broken English. Hand signals and pointing is key at this time.

Part of the challenge is ensuring you’ve got the right part at the right time. Fortunately the entire computer-controlled line does most of that work for you.

The speakers and door trims I’m bolting on are all perfectly aligned to the cars arriving on the production line.

The amount of behind the scenes planning and tracking is bonkers, although humans are still expected to check and double-check the 1s and 0s haven’t got confused along their superhighway.

Yet it’s humans that make most mistakes. About one in 60 cars needs something tweaked, changed or checked before it’s sent for shipping. And almost all of those have that fault as a result of someone overlooking something along what is the ultimate expression of industrial teamwork.

One of the biggest surprises is how much is done at the factory. Even the Australian government-mandated fuel sticker is stuck to the windscreen towards the end of the line rather than on the docks when the car lands.

And the final piece of a very complex car-making puzzle is the addition of eight litres of fuel, four of which is just to fill the fuel lines, with the remaining four just enough to get it from the ship to the showroom.

My Hyundai build experience finishes months later in the Sydney suburb of Macquarie Park at the company’s head office.

We’d hoped to head to the docks to watch the car arrive on one of the enormous RORO ships, but in the end OH&S and regulations got in our way.

Still, having bolted on some numberplates and headed for a brief test drive (the start of which involved some more fuel) I can confidently say there wasn’t anything wrong with ‘my’ Tucson. At least not yet…

COMMENTS