The biggest thrill in driving the Aston Martin DB5 Goldfinger Continuation isn’t channelling your inner Sean Connery, revolving the number plates, firing the machine guns, activating the bullet-proof shield and the rest of the 007 arsenal. No, it’s the fact that you’re driving a 1964 Aston Martin DB5 that’s brand new from its Avon cross-ply tyres up.

The machine guns don’t fire real bullets, it sprays water out the rear rather than oil, and you can’t get rid of a troublesome passenger with an ejector seat. But the DB5 Goldfinger Continuation is a genuine Aston Martin.

It’s made by Aston Martin Works, the company’s in-house classic and restoration shop, at Newport Pagnell – where fewer than 900 DB5s were built between 1963 and 1965 – using parts and components manufactured from original drawings and digital data.

Sliding behind the wheel of the DB5 Goldfinger Continuation and firing up its 4.0-litre straight-six is like tumbling down a wormhole in the space-time continuum.

You half expect to hear a Beatles tune crackling on the radio as you muscle the shifter into first gear, taking care, of course, not to lift the flap on the knob and accidentally thumb the red button hidden underneath.

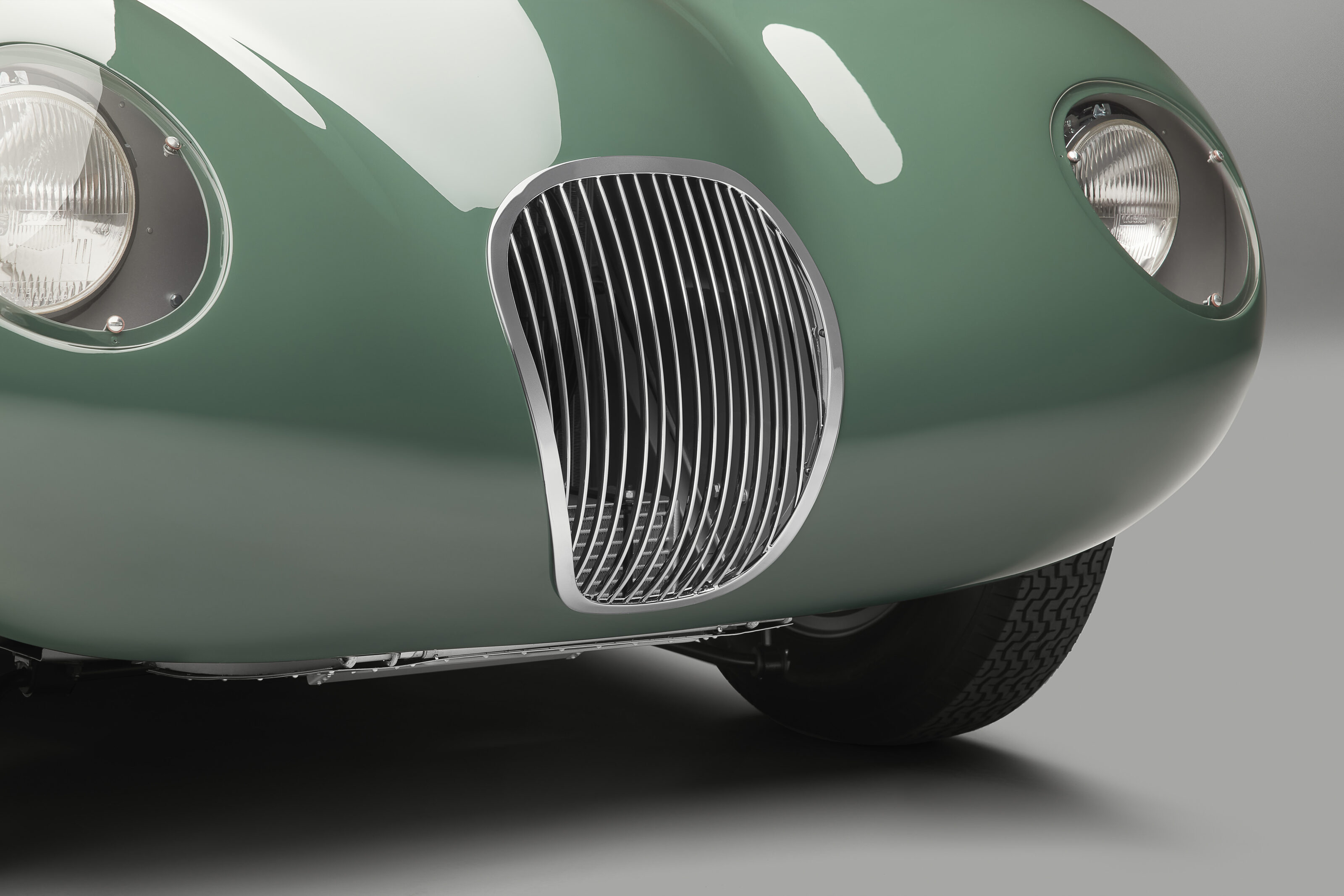

Just 70km up the road, in a quiet workshop on the outskirts of Coventry, Jaguar is hand-building a batch of brand new Le Mans racers.

No, Jag’s not going back to the Circuit de la Sarthe to take on Toyota, Peugeot and Ferrari in this year’s 24 Hour race: these Jaguars are all C-Type Continuations, built to the exact specification of the 1953 works cars that finished first, second, fourth and ninth in that year’s event.

Jaguar Classic engineers consulted original drawings and the original engineering ledger, which contained details of more than 2000 parts, to create a digital 3D model to ensure every component made for the C-Type Continuation was identical to the original.

They even tracked down one of the few qualified arc-welders in the UK so the C-Type Continuation’s tubular steel chassis could be constructed using the same techniques as it was almost 70 years ago.

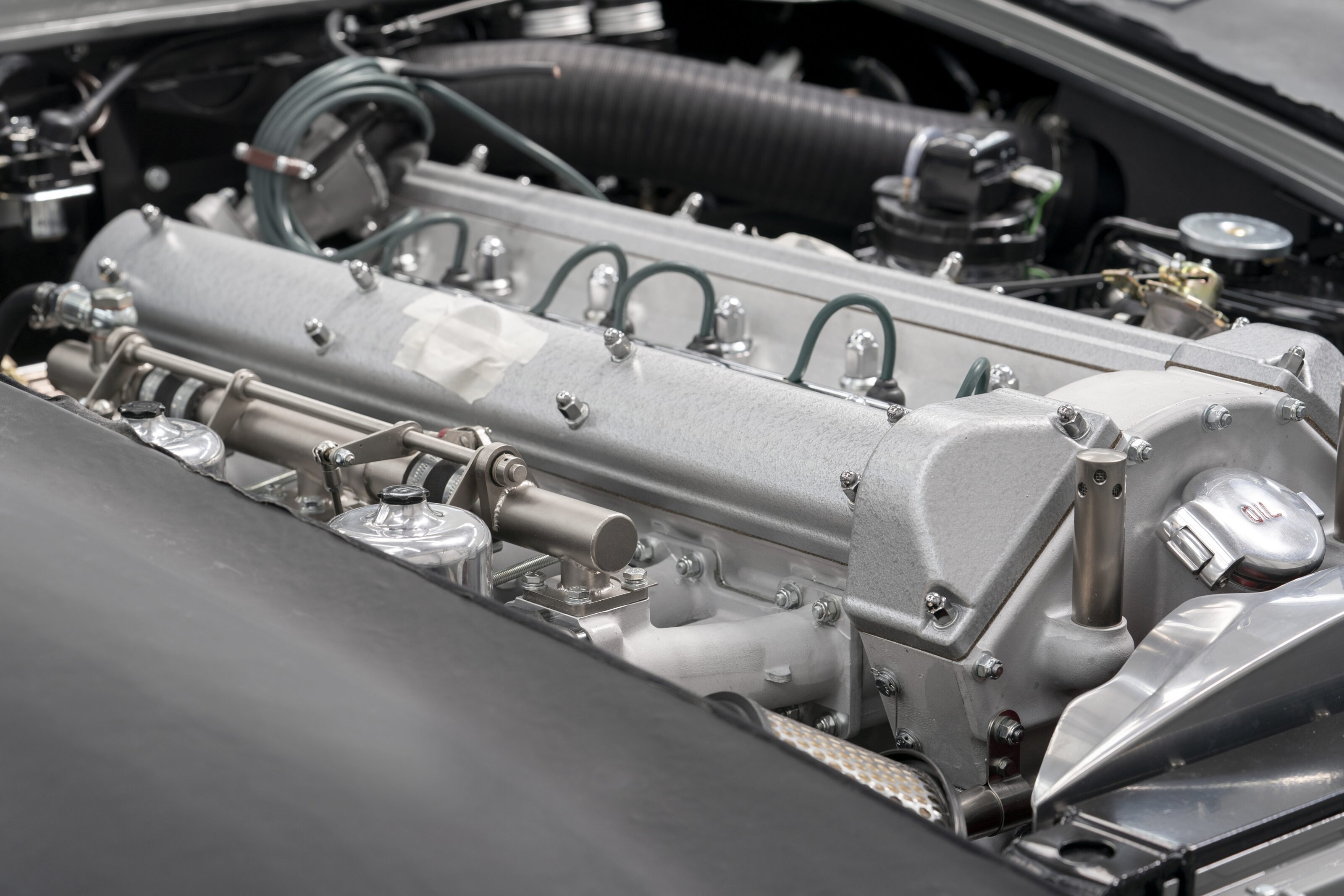

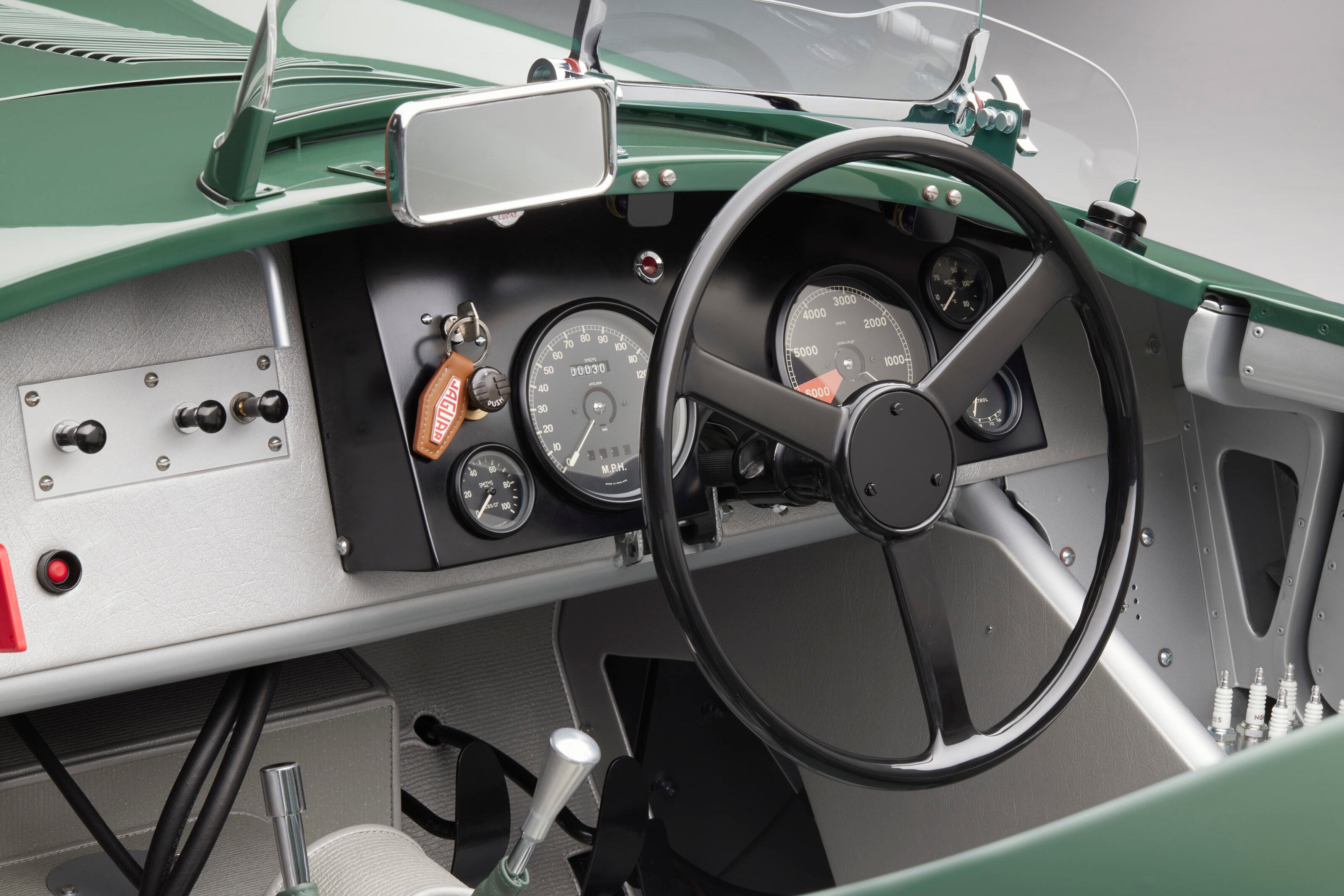

The C-Type Continuation is powered by a remanufactured 3.4-litre version of the famed twin-cam XK straight six that takes nine months to hand-build. The interior features a clock and gauges recreated to original Smiths Instruments specifications.

The period Lucas rear-view mirrors are genuine, and the Rexine artificial leathercloth on the dash and side panels, a material dating back to 1915 and still used by the British Motor Corporation in the 1970s, has been sourced from the last roll in existence.

The DB5 Goldfinger Continuation’s backstory is much the same. ZF’s heritage department built brand new five-speed manual transmissions to the same specification as used in the original DB5s, right down to the gear ratios.

The brakes are identical to the original car’s four-disc Girling set up, as are the telescopic front shocks and old-school lever action units on the rear axle with its mechanical limited-slip differential. British tyre maker Avon made a fresh batch of cross-plies to the exact specification used on DB5s in 1964.

The decision to fit the DB5 Goldfinger with tyres of period-correct construction raised eyebrows among the Aston Martin chassis development drivers, many of whom had never driven a car on old-school cross-ply rubber and struggled with the lack of grip and precision.

But Aston Martin Works boss Paul Spires was adamant the DB5 Goldfinger Continuation not only had to look exactly like it did in 1964; it had to drive exactly as it did in 1964. “It’s supposed to slide and glide,” Spires says. “It’s how the car was back in 1964. We wanted that authentic feel.”

Spires acknowledges radial tyres would have given more grip and precision, but he insists they would also have fundamentally changed the entire car.

“Radials put more load through the suspension and therefore the car rolls more,” he says. “Then you start to slide out of the seats, and the steering feels heavy. It’s easy then to start chasing your tail on chassis set-up trying to fix it and you end up with a car that isn’t authentic.”

Sliding behind the wheel of the DB5 Goldfinger Continuation is like tumbling down a wormhole in the space-time continuum

But for Aston Martin Works, the idea wasn’t just to make the Goldfinger Continuation like new. It’s subtly been made better than new.

Several DB5 bodies were scanned during the early stages of the project and the data reworked by Aston Martin design chief Marek Reichmann’s team to ensure the surfaces were all true and both sides of the body were symmetrical.

Original DB5 chassis were also scanned, and the data overlayed with the 500 original drawings still in the Aston Martin archive to ensure accuracy. The 25 Goldfinger Continuation cars are the most dimensionally accurate and symmetrical DB5s ever built.

An original DB5 engine was put through a high-powered CT scanner and, using a program especially written by Siemens, digitally sliced into one-millimetre slivers so a set of new casting molds could be created.

This allowed engineers to correct an endemic overheating problem in the Tadek Marek-designed straight-six by making sure the cylinder head was cast the way it was originally intended.

Jaguar C-Type Continuation project engineer Dave Moore’s biggest challenge was not only the fact that no definitive factory-spec 1953 C-Type existed – just six were built out of a total C-Type production run of just 53 cars, and all were subsequently modified during their racing careers – but also that there was no record kept as to how the car was originally put together.

“By the time the 1953 Le Mans cars were being built, they had already decided they were going to make the D-Type,” says Moore.

“They didn’t write down how to build this C-Type, because why would they? As soon as the car was finished at Le Mans it was going to be scrapped. All we had was the ledger, written in original ink, which was basically just a list of parts, with their part number and a brief description.”

Any parts brought in from outside were simply noted as such, along with the name of the company that supplied them. “Most of those companies have now gone to the wall, so we couldn’t ask, ‘Have you still got the drawing?’ or ‘How did you make these components?’,” says Moore. “We’ve had to work it out ourselves.”

For example, Jaguar Classic remade the C-Type Continuation’s shocks from the original drawings, interpreting the data to figure out the damper curves. “We have a lot of confidence that car drives as it did in period,” says Moore.

Everything old is new again. It has been for a while. The retro styling trend, which reappropriated and repackaged iconic design cues from ’50s and ’60s vehicles around modern mechanicals, was kicked off by Nissan’s quirky Japanese-market ‘Pike’ cars in the late 1980s – the Be-1, the Pao, the Figaro – and by the late 1990s and early 2000s had crossed over to the automotive mainstream.

Some retro cars were wildly successful: Volkswagen’s New Beetle and Chrysler’s PT Cruiser between them sold more than 3 million units. Fiat’s 500 is still with us, while Ford’s Mustang is on its second retro redesign, and BMW’s Mini its third.

But retro styling is one thing; remaking painstakingly, perfectly rendered versions of cars originally built decades ago is something else entirely. And it’s not just about stroking a corporate ego or polishing brand heritage. It’s business. Good business.

The DB5 Goldfinger Continuation is the third continuation car from Aston Martin Works, following in the wheel tracks of the DB4 GT Continuation and the DB4 GT Zagato Continuation.

The C-Type Continuation is Jaguar Classic’s fourth, joining the D-Type Continuation, the E-Type Lightweight Continuation, and the XKSS Continuation cars. Between them, these cars – just 119 vehicles in total – have generated about $440m in revenue.

Made by the original manufacturers and sold by the original manufacturers, all are certainly more authentic cars than third-party replicas and recreations, no matter how well executed. But are they the real deal?

You might expect serious collectors would be upset that the continuation versions of these cars are being sold at a fraction of the value of vintage originals. But Hans Wurl, a specialist with Gooding and Company, a leading automotive auction house, says those who spend big money on classics are quite accepting of continuation cars.

For some collectors, continuation cars represent an opportunity to drive or race a manufacturer-made car that’s identical to the original one they already own without worrying about negatively impacting the original’s value.

For others they are an opportunity to drive a manufacturer-made car identical to one they’ve long desired to own and perhaps can’t quite afford. “They can have a $10 million experience for $1.5 million,” Wurl says.

Retro styling is one thing; remaking painstakingly, perfectly rendered versions of cars originally built decades ago is something else entirely

Others are happy to see manufacturers actively embracing their heritage for good, pragmatic reasons.

Paul Spires recalls a phone call from an angry owner of a DB4 GT when Aston Martin Works announced the DB4 GT Continuation: “He was really very against it,” Spires recalls.

“I invited him to come and see what we were doing. He said, ‘I was really concerned that you were going to do a cheap, nasty car and make as much money as you can, but what you’ve done is actually better than my car. And I’ve now seen that some of the componentry on my car is coming towards the end of its life, I can buy new parts’.”

For all that, Hans Wurl says most serious collectors believe that no continuation car, no matter how faithful its recreation, will ever have the same value as a vintage original.

“Provenance and history add value,” Wurl says, “and most serious collectors are motivated by the provenance and history of their classic cars. They want to sit in a car that’s 60 or 70 years old.”

Wurl says that although Jaguar and Aston Martin have done the right thing by strictly limiting the number of continuation cars they build, they will never appreciate at the same rate as the originals, at least in the short to medium term. And in the long term?

“As we get 50 to 100 years down the road, there needs to be clear delineation between the continuation cars and the originals,” Wurl insists. “And it’s up to the collector car community to make sure that happens.”

Jaguar and Aston Martin have proven the past can be profitably brought back to life. But the problem for both companies now is: What next?

They have each already built the most obvious superstars from their back catalogues, cars that could justify multi-million-dollar investments in parts and labour by commanding seven-figure price tags.

And as all are cars from simpler times – times before plastic interiors and on-board computers and catalytic converters and stringent crash safety regulations – they have all been relatively straightforward to build.

For Jaguar and Aston Martin at least, playing the continuation game gets a lot trickier from here on in.

Dave Moore reckons one option for Jaguar Classic might be to build a brand-new XJR-9, the V12 Group C racer that won the 1988 Le Mans 24 Hour. Or remake what Jaguar insiders reverently call “The Holy Grail”, the one-of-a-kind Jaguar XJ13 Le Mans prototype from the 1960s.

“It’s not a plan we’ve ever discussed if I’m honest,” he admits of the XJ13 idea. “We’ve got the car in the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust collection, and we always look at it and think, ‘that would be really cool to do’.”

Like Jaguar, Aston Martin could look back to 1950s Le Mans racers and consider making continuation versions of its DBR1, one of which, driven by Carroll Shelby and Roy Salvadori, took victory in the 1959 24 Hour.

The same process that resulted in the DB5 Goldfinger could be used to produce continuation versions of the rarest DB6s, such as the Volante Vantage with the ‘C stage’ triple Weber straight six under the bonnet – just 13 were ever built – or a DB6 Vantage Shooting Brake. Just six DB6 Shooting Brakes were made, and a Vantage version recently sold for more than $1.4 million.

“We have a whole cycle plan of continuation cars,” says Paul Spires, though he refuses to be drawn on detail. “Unlike the heritage arms of some other OEMs, this place has to be commercially viable. We don’t do these things just because we want to. We have to look after our heritage.”

Closer look: Snake’s second bite

A new cobra better than the original

Storied British manufacturers like Aston and Jaguar aren’t the first ones to reap the spoils of the continuation movement. Shelby Cars also saw the opportunity to build the famed Cobra sports car as a continuation of the original which went out of production in 1967.

Produced in Las Vegas, Nevada, these cars didn’t follow the blueprint for 100 percent originality the way the Jaguar and Aston models do, having the appearance of their original 1960s ancestors, but tweaked for more reliable performance.

We recommend

-

Reviews

Reviews2017 Aston Martin DB4 GT Continuation review

Faithful, modern recreations built to original Lightweight specification for a lucky few

-

News

NewsA rare, brand-new Aston Martin DB5 'Goldfinger Continuation' is set for auction

One of the first Aston Martin DB5 models built in more than 50 years is set to go under the hammer, with a hefty final price expected

-

Features

FeaturesContinuation Cars: Is the Nostalgia-trip really worth it?

Talking about old cars has one purpose: to reflect glory on the new ones that companies make money on.