They emit only water, refuel in three minutes, and you can buy one in Japan. So why aren’t they here?

AUSTRALIA is at something of a crossroad when it comes to what will power our cars when fossil fuels eventually run out.

In the words of Federal Industry Minister Ian Macfarlane, the safe bet from some manufacturers – electric cars – is not the way of the future.

“The reality is that if you drive an electric car, the chances are it’s being fuelled by fossil fuel-generated electricity,” Macfarlane said recently. “Outside that, it’s an idea, not a solution.”

Macfarlane has hinted that Australia’s path to fossil fuel freedom will be via hydrogen, an element that is readily available and easily generated using nothing but sunlight.

Why, then, aren’t the carmakers rushing to fill the hydrogen-fuelled void?

Compared with Japan, the US and Europe, where it’s already possible to drive long distances using hydrogen fuel, Australia has a lot of catching up to do.

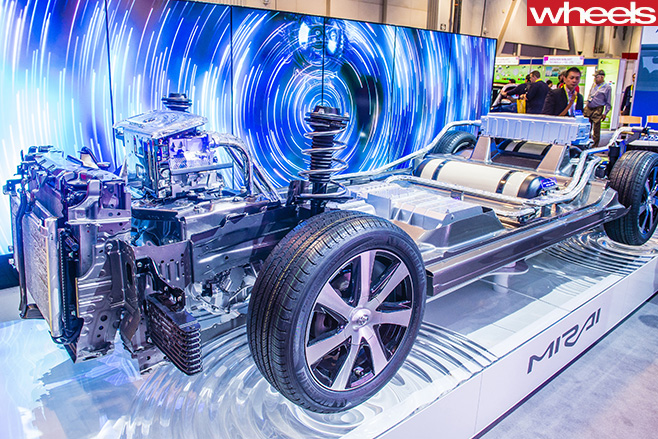

However Toyota’s Executive Director of Sales and Marketing, Tony Cramb, said the brand had “no plans” to sell the Mirai here, even though it had brought the car to Australia in October last year, to coincide with the World Hydrogen Technology Convention.

The idea had been to “start the conversation with some of the key stakeholders, to try to get the infrastructure in place,” Cramb said.

Toyota’s wait-and-see approach contrasts starkly with that of Hyundai, which is gaining traction with government via a fuel cell-powered ix35 SUV running around our roads.

The futuristic-looking Toyota Mirai is also the world’s first commercially available hydrogen fuel cell vehicle. It is on sale overseas for the equivalent of $108,000.

Hyundai’s more conventional-looking ix35 Fuel Cell is the Korean company’s fourth-gen FCV. The next gen version will be mass produced in both left-hand and right-hand drive, putting Australia firmly on the map as a potential market.

Hydrogen fuel cells are already in use in buses and forklifts, and in non-auto applications such as back-up generators for mobile phone towers. How large a piece of the sustainable motoring puzzle the technology will contribute remains to be seen, but brands such as Honda, Volkswagen, BMW and Mercedes-Benz are all on board.

“In Australia, we’ve got the best environment to be able to do things in a cleaner way – as in solar and wind,” Hyundai’s Nargar said.

The challenge in making hydrogen mainstream is not with producing the gas, but distributing it – setting up places where the drivers of hydrogen cars can refuel. Even the experts are not certain how such infrastructure will roll out in Australia.

One model is built on setting up refuelling depots at, say, bus or courier companies, or for a fleet of government or corporate cars. A hydrogen highway linking cities such as Sydney and Melbourne via the calculated placement of hydrogen-enabled fuel stations would make fuel-cell cars viable for some private buyers.

For now, the refueller at Hyundai’s headquarters at Sydney suburb Macquarie Park is quite possibly your nearest servo.

“It’s open to any manufacturer who wants to use it,” says Nargar, typifying the spirit of cooperation between the brands.

“You’re splitting the smallest element into its H-plus ion and an electron at a rate of a billion times a second in your vehicle,” explains hydrogen expert Cranston Polson.

However, the rest of the modern fuel cell vehicle is decidedly – and deliberately – normal. For example, it takes about three minutes to refillo the tank, which typically holds about 6kg of hydrogen at high pressure. Filling up with hydrogen is as easy as filling with LPG.

Range officially totals 550km in the Mirai and 594km in the ix35 Fuel Cell. The service interval is in the realm of conventional cars, and the cost is likely to be lower than anything with an engine.

Hydrogen has a low atomic weight – it’s lighter than air – so it diffuses quickly into the atmosphere rather than forming explosive concentrations.

The experience of driving a fuel cell vehicle won’t confront anyone who has driven a hybrid or electric car – as our drives of the Hyundai ix35 Fuel Cell and Honda Clarity Fuel Cell late last year made clear. Although they do have some curious features – such as the H2O button on the Mirai, which prompts it to take a leak on the street before coming inside.

Taste the technology and it occurs that the question is when – not whether – hydrogen will make an impression in Australia. Hyundai’s next-gen FCV could be here within three years.

What’s inside a fuel cell? That’s secret

THE grapevine has gone quiet on the materials inside the modern fuel cell. “Discussion on that just completely dropped off,” says hydrogen expert Cranston Polson of H2H Energy, who is working with Hyundai Australia. The fact that R&D has shifted from universities into company IPs is a sure sign that commercialisation is in full swing.

“They could be using low-density platinum, or another material all together,” says Polson.

The Toyota Mirai costs more than $100,000 in Japan, but price reductions will come with volume production, and from the further development and in-house manufacture of fuel cell membranes and hydrogen tanks.