Renewably manufactured synthetic ‘fossil fuels’ could save the internal combustion engine, keep classic cars on the road for generations to come and more rapidly achieve the holy grail of net-zero global carbon emissions – all while preserving the noise and thrill of petrol-powered motorsport all over the world, well into this century.

Dubbed ‘eFuel’ and attracting significant investment from the likes of Porsche, Bentley, Ferrari and more, synthetic fuels rely on renewable energy to power electrolysis that takes hydrogen from water and combines it with carbon captured from the atmosphere.

A complex and expensive process, when refined into a green ‘petrol’ and burned in an internal-combustion engine, theoretically no carbon is released into the atmosphere that wasn’t there before.

That’s opposed to, of course, burning products from crude oil that’s been in the ground for millions of years. With eFuels’ simpler chemistry, the result is also a cleaner burn with fewer tailpipe nasties – and a fuel that utilises well-established, existing supply chain infrastructure geared around liquid energy.

New eFuels could also keep millions of internal-combustion vehicles on the road, as opposed to discarding them for brand-new electric equivalents, potentially saving a few million tonnes of manufacturing-related carbon emissions all on its own.

Another advantage of eFuels is opening opportunities and gaining flexibility often lacking with renewable power. Porsche, for example, has teamed with Siemens Energy and a global consortium to build an eFuels plant in Punta Arenas in Chile.

This remote part of South America is like a Middle East of renewable energy, but therein lies the problem – like many renewable hotspots on the earth, it’s in the middle of nowhere. By using its almost unlimited and dependable wind power, eFuels can be reliably manufactured but then easily transported all around the world – including to nations not blessed with the same natural renewable energy resources as others.

Porsche has mentioned Australia, as well, as being a candidate nation for an eFuels plant, taking advantage of the almost limitless solar energy beamed reliably on to the Great Southern Land every single day.

Dense with energy, synthetic fuels can also almost be thought of as another form of battery. Sometimes, of course, the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine. It’s cheaper to store energy as a liquid than in a giant lithium-ion mega battery. And in theory, great swathes of Australia could be covered in solar farms, the energy exported easily in liquid eFuel form.

So if it’s as great as it all sounds, why aren’t we cracking into it? Of course, as is always the case with these things, there are major hurdles with eFuels – the first being they are at present frightfully expensive to produce. The dream is to reach price parity or undercut fossil fuels on a cost-per-litre basis, but there’s a long way to go before the necessary economies of scales are realised.

Currently one litre of eFuel is about A$13.50, meaning to fill a 50-litre tank would cost about $700. Porsche says it expects the cost of eFuel to reach closer to A$2.75/litre by the end of this decade. The Chilean plant is expected to produce 130,000 litres of eFuel this year, scaling up significantly to 550 million litres by 2026.

There are other problems, too, however. Manufacturing eFuels with renewable energy doesn’t pass the greater sniff test (although they are said to smell a lot nicer than petrol). From wind turbine to, say, creating momentum with an internal combustion car, eFuels can’t compete with a battery electric vehicle (BEV) for efficiency – meaning they are unlikely to ever end up as the primary energy source for the great unwashed.

A 2020 study from the Society of Automotive Engineers found just 6-18 percent of the original energy captured renewably, made it to the wheels for an eFuel-powered combustion vehicle; versus 40-70 percent for a BEV. In fact, it would make more sense to use the renewable energy to manufacture green hydrogen to be used in a Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (FCEV) which is more like 23-33 percent efficient.

And from a broader decarbonisation perspective, we need all the renewable energy we can get, deployed as efficiently and effectively as possible. Using it to produce eFuels doesn’t make sense next to replacing a carbon-billowing, coal-fired power station.

Instead, eFuels remind us that rapidly decarbonising the entire world requires an enormous suite of solutions. It’s going to be a very long time before we see a battery-powered Boeing 737; eFuels could eliminate the 12 percent of global emissions currently produced by aviation, relatively easily and quickly. But also keep that E46 M3 of yours bolting up twisty country roads for a long time to come.

STUTTGART’s GREEN burn

Porsche is spending big on eFuels as it tries to reach ‘carbon neutrality’ for itself by 2030. That means mostly transitioning to electric vehicles (and betting they will be recharged by growing quantities of renewable energy).

Down the track, at the factory, brand-new combustion cars are planned to be filled for the first time with renewable eFuel, while eFuel will also be used for Porsche’s driver experience events.

The German marque is also keeping classics in mind, with up to “70 percent” of all Porsche sports cars ever built still being on the road today. Meanwhile the first batches of ‘green’ synthetic eFuel from Chile will be used to power the Porsche Supercup championship in Europe as early as this year.

01

Synthetic fuels are artificially created hydrocarbons. Using electrolysis, hydrogen is extracted from water; and then combined with carbon ideally taken from the atmosphere.

02

That means eFuels are sort of like carbon capture. By then burning an eFuel, no new CO2 is being released into the atmosphere – it’s carbon ‘neutral’.

03

We’ve glossed over a lot of chemistry here, but the entire process must be powered by renewable energy. It makes no sense to burn fossil fuels to create eFuels.

04

Synthetic fuels burn ‘cleaner’ with less NOx and particulates. They can be blended with existing petrol; or refined to run in existing cars with no retrofitting whatsoever.

We recommend

-

News

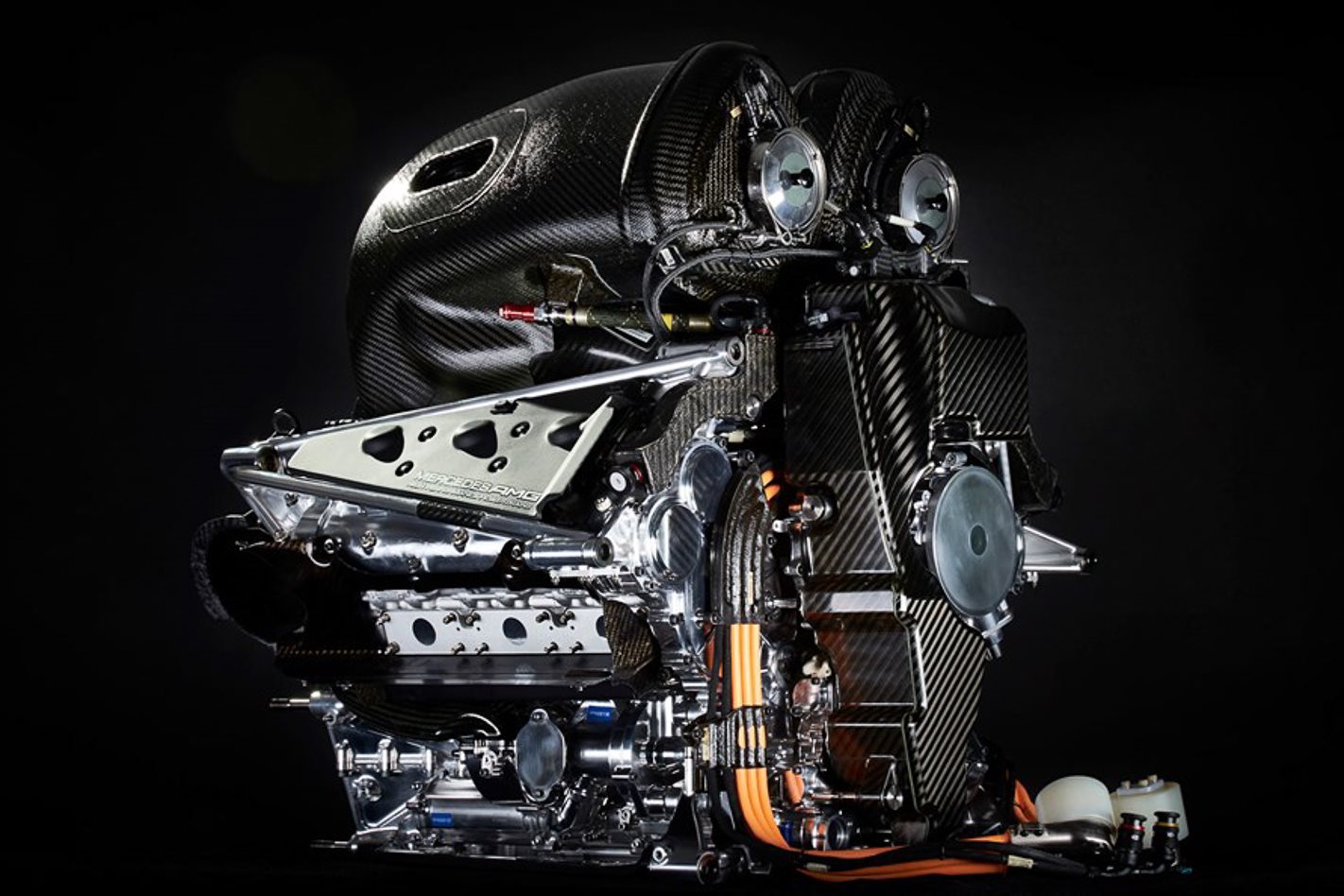

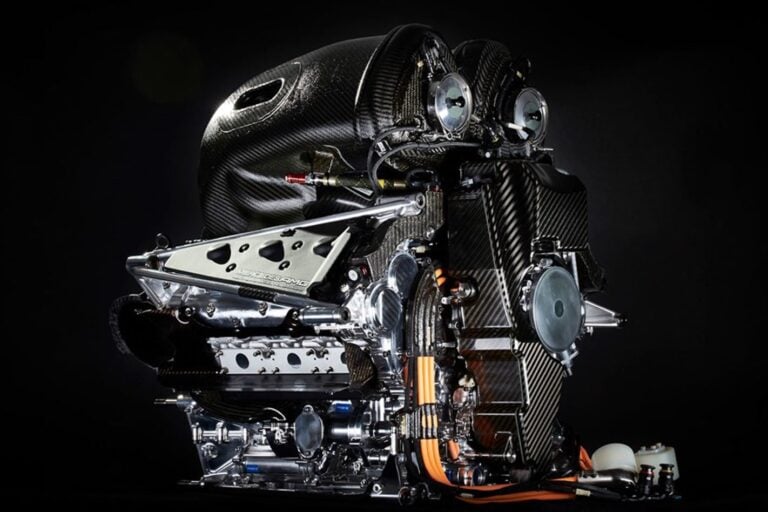

NewsFIA develops sustainable biofuel to power F1 engines

The new 'proof of concept' is a part of the sport's pledge to be more sustainable

-

News

News$500 million diesel and biofuel refinery to be built in Queensland

Queensland's fuel industry is booming, with projects worth billions headed for its doorstep

-

News

NewsWhy NZ's Clean Car Standard is bad news for some carmakers

As well as making EVs and hybrids cheaper, New Zealand's Clean Car Bill will see fees imposed on higher emitting vehicles. So where does that leave brands with no EVs?