FORTY years after the biggest Ford track moment ever – the Falcon one-two at Bathurst – the once secretive, private and focussed Allan Moffat finally lifts the lid on the juicy and mysterious stuff in a stunning if divisive career.

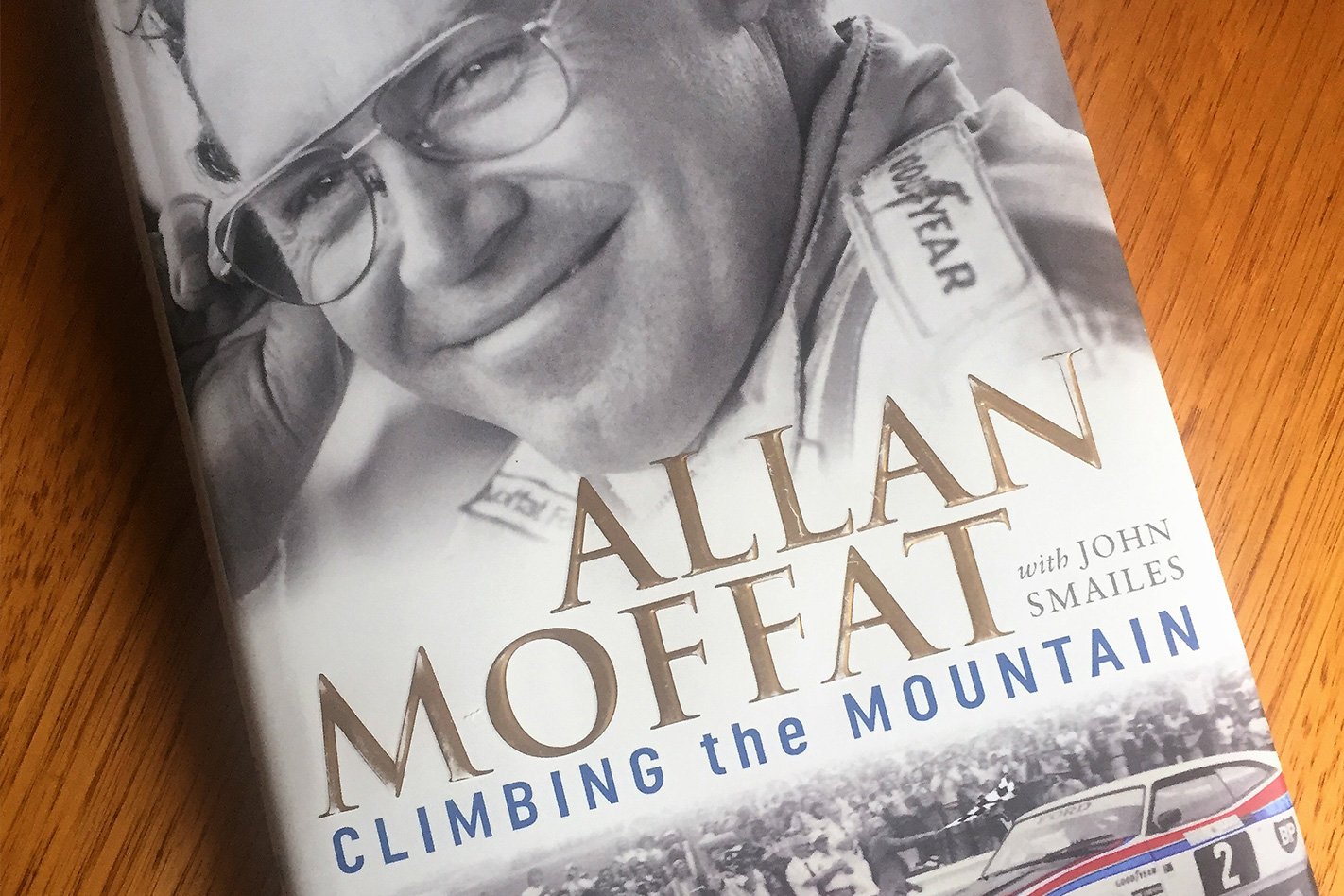

His revealing new autobiography, Climbing the Mountain, co-authored by John Smailes, is a serious page turner.

Through the 1970s Ford and Holden wanted to milk the benefits of racing success while also appeasing politicians and activists.

While a car company’s reputation and image back then were built around performance models, political pressure and a changing, softer corporate ethic pushed Ford Australia to officially withdraw from motor sport in 1974.

The company continued to support its hero driver Allan Moffat through the back door (via the Moffat Ford Dealers Team) but the money wasn’t abundant.

“It was completely hand to mouth, and it was a difficult time … with factions inside the company forever questioning my value to the corporation,” reads Moffat’s new book.

Then came one of the more unforgettable moments in Australian motor sport – perhaps the most memorable for Ford supporters – the crushing Moffat-Bond one-two in the ‘77 Bathurst 1000.

This was orchestrated by the bespectacled Canadian that Edsel B. Ford II once described as “the most driven white man I’ve ever met“.

Even in the early days after he had secured a works Lotus Cortina for the 1964 Sandown Six Hour, Moffat continued to carefully forge relations with overseas teams that might help him climb the greasy pole. Hence he was Jim Clark’s water boy at the 1965 Indy 500, holding out a cup at the end of a broomstick during pit stops. Another remarkable factoid from the book.

After the crushing 1977 Bathurst double whammy, Moffat sensed that Ford would be eternally grateful and was delighted to receive a summons to Broadmeadows for a boardroom lunch two days later. This would be the thankyou from the big boss Sir Brian Inglis and the hard-to-like marketing chief Max Gransden. Sir Brian delivered a wonderfully positive speech spelling out Ford’s gratitude to Moffat and his role in the “Win Sunday; sell Monday” sales fight.

Then he handed Moffat a sealed envelope. Payday! Moffat was thinking $50,000 or maybe $100,000 to reinforce his Ford future.

Later, in the car park, he opened the envelope. The cheque was for $1000. Tight-arsed Ford’s Bathurst-win bonus didn’t even cover Moffat’s post-race party. It certainly didn’t cover the later court action from the Bond camp.

One of the most private and introspective people in motor racing, Moffat – with some steady prodding from Smailes, has at the age of 77, finally opened up on much of the shenanigans behind the scenes, as well as his ongoing dislike for some of the big names of the sport.

Judging by the anecdotes across the 440 pages, Moffat is a good hater. Forgiving is not a part of his credo. Bob Jane cops plenty, as does Norm Beechey. The ongoing rancour directed at his old rivals is sheeted to the ferociously hard muscle-car racing of the 1970s where close battles were sometimes concluded with a deliberate fender bender.

The Moffat of that era was tough, fearless and fast, happy to dish out the biffo when required.

He offers regrets that he didn’t keep some of the cars that once sat in his workshop in Toorak. The Mustang and the Cologne Capri RS3100 went for comparative peanuts in light of their worth today.

Moffat also serves it up to some of his own co-drivers including Bobby Rahal, who at Le Mans apparently didn’t share a priority at for mechanical sympathy and blew the engine in their Porsche 935 when running fourth. Many of Moffat’s co-drivers, including Gregg Hansford and Jacky Ickx, are highly regarded though.

Moffat has particular praise for the sportsmanship of Murray Carter who lent him his Falcon after a thief stole his. And John Goss too, offered up his car after Moffat’s was destroyed in a fire.

Harry Firth is acclaimed as a driver by Moffat but fails to elicit the same admiration as a Ford team boss. Firth always claimed he walked away from Ford to join Holden. The truth, says Al Turner, the US executive imported to fire-up Ford’s local motor sporting operations, was that Firth and he didn’t see eye to eye. “I called him in and told him we no longer needed his services,” Turner is quoted as saying in the book.

Moffat also rips into Howard Marsden, another local chief of Ford’s factory effort and later to run Datsun’s rallying and touring car campaigns. Though acknowledging the Englishman did build a sensational Phase III Falcon, Moffat condemns the pukka Marsden as a “yes” man who didn’t fight near hard enough to keep Ford in racing.

First impressions clearly mean a lot with Moffat, who recounts his first meeting with a giant of American racing at the office of Goodyear Racing’s Mike Truesdale in Akron. Another visitor arrives, shoves Moffat on the arm to move him aside and starts talking to Truesdale as if Allan didn’t exist. It was Roger Penske. “I know these days Penske has a god-like reputation and the patina of a sweet guy about him. But first impressions count.” Good acts or bad acts, Moffat doesn’t forget.

More surprising to many, are revelations about Moffat’s own complicated personal life. You’d be dead wrong if you thought that Allan George Moffat, as focussed as he was on staying afloat and, ultimately, winning, didn’t have the time or energy for the fairer sex. Wife Pauline, who was a fixture in the Moffat pit in the early years, discovered she’d been replaced in the driver’s affections by the younger Sue McCure, who went from fan to Allan’s secretary to his lover in quick time. This development resulted in sons James and Andrew, born less than 15 months apart to different mothers.

It’s impossible to know exactly how much Moffat has revealed of his private life and the often weird machinations of motor sport. Plenty perhaps. Smailes has certainly managed to prise open the vault lurking between Moffat’s ears. As a result the reader better knows the extent of his, uncompromising and driven nature.

This complex, sometimes aloof, proud and emotional individual is an intriguing dude.

While Moffat was one of first real pros of local motor racing and an acknowledged expert at securing and keeping sponsors, his was also an ongoing struggle to find the funding to compete at the top level against rivals who sometimes enjoyed generous budgets.

The 1980 Bathurst 1000 was the last time Moffat drove a Ford Falcon at Mount Panorama. Early into that race, an emerging driver named Dick Johnson had clouted a rock and ricocheted into the consciousness of Australian Ford fans, and on to the radar of Edsel B. Ford II.

Moffat had read the tea leaves and well before then had been looking at other opportunities outside Ford.

He went after a BMW factory connection but was crushed when Frank Gardner pulled off the deal for Australia. The silver lining though was that Moffat then investigated and wooed Mazda. This was to be the most satisfying and rewarding relationship in his career, even though he couldn’t turn an RX-7 into a Bathurst winner.

Then came the shock love-in with Peter Brock and his Holden team. When Holden pushed its star aside over the energy polarizer, Brock was left almost broke and ex-employees Moffat and John Harvey used a front man to buy a new, unraced 05 Commodore to use in Europe in 1987.

But Moffat then delighted the Ford fans with his return to Ford machinery, the Group A Sierra RS, to see out his career.

That career will by any measure be judged a stunning success. He won the Australian Touring Car Championship four times, the Sandown 500 six times, the Bathurst 500/1000 four times. Internationally, he won the Sebring 12 Hour and, with Harvey, the opening round of the inaugural 1987 World Touring Car Championship. His last hurrah was winning the 1989 Fuji 500 in Japan at the age of 50. Then, with no fanfare, he walked away.

Writer Smailes has worked miracles to somehow encourage Moffat to open up and enter the virgin territory of self-analysis: “There may have been people with more money, better support, and, yes, I admit it, greater driving talent. But no-one had a greater, unrelenting, driving dedication to achieving his goals.”

Hard to argue.

Climbing the Mountain, by Allan Moffat with John Smailes is published by Allen & Unwin and is available in all good book stores priced at $39.99.