IN 1995, Porsche was a basket case. No, really. In the entire fiscal year, it sold 19,262 cars.

That’s what the Dongfeng Fengxing Jingyi SUV (nope, us neither) sells in about two months in China alone.

Last year, Porsche shifted a record 237,778 units, a rise of 1234% from its 1995 nadir. Its half-yearly progress report suggested it’s easily on target to sell more than a quarter of a million cars in 2017. In terms of money made per unit produced, Porsche is one of the most profitable car companies in the world. So what happened?

It probably won’t have escaped you that 1995 was the year before the Boxster went on sale. Porsche’s model range consisted of the tired 968, the nearly dead 928 and the last of the air-cooled 911s. For all the reverence that the 993-generation 911 is held in today, back in ’95 it felt archaic and sales reflected that.

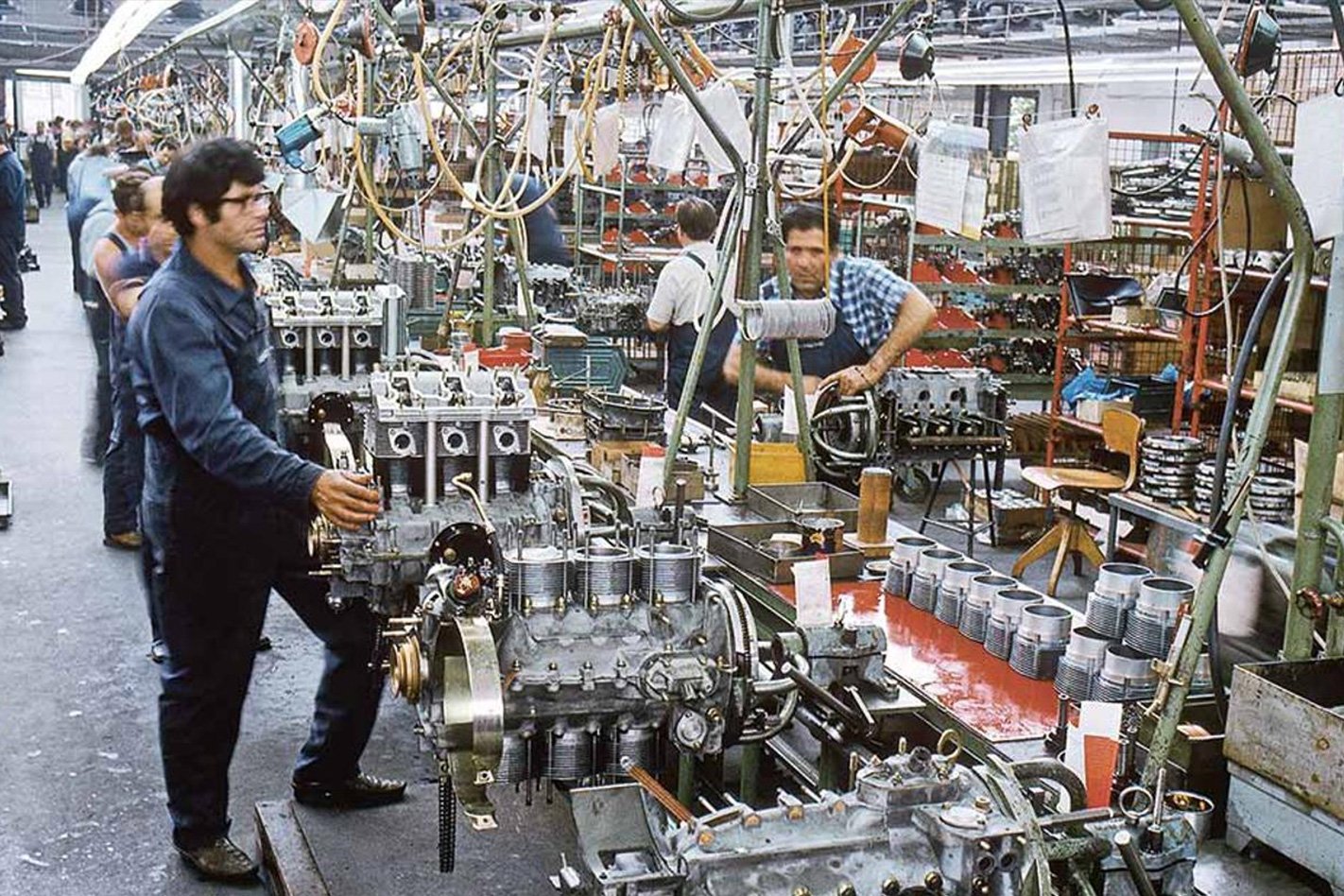

The 993 found around 5,500 buyers that year. In other words Porsche’s core model range was selling 20 units per day worldwide. That’s unsustainable. And Porsche’s manufacturing process was an absolute shambles. According to a 1996 New York Times story, engineers would have to rifle through parts bins and climb ladders to search shelves to build a single car.

Porsche turned to Toyota for help. The Japanese analysed Porsche’s processes and instituted a series of ‘just in time’ production methods. Procurement procedures were sharpened up and a more direct focus was put on reducing the cost of build.

Porsche claims it slashed the assembly time for one car from 120 hours to 72, and the number of errors per car had fallen by 50 percent. Building parts commonality between the 996-generation 911 and Boxster also hugely increased the profitability of the latter car but at a price.

Porsche cut corners everywhere to reduce the cost of construction. The 996 was, in terms of build quality, a poor car. The engine design was fundamentally flawed, with a litany of failures from oil leakage at the rear main seal to cylinder head failure. Porsche blithely ignored stories of porous engine blocks and intermediate shaft failures in a terrible corporate failure of denial and obfuscation.

And the huge revenues it earned helped pay for the development of the second golden egg-laying goose, the Cayenne SUV. You probably know the Cayenne story already, so we’ll press fast forward.

In 2015, Macan and Cayenne accounted for 68 percent of sales. Porsche is now an SUV company that makes a few sports cars on the side. The Macan, a model that didn’t exist one year previously, represented a third of Porsche’s sales. Think about that for a moment. Those are all conquest sales, registrations that come straight out of BMW, Mercedes and Volvo’s bottom line. Or, if you’re a little more cynical, result in a bit of internecine cannibalism from VW Group siblings Audi.

News outlet Bloomberg reported last year that Porsche profited by more than A$23,000 on every car it sold. That figure’s derived from a reported operating profit of A$5.75 billion (€3.9 billion) divided by sales. Compare that to BMW and Mercedes-Benz, who make about A$6500 per vehicle from sales around the world.

Okay, so Porsche still has a way to go to equal the A$118,000 per vehicle that Ferrari makes, but around a third of Ferrari’s profits actually come from merchandising, theme parks, spare parts sales and sporting sponsorships.

So Zuffenhausen continues to grow fat, basking in the largesse of buyers who can’t get enough of its vehicles. The Chinese market is booming for Macan and Cayenne, while sales of the new Panamera leaped by 54 percent year on year. One of the hidden effects of this shift to larger cars is that the vehicle that saved Porsche from bankruptcy, the Boxster, now occupies one of its most specialist niches. Just 12,848 Boxsters found new owners in 2016, representing only 5.4 percent of Porsche’s sales.

Porsche probably doesn’t mind. Its motorsport endeavours still present a sheen of pure-bred credibility and those enormous SUV sales fund ever more magnificent sports cars. But spare a thought for a time not so very long ago when the company was less a paragon of German efficiency and more a case study of inept management. If Porsche can turn around in this manner, perhaps it’s not beyond some of today’s strugglers to do likewise.