Who is responsible in the event of an autonomous car having a crash – the driver or vehicle itself – was at the forefront of a leading industry event held in Melbourne this week.

A panel of experts at the Autonomous Vehicle Technology Conference (APAC21) discussed the major safety issue facing the industry and lawmakers alike, with attendees keen to hear the answer.

Speaking during the event’s trials, policy and regulation panel, James Hurnall, Director of Policy at crash test authority ANCAP, said the issue was being looked at closely by the industry and others.

“I know this is an important question that's been looked at what we call ‘highly automated vehicles’ – vehicles operating at level three or above,” he said.

“What is important is whether the vehicle is in control at that point in time [in a crash]. There’s a concept called automated ADC, an entity that will be responsible for the vehicle when it's operating in an automated mode. That's my understanding.

“I understand the car companies are looking at how to do that [how to differentiate between car and driver] as well and uh, then it becomes very important also with whether it's an OEM product or an aftermarket product, because that then becomes really difficult with how to handle it.”

Samantha Cockfield, Head of Road Safety at the TAC, added that for her organisation the issue was less consequential as the TAC ensures the vehicle rather than the individual already.

“For the TAC we actually ensure a vehicle not an individual. So the issue of you know, who's in charge, doesn't matter quite as much. But I think at any point where the driver still has control, you've really got to say that the driver still has to actually be the end point for it,” she said.

“But, I mean, we really are looking at the timing and particularly, as an insurance scheme, to be working with manufacturers rather than individual drivers in relation to fault.”

At the conference, representatives of Ford Australia’s ADAS division (Advanced Driver Assistance System) asked about what would be done in scenarios where people overestimated the capabilities of lower level AV systems and whether it would lead to an increase in road accidents, referring to recent examples in the US where drivers were found trying to trick the car into believing a human being was still in control when they weren’t.

Responding to the concerns, Cockfield said: “I think, you know, as long as I've been human safety, which is around 30 years, where I've talked about vehicle technologies coming in, that people will just assume that the car can do more than it can. It happened with ABS when that was introduced too.”

“We're certainly going to need some education enforcement,” said Harnall. “As we do with the introduction of any technology. Let's not let that blind us to all those benefits that we can potentially get because of a couple of bad cases. What we are looking at in our rating system is what information is provided to the driver, how they remain engaged with the vehicle.

“So it's how the vehicle, how the manufacturer promotes and names the system, how the information's provided to the driver or the vehicle owner, and then how the vehicle owner continues to be engaged in system. At the moment we're assessing drive monitoring systems, which basically is assessing how well the vehicle ensures the driver is still engaged.

“I picked up a new car three weeks’ ago and as I was driving home, I was playing with the touchscreen and the next thing I know it says to me, ‘you're not paying attention, do you want to pull over if you’re tired?’ So that technology is there and to help the people that are making a genuine mistake. There are people who are going to go out of the way to defeat the system, same as we have now in that people are going out of their way to speed or to drive with alcohol in their system.”

Over the last few years, the National Transport Commission (NTC) which is tasked with leading a range of transport reforms on behalf of jurisdictions across Australia, has been working on a complete end-to-end overhaul of regulation on this topic – which involves untangling more than 700 existing laws.

Although there is no exact end date in sight for this work to be wrapped up, the NTC says it is well on track and in July this year published a discussion paper on the sub-issue of the powers of law enforcement to interact with and respond to the road safety risks of automated vehicles. Earlier this year, transport ministers across the country made an agreement to start drafting new legislation by the end of this year, with a view of a national law being put into effect by 2026.

It’s worth noting other countries are at different stages of developing regulations for automated vehicles, but no jurisdiction has a complete system of regulation as yet.

It’s expected, based on research being carried out by the NTC in recent years, that the new national law will establish that the automated driving system entity (ADSE) is legally in control of a vehicle when automated functions are operating – but that the fallback-ready user should remain sufficiently vigilant to respond to requests and failures, and regain control when required.

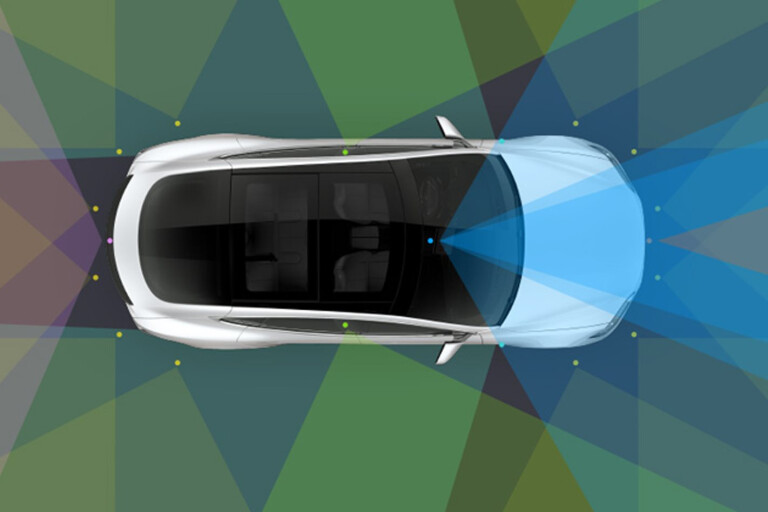

Currently there are five levels of autonomous driving. Under level one, the car just accelerates or brakes for you but you remain completely in control, such as with cruise control. In level two, it’s much the same but slightly advanced, such as automated reverse parking and again you’re in charge and needs to react to the environment.

By level three things get interesting, which is where much of this debate starts to become relevant. The vehicle does everything for you but only under certain conditions such as a certain speed, weather or time of day and a driver must be capable of taking over straight away when requested. Level four is similar, but the human does nothing while the car is travelling and only needs to take responsibility at other times.

Full automation comes at level five, which means the car does everything the person does zilch.

Other issues raised at the conference surrounded addressing the ongoing safety of ADS throughout a vehicle’s lifetime and who is responsible for that, and how it impacts car insurance claims.

Again, the NTC is developing reform to enable people injured or killed in a crash involving an automated vehicle to access an equivalent level of care, treatment, benefits and compensation to that experienced by those involving a vehicle crash controlled by a human driver.

Transport ministers agreed in August 2019 on a national approach to insurance for automated vehicles that requires existing motor accident injury insurance schemes to provide cover for automated vehicle crash injuries. Ministers were asked to join a working group considering the policy issues and will report back on progress.

COMMENTS