TOYOTA Motor Corporation has inked a three-year joint research agreement with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to collaborate on the development of a manned, pressurised lunar rover.

The announcement comes four months after JAXA, together with Toyota, stated its intention to create a hydrogen-powered wheeled vehicle to cross the lunar surface in 2029 as part of an international project.

.jpg )

According to Toyota, the three-year programme is slated to start from the fiscal year of 2019, and will be led by Toyota’s newly formed Lunar Exploration Mobility Works department.

The first year of the programme will be focused on identifying the challenges for driving on the moon’s surface and drawing up the specifications for the prototype rover.

Interestingly, Toyota mentions the prototype rover will be “a modified version of a standard production vehicle”. We wonder if a Toyota LandCruiser 200 would be a good starting point?

In the second year Toyota plans to design and manufacture a working prototype, with the third year earmarked for the prototype’s testing and evaluation.

Toyota hopes its rover design will be ready for deployment in 2029 and will be capable of exploring the moon’s polar regions, with expectations that it will be able to utilise the moon’s resources, such as frozen water, to keep it running.

Returning to the moon is a daunting task, but getting a manned lunar vehicle, much less one that would allow scientists and astronauts to work without their space suits, is an entirely different story.

For comparison, NASA’s Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), which was nothing more than two beach chairs strapped to a ladder-frame chassis, costed the agency USD$38 million to build.

Granted, the LRV was designed and built in less than two years and featured a battery electric drivetrain that could operate in temperatures of -128°C to more than 98°C. Plus, it was able to traverse the harsh lunar terrain peppered with craters and filled with cement-like moon dust.

To top it off, the LRV weighed in at a scant 208kg and could fold into a 1.5m-long and 0.5m-wide package in order to be stowed aboard the Lunar Module.

Likewise, Toyota’s proposed hydrogen-powered lunar rover would face similar technical hurdles such as electronics-destroying static discharge and the ever-pervasive moon dust.

Even though the company is one of the leaders in hydrogen-fuel-cell cars, developing a fuel-cell drivetrain for lunar operations 400,000km away from the nearest Toyota service centre will be uncharted territory for the Japanese car maker.

Adding to that, with weight being one of the primary hurdles of launching an object into space, getting a pressurised lunar rover with vital life-support systems to the moon would be a monumental challenge in itself.

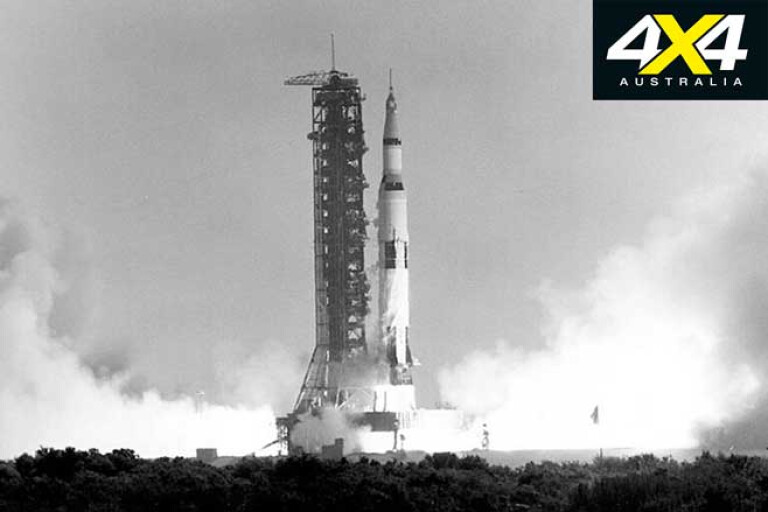

For every kilo of payload a rocket would have to carry, it would need to carry additional fuel which in turn adds more weight to the rocket. This exponential energy-to-mass requirement is how the Apollo space programme ended up riding on the world’s tallest and most powerful rocket ever built.

For now it is too early to tell if Toyota’s Lunar Exploration Mobility Works department will be able to find a realistic solution to JAXA’s goals of sending a lunar vehicle to the moon by 2029, much less build one that would be ready to land on the moon.

COMMENTS