WHERE a future of driverless cars once seemed some far-off dystopian nightmare, today that future is bearing down on us like a two-tonne SUV with no-one at the wheel.

Pilot trials are already taking place, and in 2017 Volvo will hand 100 autonomous cars to members of the public as part of its DriveMe project. Terrifying, no?

These Volvos will initially self-drive in ‘simple’ scenarios – one-way traffic, no pedestrians, central guardrail – before handing back to the driver when necessary.

Eventually, the machines will be intelligent enough to tackle complex urban driving.

The answer lies next door to Volvo’s Hallered proving ground in Sweden. Called AstaZero, the all-new facility opened in August 2014 and is dedicated purely to the testing and development of active safety systems.

Asta is an acronym formed from Active Safety Testing Area, and Zero alludes to the Swedish government’s target for road deaths and serious injuries.

“Our focus is now more on collision avoidance than passive safety,” says Jan Ivarsson, Volvo’s deputy director of safety systems. “We can make bigger gains with active safety systems.”

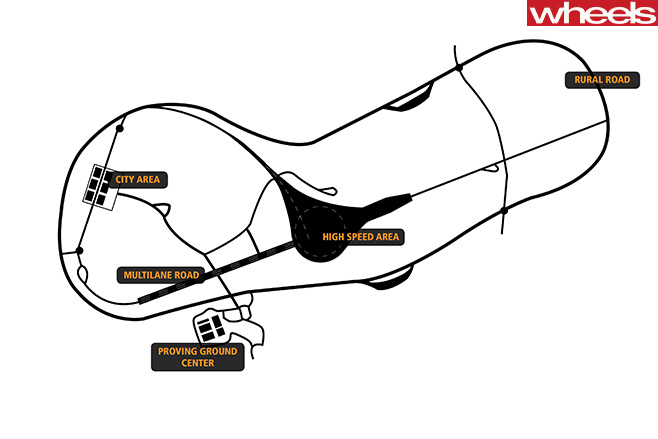

The 280 hectare facility is divided into different areas to replicate typical driving environments, and can accommodate up to 100 test cars simultaneously.

But anyone can schedule test time at AstaZero. It’s no trackday, but here’s what to expect.

The World’s Most Boring Road

Volvo is developing elk-avoidance technology here, hoping to reduce the 5 percent of Swedish accidents caused by the animals annually. As technology improves – faster-acting cameras with wider angles of vision – it might even stop us hitting a few ’roos.

The Ghost Town

Cars can be driven at each other (pictured top) –or at fake pedestrians or cyclists – with buildings blocking their line of sight, so the cars’ safety systems must detect hazards with very little warning, and respond quickly. While today’s systems can detect people and cyclists moving at relatively slow speed in front of the car, fake Harlem will help develop faster-acting systems that can manage more complex scenarios.

“We’ve seen a high level of reduction of in-car fatalities,” explains Ivarsson, “but you don’t get that with cyclists and pedestrians – in fact, there was an increase in Sweden last year. In young economies where you have cyclists and pedestrians and motorbikes, this is really the problem, so from a governmental perspective it will be an increasing focus.”

Numerous cars now offer lane-departure warning and lane-keeping assist features: electric power-steering systems combine with grille- or windscreen-mounted cameras to monitor lane markings, and vibrate the steering or actively turn it while you’re not paying attention. (“On average, drivers spend 20% of the time not looking at the road,’ reveals Ivarsson.)

When autonomous cars arrive, the need to accurately decipher road markings will become even more imperative. Think of the nightmare of making that work globally. Hence AstaZero has a multi-lane 700-metre straight road with road markings used throughout the world: solid lines, broken lines, Botts’ dots from the US, cat’s eyes from the UK… It’s like some inebriated road crew has gone on a rampage.

No, not a Hispanic sub-culture with Cadillacs on air suspension. “Low riders” are integral to the autonomous test process, and were specially developed at AstaZero. These car-sized remote-controlled platforms skim along the road surface on four tiny wheels at up to 100kph, with ‘top-hat’ foam structures used to replicate vehicle dimensions. It allows engineers or remote-controlled cars to simply drive at them. If a safety system designed to prevent an impact fails, the low-rider’s foam structure bites the dust, but there’s no damage to the test car. Low riders already exist at other test locations, but typically can’t exceed 80kph, and aren’t suited to poor weather conditions.

The High-Speed Area