The founding editor of Wheels, Athol Yeomans, has died at the age of 91.

Yeomans first suggested a new car magazine in 1950. He was 21 and working in the production department of K.G. Murray Publishing.

Fred Smith, Murray’s general manager, scoffed at the idea and, instead, started Man’s Life, Adventure Story and Master Detective. Predictably they soon disappeared, while Yeomans was fired for a practical joke on Smith that went spectacularly wrong. The motoring magazine didn’t happen.

Two years later, a freelancing (i.e. unemployed) Yeomans applied for a job at Hudson Publications. Only to be told by Norman Hudson that the advertised job had disappeared because he wanted to start a motoring magazine. Upon hearing this, Yeomans claimed “he almost passed out with desire” and persuaded Hudson that, with his editing experience on the short-lived monthly motoring journal Through The Windscreen, he should be employed on the new magazine. Hudson planned to call it Wheels.

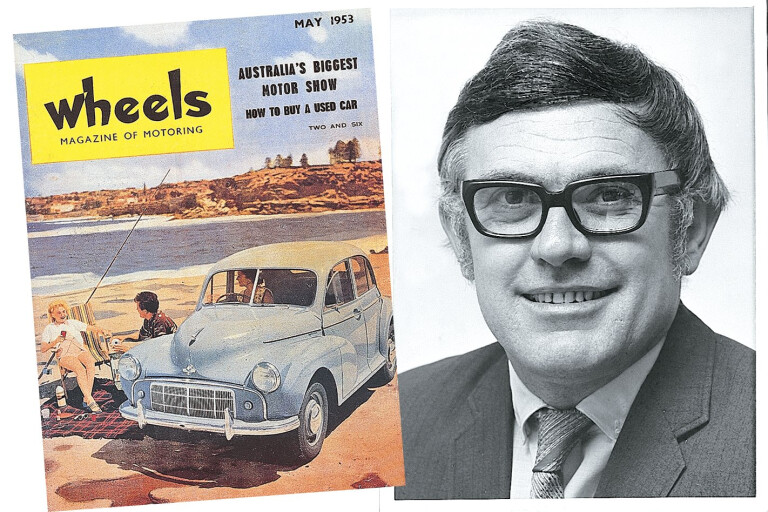

In September, 1952 Yeomans found himself “in a musty smelling stationery storeroom sitting at a table looking at a bare sheet of paper.” With photographer Barrie Loudon, the only other full-time staffer, Yeomans spent months planning the first issue, writing most of it himself. That first Wheels – May 1953, price two shillings and sixpence (25 cents) – was a sensation. Success was immediate - the 30,000 copies printed sold out in a couple of days. A few months later Wheels was selling 60,000 copies a month.

View the very first issue of Wheels Magazine

Athol Butler Yeomans, who has died at the age of 91, was initially employed as News and Feature editor, but went on to become Wheels’ first editor with the March 1954 issue and remained in charge until November 1956 when he resigned to travel.

Yeomans, well aware there was an opening for a decent car magazine, set out to create “a magazine which will make you want to read it.” Before Wheels there was only Motor Manual, a cheap scissors and paste operation, and the short-lived Cars, mostly reprints of American stories, plus Australian Motor Sports that only covered motor racing.

The creative Yeomans was determined that Wheels should be a different sort of magazine. For the 25th anniversary issue in 1978, he wrote, “I wanted to produce a magazine with some entertainment in it, which captured some of the adventure of motoring and motor sport. And I felt we should write about the dozens and dozens of characters in the game, whose exploits were never covered in other publications. I believed that enthusiasts would welcome a balanced coverage of news from all over, plus technical stories, travel and the rest.”

Wheels was printed in the basement of the Hudson office near Sydney’s Central Railway station - on newsprint quality paper, using the old letterpress process and with limited print shop capacity. Colour printing, like quality paper, was fearsomely expensive, so the only colour in Wheels was the cover.

Years later, without a raft of freelancers to help, Athol admitted that “writing an issue a month was beyond me.” The June issue ran late and, because it was so far behind the deadline, July became the August magazine. The July 1953 magazine remains the only time in 1648 issues (and counting) that Wheels didn’t publish.

Page 64 of the first issue carried small report announcing plans for the first Redex trial, a 6000-mile “reliability trial”. The timing was perfect for Wheels - no other publication attempted to cover the entire event, which instantly became front page news on a daily basis across the country. Stage by stage, Yeomans and other Hudson staffers, including Hudson himself, managed to follow the trial with Yeomans writing as they went. When the newspapers realised Wheels was on the scene, Yeomans and the others also wrote for the dailies. Wheels October 1953 was essentially devoted to the Redex.

Yeomans had a knack for finding talent: Peter Burden, the magazine’s first unofficial road test editor, went on to become the iconoclastic motoring writer for The Financial Review; Ian Fraser moved from Cars, to eventually become Wheels’ third editor, before a move to the UK where he first edited Car magazine and later became joint owner of the title. In an era when specialist motoring writers were rare, Yeomans developed a smart team of freelancers: Pedr Davis first wrote for Wheels in 1954; Charles Cruickshank took photographs; Charles Vaughan compiled the Wheels Garage page; Malcolm Hilbery, a young barrister, wrote a column The Law and You. Yeomans also found Gordon Wilkins, a former staffer on The Motor, who quickly became Wheels’ main man in Europe.

From the first issue Yeomans was keen to introduce reliable road testing, rather than just driving impressions. He wanted standardised specifications and genuine independent performance figures. Rather than just relying on the speedo reading to determine a car’s top speed, Yeomans and Burden timed the test cars, in both directions, over a set distance to determine their maximum speed. Famously, the first road test car – a 1954 Renault 750 – reached 58mph (94km/h), when the distributor claimed the 70mph (113km/h) as per the speedo needle. In the dramas that followed Yeomans eventually prevailed and road tests, and later comparisons, quickly became a staple of Wheels and remain so to this day. This objective road testing meant that within a few months, Wheels became Australia’s recognised motoring authority.

When Wheels was launched Holden, almost alone among the major manufacturers, employed a public relations department. Except the new magazine was ignored by Holden. During Yeomans three and a half years as editor, General Motors-Holdens refused to provide a car for road testing: the new FJ test car came from a dealer. The story appeared in the May 1954 issue, six months after the FJ launch.

According to Yeomans, Holden’s excuses included, “No cars”, “Not our image” and “Against company policy”. Athol was not impressed. In stark contrast, Buckle Motors (then NSW distributors of Armstrong Siddeley, Borgward, Lloyd Hartnett, De Soto and Citroen) happily provided demonstrator cars. The most sensational car of the time was VW’s original Beetle. Yeomans had to have one and predicted that rather than sell the estimated 40 to 50 a month in NSW “I told Bill Buckle he’d sell 10 times that number”. The air-cooled, beautifully-built VW, far tougher and more reliable than the British small cars, went on to become the second best-selling car in Australia behind the Holden.

Despite Wheels’ success, financial clouds hovered over Hudson Publications. Christmas eve 1954 was also pay day. Yeomans remembers Norman Hudson called the staff in and told them, “Well fellas, there’s no money in the tin. Come back in the New Year and we’ll square you up then.”

June 1955 was Hudson’s last Wheels, the following month ownership passed to K.G. Murray Publishing. General Manager Fred Smith again became Athol’s boss. At a welcoming dinner for the new staff Athol couldn’t help himself. He told the diners, “Not content with firing me once, Smith has contrived to pay $80,000 so he could fire me again.” Except he didn’t.

However, every word, every heading and every photograph that appeared in Wheels had to be approved by Smith, who now thought he knew everything about cars, and began suggesting embarrassing stories: “Never wash your car again” and “Lifetime batteries.” When editor Jeff Carter left Outdoors and Fishing to go freelance, Yeomans was also given responsibility for that title, plus Seacraft magazine. It was too much and Athol resigned after finishing the November, 1956 Wheels. It was time to travel overseas, though he continued to contribute to the magazine – his last motoring story on Citroen’s 1980s revival appeared in the July, 1986 magazine – and he wrote ‘In the Beginning’ for the 50th anniversary issue, May 2003.

After returning from Europe, which included a spell living in Spain, Yeomans spent most of his career writing and managing print media – in his own business and working for others. There was also an unhappy year in the late 1960s as head of Ford Australia’s public relations department. In 1976 Athol became executive director of the Company Directors Association and co-founded the world’s first training course for company directors. He continued to find time to write the occasional piece for Wheels and to enrol in a BSc in Earth Science at Macquarie University, graduating in 1986.

My first contact with Yeomans came after Ford lent me an imported, soft-top Torino GT. I spent so much time sideways in the 6.4-litre V8 that I complained to a junior PR-operative about the lack of adhesion from the totally overwhelmed seven inch D70 rubber. I was eventually shown into the Big Boss’s office to discover an unhappy Yeomans. He insisted the car was on the wrong tyres and blamed the test car garage. By the time I became Wheels editor in early 1971, he’d forgotten the incident. We lunched on an irregular basis, but Athol always took a keen interest in ‘his’ magazine and its direction.

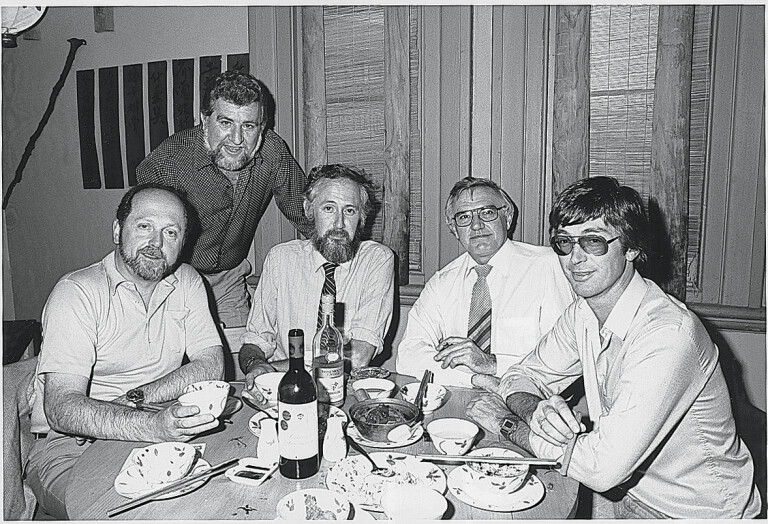

A decade later, having remarried, I discovered that my wife Erica and the Yeomans were close friends. The connection was cemented, even more so when Athol and Ayleen, his charming wife, with Ian Fraser (Wheels’ third editor), rented a wonderful house, built around a tiny chapel, overlooking Calino, a village in northern Italy. Learning that Erica and I planned to move to Italy in 1988 for me to work for Wheels and Autocar magazines, the Yeomans immediately suggested we stay at Santa Stefano while looking for a home. Through their landlady Contessa Camilla Maggi, whose husband was one of the founders of the Mille Miglia, we found a villa on the other side of Calino. It was our home for almost 10 years. Each year the Yeomans spent three months in Italy: we watched Grands Prix together on the TV, ate at Athol’s famous Australian Table at the magical Sensole restaurant on Mont Isola, the big island in Lake Iseo, and constantly talked cars and magazines.

Yeomans was immensely proud of his involvement with, and attachment to, Wheels and the progress that followed. Always curious, intensely intelligent and wonderfully generous, Athol Yeomans will be much missed by all who knew him.

COMMENTS