The Ford Ranger PX that went on sale in Australia in late 2011 and has just been superseded, is a pivotal product in Ford’s history.

Despite carrying over the Ranger name from its predecessor, it was a genuine top-to-bottom Ford product and not just a rebadged Mazda as was the earlier Ranger and all the Ford Courier utes before that. This was Ford responding to the growing global demand for utes by making the new Ranger an in-house engineering priority rather than just relying on someone else’s design.

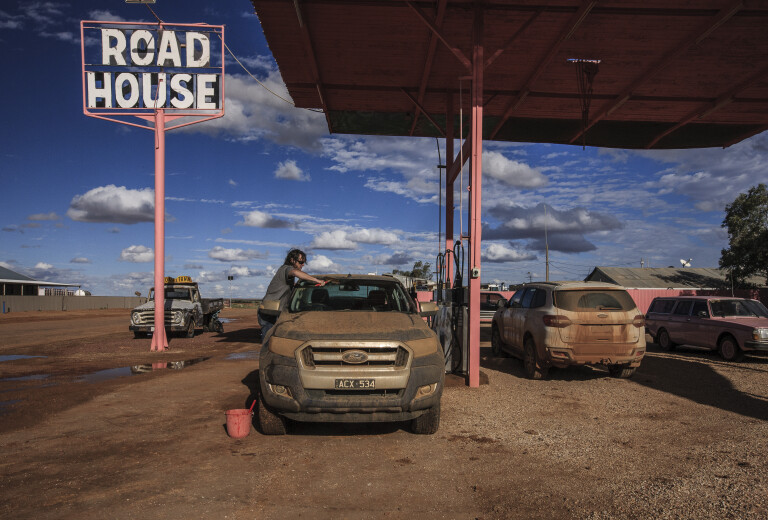

In what was a big-budget effort, Ford marshalled its considerable resources from all around the world to contribute to the design and then headquartered the development right here in Australia, which has subsequently proved to serve the Ranger well. This new Ranger was to be built on three continents and sold in no fewer than 180 countries, so it had to be ‘right’.

Upgrade your Ranger

Thankfully all the effort was worthwhile as the PX proved to be a standout design, not only on debut in late 2011 but also against the flood of newer rivals that have subsequently arrived, namely new-generation Holden Colorado, Isuzu D-MAX, Mitsubishi Triton, Nissan Navara and Toyota Hilux models.

Against its contemporaries the PX Ranger is notable for many things but none more important than its long-travel suspension and long wheelbase chassis. The long-travel suspension is just the ticket for bumpy back-roads touring in this country and it also underpins the Ranger’s off-road excellence.

For its part, the notably long wheelbase means class-leading combined front and rear legroom in what is a very spacious cabin without compromise to the length of the rear tub, always the crucial point with a dual-cab.

The PX’s 3.2-litre in-line five-cylinder turbo diesel, the biggest capacity engine to appear in the class, also sets it apart from its rivals, which are almost exclusively powered by smaller capacity four-cylinder turbo diesels. Even the V6 diesels in Amarok and Mercedes X-Class are smaller in capacity.

During its time the PX received two major upgrades, the first in 2015 (PX MkII) and then in 2018 (PX MkIII), and aside from the 3.2 five-cylinder was also available with a 2.2-litre four-cylinder turbo diesel and, from 2018, a 2.0-litre four-cylinder bi-turbo diesel mated to a 10-speed automatic. A petrol engine (2.5-litre four) was only offered in 4x2 models.

Given the five basic powertrain options in 4x4 models and the fact the MkII and MkIII upgrades involved significant engineering and not just tech add-ons and styling changes, it’s no surprise that not all 2011 to 2022 Rangers are created equal. Buyer beware!

Ford Ranger history

When released in October 2011, the Ranger came in 17 4x4 variants, two single cabs, three extended cabs and five dual cabs, with XL, XLT and Wildtrak equipment levels. Four models, the two single cabs and one each of the extended cabs and the dual cabs were commercially oriented cab/chassis models. Prices ranged from $38K to $57K plus on-roads.

The entry level 2.2-litre four-cylinder turbo diesel (a Ford ‘Puma’ design dating back to 2004 and also seen in Land Rover Defenders from 2011-16) claimed maximum power and torque figures of 110kW and 375Nm, and was offered with both a six-speed manual and a ZF six-speed automatic.

The optional 3.2-litre in-line five-cylinder diesel, also a Ford design that had debuted in the Transit van in Europe five years earlier, claimed a far beefier 147kW and 470Nm. Despite the significant difference in performance, especially useful for heavy towing or load carrying, the 3.2 only asked a $2500 price premium over the 2.2, which probably explains its runaway sales popularity over the 2.2 even if the 2.2 found favour with fleet buyers.

Like the 2.2, the 3.2 was also offered with either a six-speed manual or a ZF six-speed automatic, and with both engines the auto attracted a $2K price premium.

Standard equipment ran to what was then cutting-edge safety technology that included electronic stability control, electronic traction control, trailer-sway control and roll-over mitigation. Front, side and curtain airbags were also part of the impressive safety package.

Most significantly for off-road use, four-wheel electronic traction control proved a game changer and was enormously more effective than a rear limited-slip, which was the standard traction aid up until that time.

A driver-switched rear locker, standard on XLT and Wildtrak and optional on most other 4x4 models, also added to the Ranger’s off-road weaponry and started the rear locker ‘trend’ in the ute sector.

The PX Ranger 4x4 also offered a 3350kg maximum towing capacity, a class-leading figure at the time, which was the first blow struck in the “towing capacity wars”. The Ranger’s maximum towing capacity was subsequently lifted to 3500kg.

In 2015 the PX Mk II arrived with bolder front-end styling, a redesigned interior and various equipment upgrades, but the most significant changes were under the skin and started with pleasingly calibrated electric power steering that brought effortless wheel-twirling at parking and off-road speeds yet still offered excellent feel and feedback at highway speeds. Suspension revisions also helped improve the Ranger’s already impressive dynamics.

The 3.2 also gained a new turbo and revised fuel injection that fattened up the torque and power curves, even if the maximum figures remained the same. On the road the difference in response was obvious, as was the fact the 3.2 was now quieter and more refined than before, a welcome change.

Also welcome was the much better shift quality with the 3.2’s manual thanks to a change from a linkage to cable selector. The 2.2’s power and torque figures were also bumped to 118kW and 385Nm.

The MkII’s off-road performance was also significantly improved via a simple tweak of the powertrain and chassis electronics, where the activation of the driver-switched rear diff lock no longer cancelled the electronic traction control on the front wheels, as was the case previously. In practice it made a significant difference in tough off-road going where you’re scrambling for every bit of traction. The driver-switched rear locker was standard on all 4x4 dual cabs by that time.

The XLT with its larger touchscreen, Ford’s SYNC 2 connectivity, embedded sat-nav, tyre-pressure monitoring, a 12-volt outlet in the tub and standard 3500kg factory towbar was unsurprisingly the volume-selling model. Radar cruise control, forward-collision warning and lane-departure warning made up the optional ‘technology pack’ for XLT and Wildtrak.

In 2018 the PX Mk III arrived as the MY19 model and brought an all-new powertrain in the form of a 2.0-litre four-cylinder bi-turbo diesel that claimed 157kW and 500Nm, both stronger figures than the 60-per-cent-bigger-capacity 3.2 five, and backed by an automatic gearbox with no less than 10 speeds.

There was no manual with the bi-turbo and it was only available in XLT and Wildtrak models. Meanwhile the 2.2 and the 3.2, both still available with six-speed manual or automatic gearboxes, continued to be sold largely unchanged alongside the new powertrain.

The MkIII brought a second round of front-end styling revisions with the XLT and Wildtrak also getting LED daytime-running lamps and HID headlights.

In a sign of the times, automatic emergency braking was introduced on the Wildtrak as standard equipment and as an option on XLT. Radar cruise, lane-keeping assist and lane-departure warning and forward-collision warning also became standard on the Wildtrak but remained an option on XLT.

SYNC 3 connectivity with Apple CarPlay and Android Auto, previously introduced on XLT and Wildtrak, also became optional on XLS, while push-button start was introduced on XLT and Wildtrak. Significant suspension revisions for the MkIII across the range were claimed by Ford to offer better stability when towing yet more compliance for general and off-road driving. The impressively engineered bespoke-chassis Raptor capped off the MkIII update.

General driving

All Ranger models are good to drive and compare favourably with their immediate rivals in ride, handling and general road manners. MkII models with electric power steering and the revised suspension are a notable step up from the original offerings, while the MKIII suspension changes didn’t seem to really improve things notably, despite Ford’s claims.

The often-overlooked 2.2 performs better than you may think, and for general driving is fuss free and more frugal than the 3.2. The 2.2 probably mates best with the six-speed manual and the good news is the shift quality was good right from the start, unlike the 3.2 manual’s problem not fixed until the MkII update. The 2.2 also has sufficient power to work well enough with the automatic, if that’s your preference. The 2.2 is, however, only available in the lower-spec models.

Moving up to the 3.2, it’s a notably better engine in the MkII than it was in the original model, thanks to its improved response and refinement. For manual 3.2 buyers the improvement with the MkII is even more notable due to the much-improved shift quality.

Compared to the improved 3.2, the 2.0-litre bi-turbo is both more responsive and more frugal, with its 10-speed automatic no doubt playing a role in both these achievements. The bi-turbo is also quieter and generally more refined than the 3.2, although the 3.2 has a more pleasing and relaxed manner compared to the more frenetic and revvy nature of the bi-turbo. The bi-turbo’s 10-speed auto isn’t perfect either, with an occasional hesitant and clunky shift, which detracts from its otherwise excellent refinement.

Off-road driving

The PX Ranger’s long-travel suspension is the secret to its considerable off-road prowess and makes it better off road than most of its contemporary rivals. In fact, it’s well ahead of Triton, Navara, D-MAX and the pre-2016 update Colorado. In its MkII iteration where the electronic traction control on the front wheels stays active even when the rear locker is engaged, the off-road ability is as good as it gets in terms of mainstream utes.

The best off-road models are MkII or MkIII 3.2s, with either the manual or automatic gearbox. The automatic is probably the best bet off road for ease of driving – especially for soft sand or steep hills – but some people just prefer a manual.

The bi-turbo isn’t quite as happy off road due to a less-than-slick performance from the 10-speed automatic in low range where it can struggle to get its shifts right even with ‘manual’ selection. It still does the job, but it’s not always happy.

Towing

If your requirement is for a heavy-duty tow vehicle then the 3.2, especially in the MkII or MKIII iterations, is again the best bet. Manual or automatic is again a personal preference, but towing with an automatic is just easier on the driveline and the auto’s manual-style override shift still gives you manual control in more demanding driving conditions, up or down steep hills.

Surprisingly the 2.2 has the same tow rating as the 3.2 (originally 3350kg and then 3500kg) but is probably best at towing more moderate loads up to something around 2500kg.

On paper the bi-turbo with its 157kW and 500Nm should be the best tow vehicle, but our heavy-duty tow testing has shown that the engine nor the gearbox likes very heavy tow loads in demanding conditions. In fact, many rival utes with lower power and torque figures outperformed it in our last tow test and it’s certainly well short of the 3.2 under more extreme conditions and probably best at light and moderate towing duties.

Reliability and service

In all its iterations the Ranger has proved to be generally problem-free and reliable, although it’s also fair to say the bi-turbo and 10-speed powertrain hasn’t been as reliable as the others. Perhaps that’s because both the 2.2 and the 3.2 and their respective gearboxes have been in service for five or more years when they debuted in the Ranger in 2011, whereas the bi-turbo and 10-speed was a brand-new design when it appeared in the PX MkIII and Raptor.

Not that the 3.2 has proved 100 per cent perfect. The fourth cylinder ran hotter and under extreme duress, would burn the top off the injector and potentially burn a hole in the piston. Exhaust gas regulators can also split on 3.2s and 2.2s, causing additional problems if not attended to. Like all high-pressure common-rail diesels, the 3.2 and the 2.0 react poorly to contaminants and water in fuel. The dual-mass flywheel on manual 3.2s was also prone to failure under heavy towing loads.

All the minor glitches of the original PX – like the standalone Bluetooth module – were addressed with the MkII. MkII owners who complained about the annoying door-open warning chime were also treated to a free software fix.

Service-wise there’s also a potential problem when doing oil changes on the 3.2. While it might seem right, if you let the oil drain for too long the pump bleeds out and won’t self-prime after the oil is replenished. That means no oil pumping through the engine on restart, which is a recipe for catastrophic engine failure. For DIY on 2.2 and 3.2 models, it’s worth noting that many Mazda BT-50 parts are cheaper than identical Ford-boxed parts.

In its still relatively young life the bi-turbo and 10-speed powertrain has suffered injector problems from early on with Ford doing two field-service campaigns to fix the same, while the gearbox problems (other than a clunky shift) have been serious enough to be the subject of a widespread safety recall.

Seems also that the bi-turbo needs timely oil changes, and if you ignore the service reminders the engine can go in to a reduced power mode even if the dipstick says there’s plenty of oil. We also know of a recent case of a 126,000km bi-turbo engine with a blown head gasket where Ford didn’t just replace the gasket but replaced the engine. Read in to that what you may.

If you’re buying a second-hand bi-turbo you do, of course, have the reassurance of the five-year/unlimited km warranty that was part of the MkIII MY19 upgrade.

In all there have been 13 safety recalls across PX, PX MkII and PX MkIII models, and when buying second-hand you can’t take it for granted that the previous owner(s) actually had the work done.

And on a closing note, the electric power-steering may be nicer to drive but the old-school hydraulic power steering of the original PX is potentially more robust and gremlin free for rough and tough bush work.

Market snapshot

Given the long-term new-car sales success of the Ranger, there’s no shortage of second-hand examples for sale. Try around 5000 second-hand 4x4 Rangers for sale nationwide on just one used-car sales website alone, admittedly the biggest of many in Australia.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that second-hand prices are strong and demand is probably even stronger. The cheapest 4x4 Ranger on the sales site in question was asking $15,500. And it was a single-cab with 350,000+ kilometres on the odo, although it did have the 3.2 (manual ’box). The 3.2 (usually paired with the six-speed auto) is the most common engine available second-hand, although the 2.2-litre four (manual or automatic) is surprisingly common, while the later bi-turbo and 10-speed powertrain is surprisingly uncommon.

Moving up from that $15.5K single cab, the cheapest extended cab (a 2014 3.2L manual with nearly 400,000km on it) was $17K, while the cheapest dual cab (a 2014 2.2L auto) was asking $18K. The cheapest dual cab with the 3.2L (auto) was at $18.5K and that was for a cab-chassis and not a factory tub pickup.

Moving up to the PX MkII and prices start at $26K for a 2016 single cab or 2015 dual cab, both 3.2L autos. PX MkIII dual-cab prices started at $35K for a 2019 3.2 auto. Meanwhile, bi-turbo prices started at $45K for a 2018 extended cab, with the cheapest bi-turbo dual cab a 126,000km 2018 model for $46K.

Note that models listed as 2015 can be either a PX or a PX MkII, while 2018 models can be either a MkII or a MkIII.

Ranger Raptor

The Raptor, which appeared at the same time as the PX MkII upgrade, deserves and needs its own place in any discussion about buying a second-hand Ranger. It is a completely different beast – in the nicest of ways – to every other Ranger model.

Essentially it has a very different rolling chassis to bread-and-butter Rangers and that transforms the way it performs both on and off road. And brilliantly, the changes are that clever that the Raptor is both better off and on road. Aside from a reduced towing and load capacity (but still 2500kg and 750kg respectively) there’s no compromise here.

The Raptor is not just a Ranger with a lift kit and off-road wheel and tyre package. The Raptor’s chassis has been significantly altered with 150mm wider front and rear tracks via different front A-arms and a different rear axle housing, 46mm more ground clearance, 30 per cent more suspension travel at both ends, bespoke Fox-brand dampers (the rears have ‘piggyback’ reservoirs) and a sophisticated coil springs-Watt’s link rear suspension. No cheap and nasty Panhard rod here! The package is finished off with four-wheel disc brakes and 285/70R17 BFGoodrich All Terrains.

If the Raptor was open to criticism, it was that it used a standard 2.0-litre bi-turbo diesel, 10-speed powertrain and part-time 4x4 system, where the brilliant chassis was screaming out for a stonking big petrol V8 and full-time 4x4. Given that the new model Raptor answers both the call to more power (no V8 but a sizzling 292kW twin-turbo petrol V6) and full-time 4x4, this may have a notable impact on the second-hand value of first-generation Raptors.

Mazda BT-50: Twin under the skin

The Mazda BT-50 released just weeks after the PX Ranger in late 2011 was essentially the same ute save for a few details. The front and rear styling was obviously different, as was the cabin presentation and equipment details, but mechanical changes ran no deeper than a faster steering-rack ratio and slightly firmer suspension dampers.

The notable difference between the BT-50 and the Ranger moving forward, was that Mazda didn’t adopt the PX MkII and MKIII changes so that the BT-50 remained essentially the same throughout its life except for styling and equipment upgrades. Last year the Ranger-based BT-50 made way for a new model, essentially a reskin of the new-generation Isuzu D-MAX that arrived here in late 2020.

The lesson here is that if you’re interested in a PX Ranger you should also look at BT-50s; although, the BT-50 never sold anywhere near the volume of the Ranger, so it’s far rarer second hand.

COMMENTS