Here we go. I can hear Editor Matt’s rumbling guffaws falling out of that beard. ‘Roothy’s doing tech again!’ Hey, I’m pretty good with a hammer and chisel, so that gives me the right to have a go at any rate.

Last month we had a look into diesel fuel pumps because that’s what I was getting done for the new motor in Milo 2. But that’s a 12HT, so it’s a turbo-diesel motor from the factory. And turbos, as any fan of oil burners will tell you, make diesels go really hard.

But they’re not exactly great lumps of cast iron nailed together with said hammer. Actually, the first ones were... almost. Swiss engineer, Alfred Buchi, patented the concept of using exhaust-gas pressure to drive a fan that pumped air into the intake, which meant heaps more power back in 1905. It was another 20 years before they started tacking turbos onto diesel engines, but metallurgy and lubrication hadn’t advanced enough to cope with the speeds and pressures required in smaller engines so the technology was mostly used in big ships and a few stationary motors, which used low-revving, big-capacity diesels.

WWII saw the development of the gas turbine, which brought a whole new world of possibilities to building efficient turbochargers. That’s because, at its simplest, a turbocharger is a couple of gas turbines on the same shaft. One end gets spun by the exhaust gases shooting out the manifold, which in turn spins a fan at the other end, forcing air into the intake at a higher velocity. Done right there’s an increase in power and fuel economy because compressing the air squeezes more oomph out of the fuel. There, how’s that for a technical explanation?

Naturally aspirated diesels nearly always produce a lot less power for the same capacity as a petrol engine, and they’re heavier thanks to the need to use components strong enough to handle double the compression. That gives the old diesels a power-to-weight disadvantage straight away, as anyone who has tried punting an old 1HZ Toyota or 4.2 Nissan up a hill will tell you – although that’s if they even get a chance to talk between manic downshifting.

So add a turbo (generally a relatively light bit of kit) and you punch that power back into the diesel. In fact, when you need power – like climbing that hill with a trailer or caravan on the back – the first thing you do is open up the throttle which pumps more fuel into the motor, making it work harder which forces even more exhaust gases through the turbo.

Dirty Work: What's Milo's future?

It spins harder, you get more air, more power and more torque, and that’s why almost every manufacturer these days fits a turbocharger as standard to their diesels. Technology has advanced so far in lubrication, metallurgy, bearings and mass manufacturing that if you ain’t got a ‘hair dryer’ hanging off your modern oil burner it’s because it fell off.

Diesels and turbos go together like cheese and crackers. But when you start looking at the heat generated by slowing down exhaust gases and the revolutions these fans spin at – more than 80,000rpm isn’t out of the question – you can see how things can crack and turn to cheese pretty quickly if you get it wrong.

The turbocharger on Milo 2’s 12HT is a pretty basic bit of kit, but it still does all that and more and has done so for at least the 450,000km on the odometer. There are no signs of it having been apart, and it’s leaking a little oil which indicates it needs a freshen-up at least. So off I go to MTQ again to see what the go is. After a yarn with Mitch I was lucky enough to get the ‘special treatment’ again and got to go through to the air-locked, super-clean room where resident turbocharging expert Mark works his magic.

My wife had a totally different version of ‘special treatment’ reserved for me when Normie pulled up his tilt tray and dropped me and the truck off rather late that night. I’d been so excited by what I saw I had to drop by the Mudflats Hotel and let the lads know, too. And it was darts night and I might have stayed out just that bit too late.

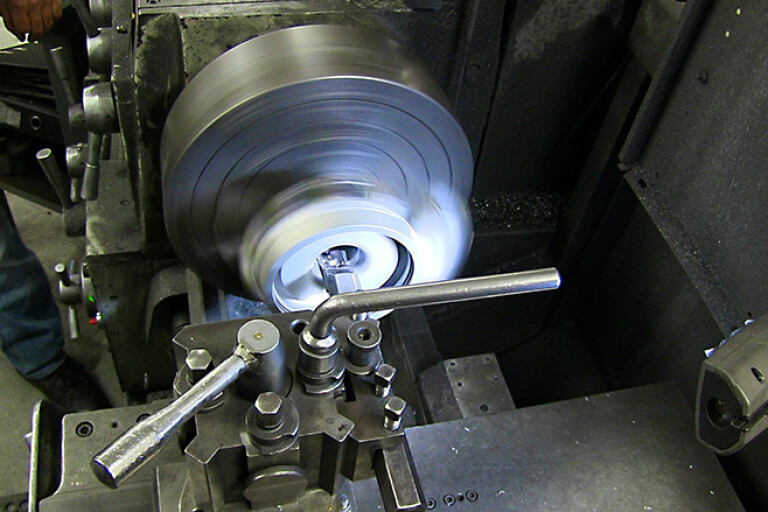

For a mug bush mechanic like me it’s truly extraordinary to see someone use a lathe with the degree of precision Mark exhibited. What he did was lathe out the chamber in the aluminium air-side of the turbo to accept a slightly bigger fan. It’s a known diesel hot-up trick that’s nicknamed ‘flowing’ because by pumping more air for the same sort of exhaust effort the whole process accelerates power and torque production exponentially again. More air makes more power, which in turn makes more air and more power – and so on and on.

Dirty Work: A new Hilux, an old Landie or a 40 Series?

This was achieved by using the new fan as a guide for what was essentially a hand-tooling job on the lathe. Mark’s done this a heap of times for many years so he’s probably got some natural starting profile anyway, but from then on it’s a slow and precise process with constant stops to check that the new chamber mates to the fan. Clearances are measured in hundredths of thousands of an inch, or whatever the ‘metric’ version of that happens to be.

That’s only part of the operation, though. The shaft has to be measured and checked for wear, the bearings replaced, and the whole plot put back together so it’ll make more power for even longer this time around.

Shaft wear is critical for obvious reasons, seeing as turbos usually spin about 20 times quicker than the motor. So 3000rpm on the tacho could mean 60,000rpm or much more on this shaft.

Shaft wear is critical for obvious reasons, seeing as turbos usually spin about 20 times quicker than the motor. So 3000rpm on the tacho could mean 60,000rpm or much more on this shaft.

For a motor-head like me this kind of stuff is fascinating. It keeps teaching that same old lesson preached loudly last month, though, doesn’t it? With components like this performing in super-hot, super-fast environments, suddenly lubrication and cooling (which are closely related) is everything. Yep, it’s all down to quality oils and lots of regular changes with good filters fitted at the same time.

Roothy visits Front Runner, South Africa

If anything, that’s more critical for the modern diesels that make so much torque from such comparatively small-capacity motors. The brochure in the D-Max I was testing last week indicated 440Nm from its 3.0-litre motor, and it isn’t even the biggest donk in the dual-cab class. The Chev V8 in my old Jag has twice the cubic inches and makes maybe 380Nm on a good day. There’s a whole lot of stomping going on in those turbo-diesels, and heaps of revving, too.

My advice for the long haul? Learn to change your own oils and filters. It’s not hard and you’ll only make a big black mess of it for the first decade or so, unless you’re me, and then it’ll be a lifetime of spills and splashes. Worth it, though. You can choose your own quality oil rather than letting the mechanic’s accountant make that decision. The same goes with the filter, too. And with the money saved on labour you can afford to do it as frequently as required, and you can afford to bung in a fresh filter every time and still have something left over for a cleansing ale.

Hang on. That’s when the trouble started. I think I’ll stop right here.

COMMENTS