“If I’d been in Bomber Command in 1943, I’d have bombed the Nürburgring every single night until it was gone.” It’s fair to say that James May hates the Nürburgring. He hates it for what he thinks it has done to the ride quality of modern cars and the effect it has on his chronic lumbago.

He’s also quite wrong.

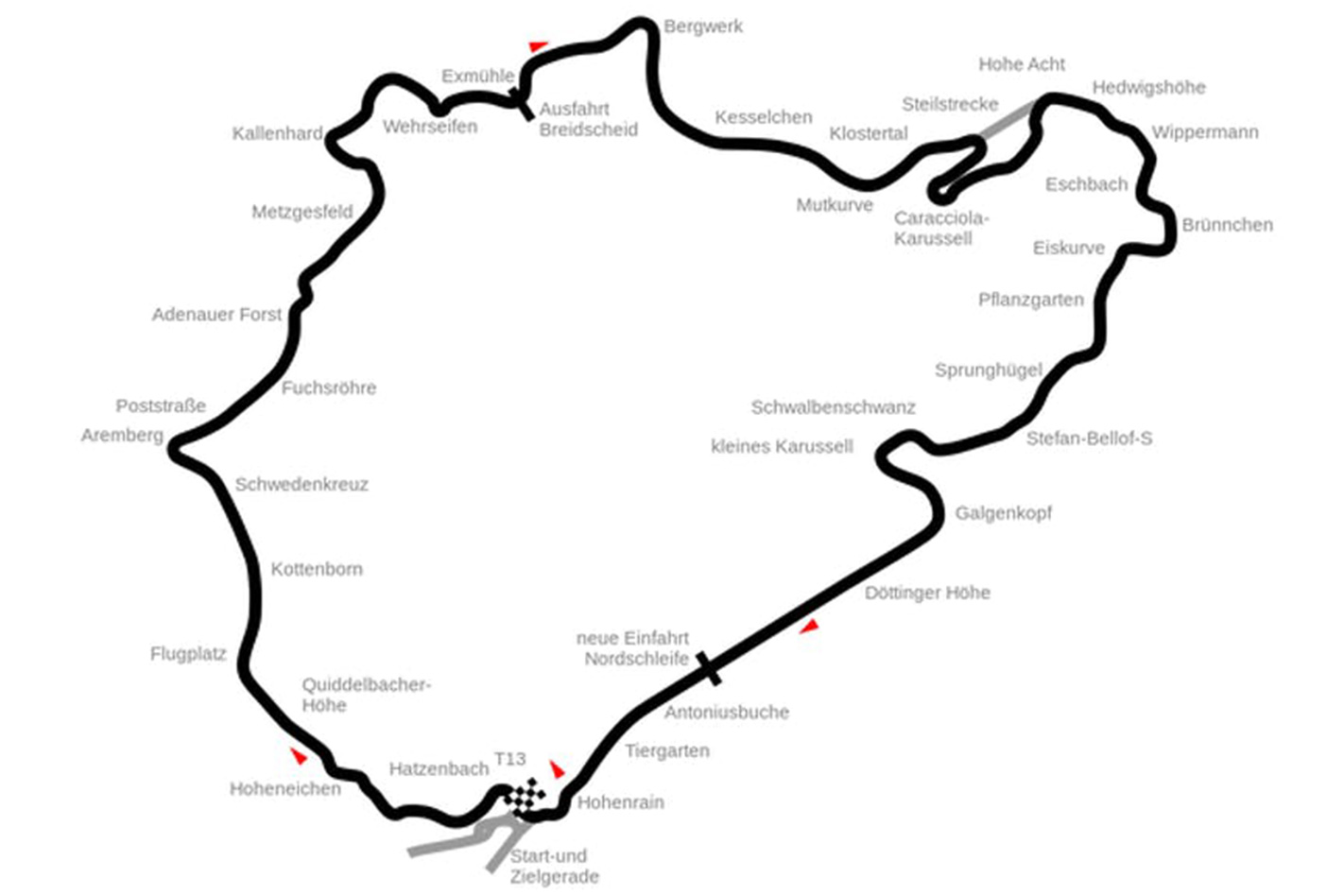

The reason why should be self evident. The Nürburgring is a road, with all the accompanying cambers, crowns, variable surfaces and bumps. Anyone who has driven around it will be instantly aware that it’s about as far from a homogenous graywacke-surfaced Tilkedrome as your local pockmarked high-street is. It also includes, almost by chance, virtually every combination of gradient, corner radius and surface condition manufacturers could hope for, which makes its 20.832km lap an almost perfect laboratory for accelerated road testing. Saying that a car fettled at the Nürburgring makes for a bad road car is akin to saying that cars tested on the road make bad road cars. It’s clearly a nonsense.

Cars developed to eke very millisecond out of a Nürburgring lap are another thing altogether. Anything optimised for a lap record and then sold to the general public is likely to ride with all the suppleness of a trolley jack and it’s these cars that Captain Slow ought to be directing his ire towards.

Such is the regard that the Nürburgring is held in that many manufacturers will program their chassis rigs with a virtual lap. I’ve seen a Mercedes-AMG at Affalterbach being pounded around a digital representation of the track. It’s quite amazing to see the front end dive as the car ‘brakes’ into Breidscheid, then squat at the rear under full acceleration before feathering the gas into Ex-Mühle and then ramping steeply up towards Laudalinks. The engineers there have never found anything better for durability testing.

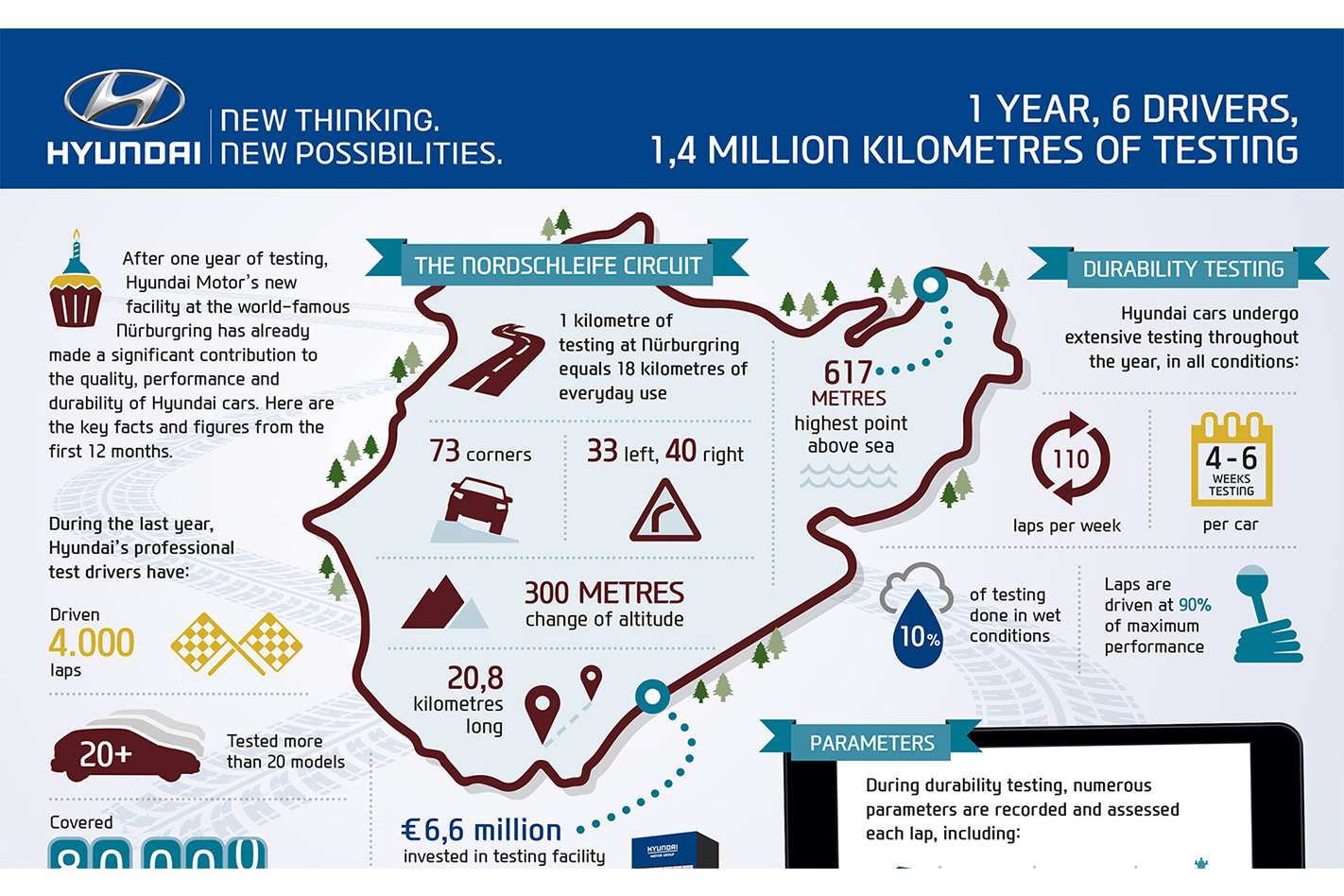

When Hyundai opened a vast four-storey test centre at the Ring, it didn’t do so to chase records. Some six years after it opened, Hyundai has yet to publish a single laptime. It understands that there are other benefits. Allan Rushforth, then Senior Vice President and COO of Hyundai Motor Europe, commented: “Quality is one of Hyundai’s core values and it is key to achieving customer satisfaction. The Nürburgring is the ultimate location to test vehicle durability, and we’re able to apply what we learn there to all of our vehicle development projects.” Note the word durability. Not ultimate speed, durability. Making products that stand up in the real world, for real buyers like us. Want the wheel bearings in your Tucson to last for 200,000+ kilometres? Thank Nürburgring testing.

Sometimes the results aren’t pretty. Koenigsegg crashed a One:1 in 2016 after it experienced an ABS fault in the high speed Foxhole section. In a statement, the company said: “Our engineers spent several hours on Wednesday, July 20th, replicating the fault using a similar car at our factory test track. The left front wheel ABS sensor was disconnected and ABS-level braking force was applied. We found results that were entirely consistent with those experienced by the One:1 at the Nürburgring.”

In other words, the Ring exposed a safety issue that might otherwise have sneaked through to production.

Finally, it’s worth asking yourself exactly how relevant the much-vaunted laptimes are in any case. The level of preparation that goes into major manufacturer record runs is just berserk. Sticky tyres that you’d trash in one session on a circuit, gun drivers who spend days driving back and forth,learning each corner to millimetric precision, a cage in the car that stiffens its chassis (under the guise of driver protection) and a whole host of other factors combine to deliver a result for the marketing department that you could never hope to replicate.

So while the Nürburgring can be a valuable force for good in the development of durable, safe road cars, it can also be a corrupting influence. While not all TV hosts appreciate the difference, fortunately most car manufacturers do.