The other day I had the opportunity to drive a bog-standard GQ Patrol.

This was first published in 4X4 Australia's September 2015 issue.

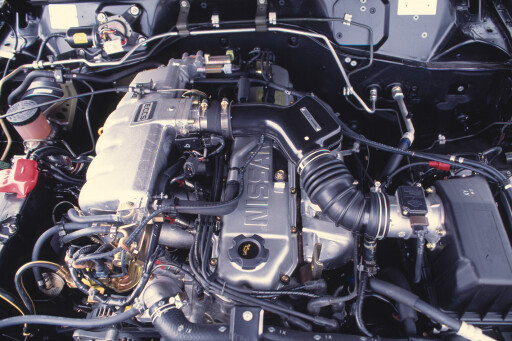

It was a mid-spec wagon, built in December 1990, and powered by the legendary TD42 4.2-litre naturally aspirated, indirect-injection, six-cylinder diesel donk. And it was a real eye-opener!

Other than worn shocks, saggy rear springs and a few minor dings in the body, this Patrol was in remarkably good shape for a 25-year-old vehicle with 338,000km showing on the odo.

As I walked around its perimeter, I was astounded that a vehicle I once considered to be somewhat of a behemoth looked so small by today’s standards. Park a standard GQ Patrol next to a current-generation Ford Ranger and the old girl looks positively tiny.

As I walked around its perimeter, I was astounded that a vehicle I once considered to be somewhat of a behemoth looked so small by today’s standards. Park a standard GQ Patrol next to a current-generation Ford Ranger and the old girl looks positively tiny.

When I plonked my rear into the driver’s seat, the square-edge 1980s-styling was an affront to my senses (as was the lack of a cup holder for my soy latte) but all of the controls were in familiar places and it didn’t take long before I felt right at home seated in the GQ.

The view through the upright windscreen and across the flat bonnet was much better than I remembered, and the low waistline and deep windows ensured great visibility to the sides, certainly much better than many of today’s curvy, stylised 4x4 wagons.

I fired up the big oil-burning six and set the hand throttle out a few millimetres to help it settle into a nice idle. Imagine that! No electronic injection to look after fuelling, but a plastic knob the vehicle operator has to set. After letting it warm up for a couple of minutes, I slipped it into gear and was away.

I fired up the big oil-burning six and set the hand throttle out a few millimetres to help it settle into a nice idle. Imagine that! No electronic injection to look after fuelling, but a plastic knob the vehicle operator has to set. After letting it warm up for a couple of minutes, I slipped it into gear and was away.

First gear proved remarkably short and I soon remembered that second-gear starts were the order of the day, unless of course on an incline. And you have to be slow and deliberate with the gear lever if you want to avoid any graunching when shifting.

I was soon on the freeway, heading west out of town and, while anything but powerful, the Patrol certainly had enough on tap to cruise comfortably at 110km/h. But then I got caught behind some slower-moving traffic in the centre lane and, as I pulled out into the right lane to overtake, I put my foot down on the go-pedal and waited patiently for the response.

‘Lethargic’ was the word that first came to mind. And I recalled using this word many times in the many vehicle tests I had written in the 1990s as a queue developed behind me. When new, the TD42 GQ Patrol made a claimed 85kW at 4000rpm and 264Nm at 2000rpm.

‘Lethargic’ was the word that first came to mind. And I recalled using this word many times in the many vehicle tests I had written in the 1990s as a queue developed behind me. When new, the TD42 GQ Patrol made a claimed 85kW at 4000rpm and 264Nm at 2000rpm.

So even if this quarter-of-a-century old GQ Patrol was mustering those power and torque figures, it wouldn’t help the cause much when trying to accelerate quickly from 90km/h back up to 110km/h. It’s little wonder that engine conversions and aftermarket turbo and intercooler kits were so popular back in the day, and why all modern diesel engines are now turbocharged and intercooled.

As I continued on my way and the surface changed from freeway to bumpy secondary roads, another term that I hadn’t used since the ’90s came to mind: ‘scuttle shake’.

This term refers to body vibrations, or shudders, as a vehicle drives over bumpy surfaces, and was coined to describe the phenomenon exhibited by convertibles due to a lack of lower structural rigidity. It could also be applied to four-wheel drives, including the GQ Patrol, that had significant chassis flex.

This term refers to body vibrations, or shudders, as a vehicle drives over bumpy surfaces, and was coined to describe the phenomenon exhibited by convertibles due to a lack of lower structural rigidity. It could also be applied to four-wheel drives, including the GQ Patrol, that had significant chassis flex.

Despite the lack of performance on the road, and the elevated NVH (noise, vibration and harshness) levels, the GQ Patrol was truly amazing once off the blacktop.

With loads of wheel travel from its coil-sprung live-axle suspension, decent low-range reduction and ample low-rpm torque, the GQ calmly idled over off-road obstacles that would have modern 4x4 wagons desperately calling on their arsenal of electronic traction aids and clever computer-controlled off-road programs. And bear in mind that this standard vehicle I was driving had pretty-worn highway tyres on it.

My recent GQ Patrol experience confirmed a theory I’ve had for some time; modern four-wheel drives have gone soft. Sure, they are very capable off-road thanks to their clever electronics, but their basic underpinnings are designed more for on-road ride and comfort than off-road capability.

My recent GQ Patrol experience confirmed a theory I’ve had for some time; modern four-wheel drives have gone soft. Sure, they are very capable off-road thanks to their clever electronics, but their basic underpinnings are designed more for on-road ride and comfort than off-road capability.

The next time I do the Madigan Line or the Gibson Desert, I’ll be taking a ‘traditional’ 4x4, one with live axles at both ends and loads of ground clearance, although I fear that vehicles like this are not long for this world.

COMMENTS