The conventional wisdom is that electric vehicles will upend the automotive establishment. Electric vehicles are cheaper to design and engineer than internal-combustion engine vehicles. They can be built using off-the-shelf components such as e-motors, inverters and battery packs readily sourced from third-party suppliers. And their simpler platforms potentially have a longer lifecycle, requiring only a new ‘top hat’ – bodywork and interior hardware – every few years to keep consumers interested, with functional improvements delivered via over-the-air software upgrades.

The conventional wisdom is that, unburdened by legacy technologies, legacy factories, legacy brands and legacy thinking, a new wave of lean and agile electric vehicle manufacturers is poised to finally break through the cost and complexity barriers that have long insulated conventional carmakers from outside competition. Want proof? Just look at Tesla, say the pundits. A Silicon Valley start-up that built its first electric vehicle in 2009, Tesla finished 2020 valued at more than industry behemoths Volkswagen, Toyota, Mercedes-Benz and General Motors – combined.

But the conventional wisdom is wrong, says Volvo’s chief technology officer, the aptly named Henrik Green.

Green acknowledges the technology arms race unleashed by the new electric vehicle manufacturers, and the entrance of tech companies into the sector, challenges the car industry’s traditional ways of working. But he says that doesn’t mean the electric vehicle newcomers have an inherent advantage over the old order.

The popular idea that electric vehicle powertrains mean simpler vehicle architectures that can underpin more types of vehicles and can be kept in production for longer is flawed, says Green. “It’s easy to fall into the trap that electric vehicle platforms will be simpler and have longer model cycles,” he says. “Traditionally, whoever could do the most vehicles on the same platform would win, but in this new world if you make a platform and believe you can keep it the same for 10 years, you will probably be dead in 10 years.”

In this new world, if you make a platform and believe you can keep it the same for 10 years, you will probably be dead in 10 years

Speed of development – the ability to get redesigned vehicles with new features to market faster than a competitor – will be the key differentiator between carmakers in the electric age, Green insists. And so far Tesla has yet to prove itself better than the automotive establishment; despite improvements in performance and range, its flagship Model S is fundamentally the same car it launched in 2012. Every single vehicle in Volvo’s current line-up is younger.

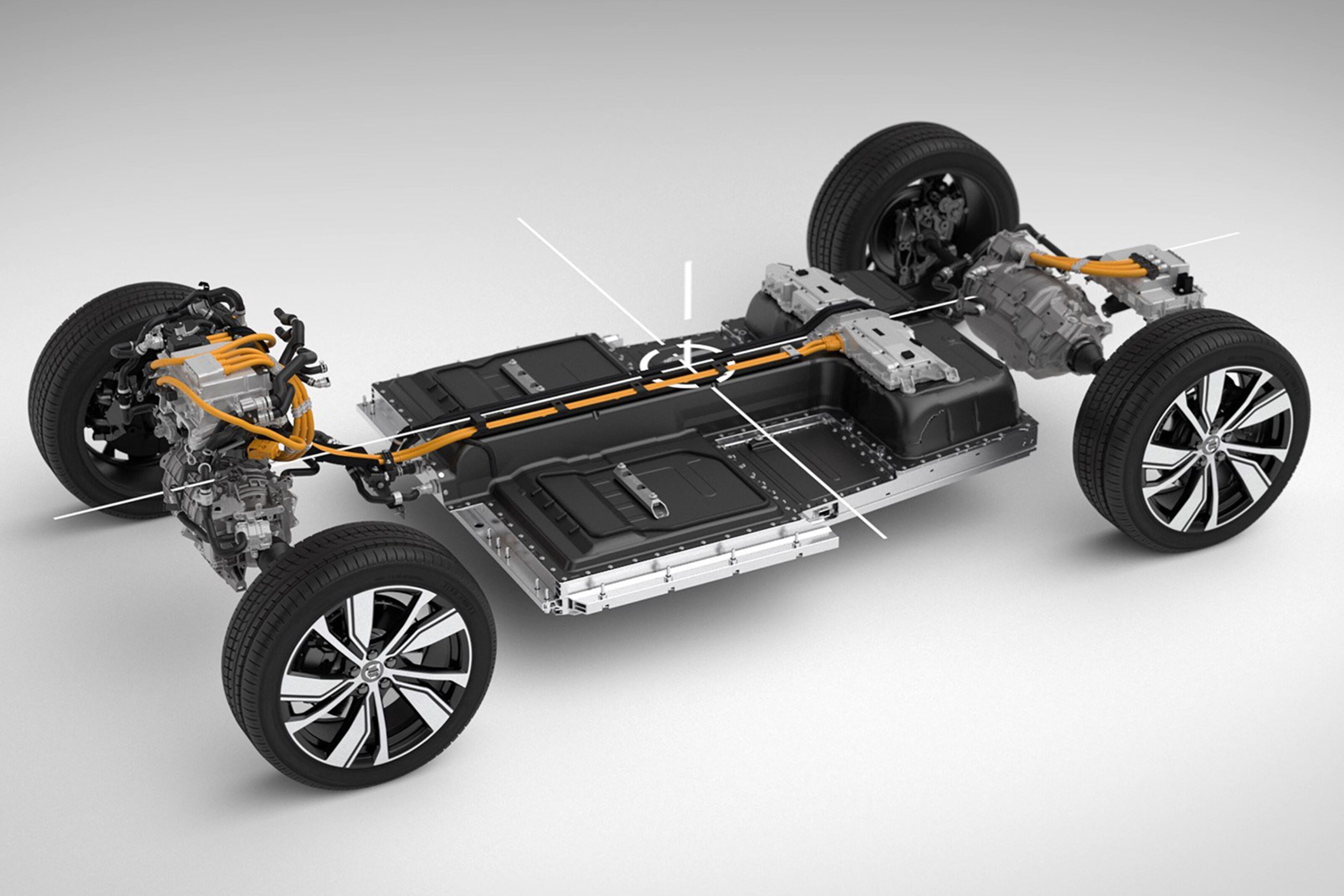

What’s more, Green believes the skateboard platform favoured by many electric vehicle start-ups is an inefficient solution in terms of both weight and packaging. Far better, he argues, to integrate battery cells directly into the vehicle’s body structure and use e-motors and inverters that are tailored to a vehicle’s performance and packaging parameters. That’s why Volvo, which has announced it will produce nothing but electric vehicles by 2030, has established its own battery lab, and is about to start designing its own e-motors with integrated inverters.

“We gain in electrical efficiency,” Green says. “We gain in space efficiency. We gain in weight efficiency. There are so many areas where we can still optimise what from the beginning looks like a fairly simple solution.”

The point is, Volvo isn’t the only legacy manufacturer that is pivoting to focus on electric vehicles. Billions are now being splurged on electric vehicle development by all the major legacy car makers, and Green believes the electric vehicle start-ups are going to need very deep pockets to stay in the game. “Our conclusion is that doing a brand-new electric vehicle is not going to be cheaper than doing a brand-new internal-combustion-engine vehicle.”

Tesla and the rest, you’re on notice: The empire is about to strike back.