Unless the world takes a massive and seemingly impossible U-turn in its environmental mindset, there will be no next-generation diesels, even if current diesel tech is tweaked to give it a few more years of commercial life.

The brick wall that diesels have run in to is built from ever-stringent exhaust emission regulations and reinforced by broader environmental policies. The future of internal combustion engines – what there is of it – lies with turbocharged petrol engines, in part designed and built with lessons learnt from current diesel technology.

The reason why you’re most likely driving a diesel now has its roots in Europe in the 1990s. In what was – now somewhat ironically – an environmentally driven European Union policy, diesel development was fostered due to its lower carbon dioxide (so-called greenhouse gas) production compared to equivalent petrol engines.

Diesel and petrol fuels produce roughly the same amount of carbon dioxide for each unit of fuel burnt, but diesels burn less fuel to do the same job so win on the greenhouse-gas count.

Carried by a range of EU-wide incentives, the take-up of diesel cars in the EU went from 22 per cent of new-car sales in 1997 to 50 per cent in 2005, and by decade’s end accounted for the majority of new-car sales in Europe.

The spill-over effect took longer to reach here but can be seen most graphically in today’s new 4x4s where petrol engines are very few and far between. Amongst the overwhelmingly popular 4x4-ute sector, there isn’t a petrol engine anywhere in a mainstream model.

The 1990’s environmental policy-driven preference for diesel laid the platform for the European automotive industry to work on developing diesel engines that could match the performance and refinement of petrol engines of the time.

Over time, the advances in diesel performance – especially in specific power output – have been phenomenal and have come off ever-more sophisticated turbocharging, increasingly higher-pressure common-rail injection, and piezo-crystal (and other fast-switching) fuel injectors, all controlled by smart electronics.

Before all this happened, things were very different, as a quick look back in time illustrates. Back in 1990, Toyota’s then all-new 3L diesel, first seen in the then-new (fifth-generation) Hilux was a 2.8-litre four. Two engine generations (and three model generations) down the track, today’s Hilux is again powered by a 2.8-litre four but one that’s very different from the 3L, the power and torque numbers telling a stunning story.

Where the 3L 2.8 made 60kW of power at 4400rpm and 183Nm of torque at 2400rpm, the current Hilux’s 2.8 makes 150kW at 3400rpm and 500Nm at 1600rpm to 2800rpm. So that’s that 2.5 times as much power and 2.7 times as much torque. And all the while, and most tellingly, the new 2.8 isn’t revving nearly as high as the old 2.8.

But, as in a late-night TV ad, there’s more to come. As impressive as Toyota’s new 2.8 might be against the old 2.8, the pointy end of current tech is even more advanced.

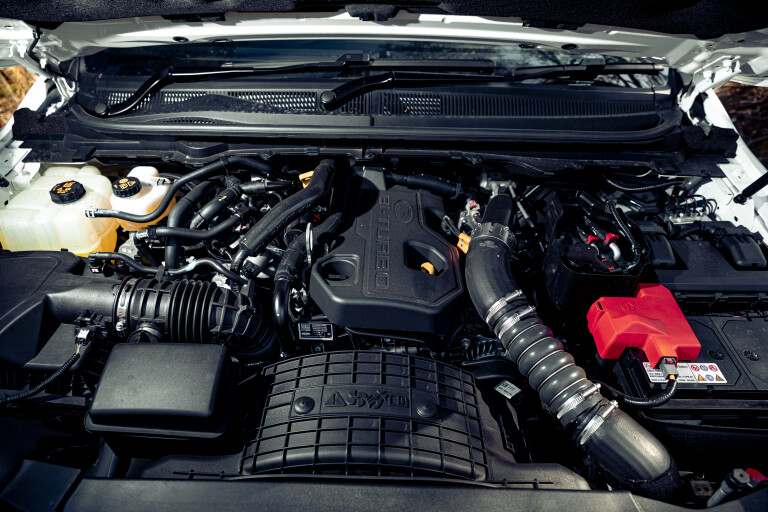

The current Ford Ranger, for example, has a 2.0-litre bi-turbo diesel that betters the current Hilux’s 2.8 for power (157kW vs 150kW) and matches it for torque (500Nm) despite being the better part of a litre smaller.

On a power-per-unit-of-capacity (specific power) basis that means Ranger 2.0-litre makes 3.5 times as much power as the 3L. And in terms of specific torque, it’s 3.8 times as much torque of the pre-diesel revolution 3L, a phenomenal, mind-boggling increase.

If you’re driving a bi-turbo Ranger right now, you would be shocked to get behind the wheel of a 3L Hilux … it would feel like two of your four cylinders had died and the third was almost dead. Hills that you couldn’t even see would slow down your 3L and have you reaching for a lower gear. Anything steep would soon have you down to a crawl. Believe me, I’ve been there. And it wasn’t pretty.

COMMENTS