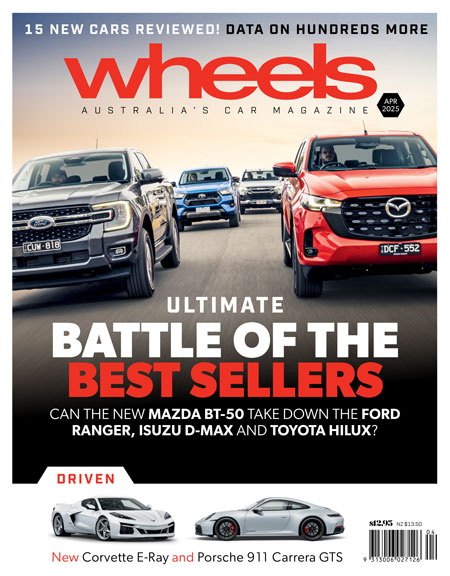

Australia’s favourite vehicles are dual cab utes. Year-on-year the Toyota HiLux and Ford Ranger battle it out for supremacy and in that sense, we’re not too different in the F-150-dominated United States.

No surprise that Australian politicians are keen to match the Yanks’ fuel efficiency standards, then.

The UK has been heading in the same direction as us, with record Ford Ranger sales in 2023. Instead of allowing these popular family-friendly four-door pick-ups to masquerade as work vehicles, they were set to be reclassified in the UK’s Benefit in Kind (BIK) rules – the company car scheme – as passenger, rather than light commercial vehicles.

It would’ve placed a Ford Ranger Wildtrak in the highest company car tax bracket of 37 per cent; from 2025 a 40 per cent taxpayer in the UK would have to cough up £582 ($1120) monthly for using it as a company car, compared to just £120 ($230) before.

A less polluting vehicle is taxed significantly less in the scheme. This is separate from the UK’s efficiency standards, though it drastically adjusts purchase habits.

Little surprise then that, around a week after the change was announced, pressure from the United Kingdom’s motor industry saw the government U-turn on its decision. The official reason is that the changes could have inadvertently harmed farmers and the UK’s economy.

Australia’s market is different from the UK’s, with utes necessary for large parts of our country where travelling long distances loaded or towing on rough roads is common.

But dual-cabs are now one of the default vehicles for Aussie families.

Statistics give credence to this, with Mitsubishi identifying that more than half of Triton buyers use their vehicles strictly privately: to and from work, on weekend drives and adventures.

These are the kind of buyers that see utes as a lifestyle vehicle for recreation, offering more than sheer utility.

I have no issue with how vehicles may be used, but giving concessions in the New Vehicle Efficiency Standards to Australia’s most popular and polluting vehicles by taxing them less than a Toyota RAV4 or MG ZS (according to the FCAI’s calculations) would only going to push more buyers into this type of vehicle – ergo more CO2 emissions in the short-medium term.

The Federal Chamber of Automobile Industries commissioned a study to determine the biggest winners and losers under the proposed tax penalties by the government’s proposed standards (the middle option) by 2025.

And while an Isuzu D-Max X-Terrain would be hit with a $2030 penalty (assuming the charge is $100 per gram), a Toyota RAV4 Edge 2.5 petrol suffers more at $2720. That doesn’t feel right.

Aside from the niche RAV4 Edge non-hybrid, Toyota is in a pretty good place with targets based on fleet average emissions. A Toyota RAV4 hybrid emits 31 per cent less CO2 than a 2.5 petrol and (with the right number sold) could aid in offsetting polluting LandCruisers, for example.

For manufacturers like Isuzu with its diesel-only line-up, the standards could prove tough.

Plug-in hybrids developed in tandem with other ute manufacturers could be the silver bullet for Isuzu and similar companies and Ford’s already on the program with Ranger.

While it’s logical to tax work vehicles under a different structure if they’re contributing significantly to industry, aligning increasingly private-use vehicles like high-spec dual-cabs more closely with passenger vehicles seems wise.

Australian automotive bodies caution that these policies will force large-scale changes within the sector, potentially affecting consumers.

But is there any point in implementing a toothless efficiency standard? After the warmest February on record, it’s clear the climate doesn’t wait for legislation.

We recommend

-

News

NewsVehicle emissions rules could save Australia billions, report predicts

A new report has revealed major savings for all Australian new car owners and the economy – if the government sets strong vehicle emissions mandates.

-

News

NewsNew vehicle emissions drop as peak bodies call for Government mandates

A small reduction in emissions year-on-year has been met with calls for greater action from the top

-

News

NewsFederal Budget: Real-world fuel emissions testing gets green light

The Australian Automobile Association says funding to carry our real-world fuel consumption testing is a huge win for Aussie families