By the end of the 1980s, only Nissan could have imagined the once-proud Zed name-plate still had anything going for it. For the rest of us, the badge was more or less reduced to joke status, plastered as it had been on some of the most ludicrous, pipe-and-slippers cars ever to leave a showroom.

This feature was originally published in MOTOR’s December 2004 issue

Oh sure, the whole Zed thing started with a bang with the 240Z of the rip-roaring 1970s, but after that point, she went a-sliding downhill on her increasingly fat ass.

A turbocharger in 1986 should have helped the car turn the corner (figuratively, if not actually) but all it really did was put back some of the performance that ULP took away.

A lot of car-makers would have taken this lot on board and dumped the badge, rather than risk tainting an all-new model with the same daft brush. But not Nissan. No siree, when it finally unveiled its new two-seat coupe, it hoped to ride out the public flogging and called it the – wait for it – 300ZX. Our breath was baited.

As it turned out, of course, the new car was about as much a real 300ZX (slack motor, goofy looks, blancmange suspension) as a fart in church is a real disaster. The new mill was sharper than ever before (apart from the rorty in-line six of the original 240 perhaps), it combined a decent ride with competent handling, and it looked a million bucks.

Indeed, it set a new benchmark in Japanese sports car design. At the time of its release, the Zed’s designers said they’d opted for the new look, but kept the old name in order to return to a pure sports car concept. They added that they felt the Zed brand had been softened – no duh.

In light of current model Audis and the New Beetle – and a bunch of other new metal bearing a roofline profile similar to the Harbour Bridge – the Zed was well and truly ahead of its time. It was big and wide and low, but it was the sweep of the window that really smacked you between the eyes.

The flush headlights and rounded bumpers were nice and aggressive and while it all looks a bit dated now, it can still look pretty sharp in the right colour (which isn’t black).

Like the exterior, there was a single knockout element to the interior, and that was the tweed trim that covered the transmission tunnel and half the door trims. It was, for many folks, either a master-stroke or a complete balls-up. We’re inclined to go with the former.

Personally? I didn’t hate it then and I don’t hate it now, although 15 years and gawd-knows-how-many kays later, it’s possibly going to be looking a tad second-hand.

The rest of the insides were pretty generic Nissan late 1980s fare, with clear instruments and decent standard equipment for the time. The seats weren’t too shabby either, grippy enough to support enthusiastic drivers, they are six-way adjustable. You can also count on air-con, cruise, central locking (no remote, though) full electrics and even a leather-clad steering wheel.

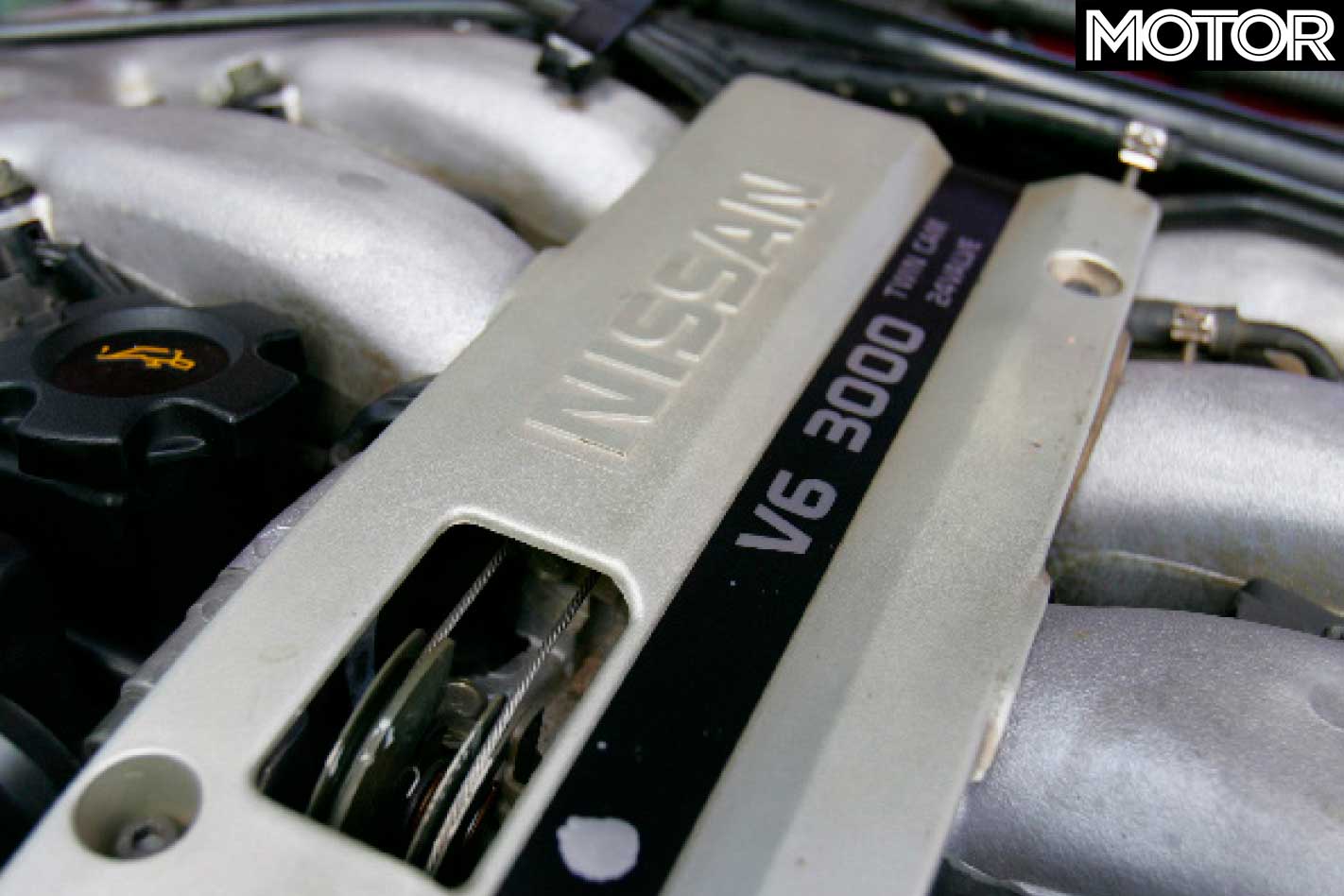

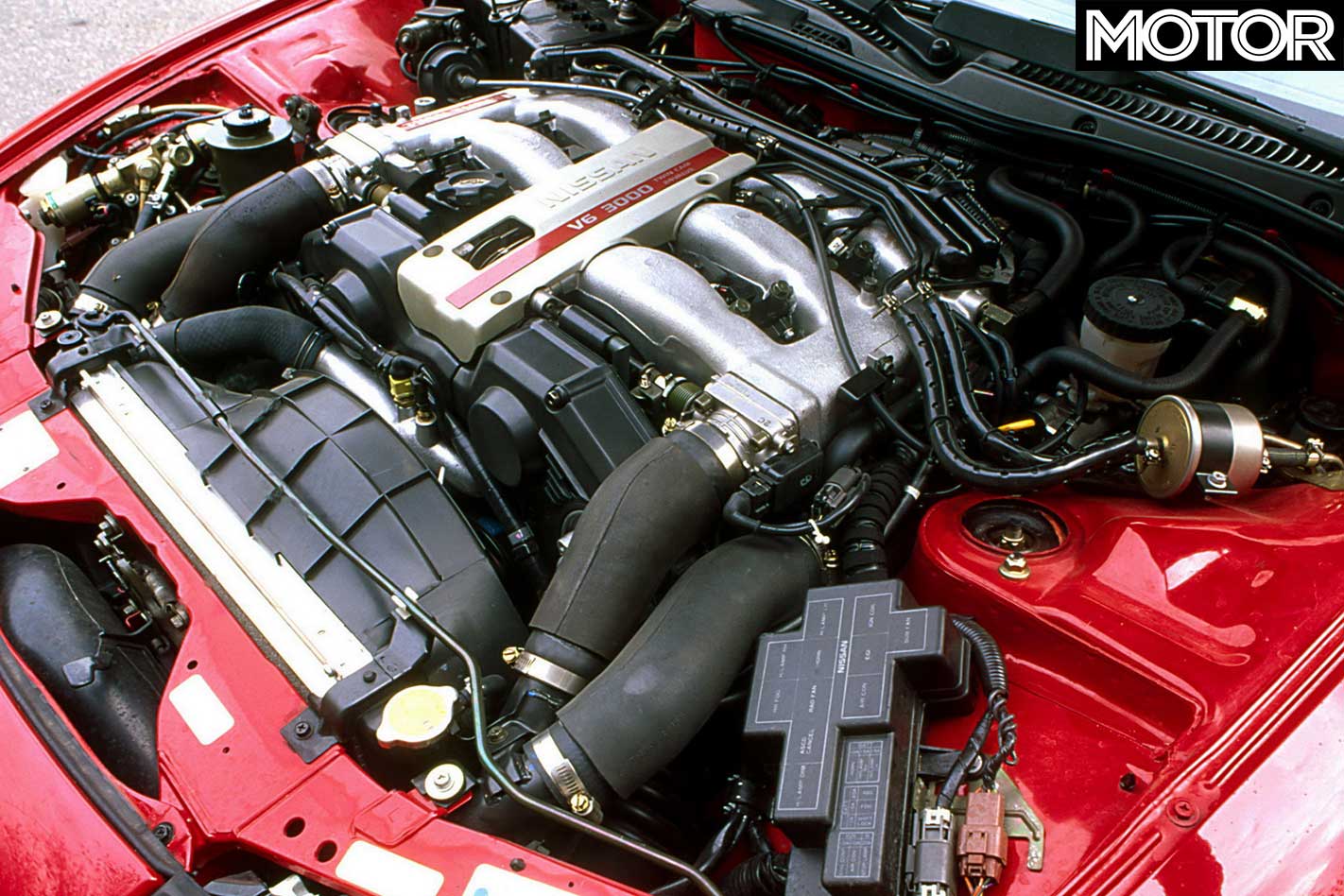

It might have looked pretty exotic, but under the skin, the ZX was a conventionally laid out piece of gear. The engine was in the front and drove the rear wheels via a gearbox in the usual place. The V6, while nothing to write home about now, was a bit of a Bobby-dazzler in its day. Better yet, it owed almost nothing to the yawn-inducing Zed cars of yore.

You need to remember that a V6 was still a bit special back in ’89, so when you add a 3.0-litre displacement, including twin overhead cams per bank, four valves per cylinder and electronic injection, you suddenly had a pretty marketable piece of iron on your hands. Ooh-er, we all went.

Compared with the previous version of the same engine, with its single cams per bank and turbocharger, the new mill made a fraction more power but a fair bit less torque. In the wash up, the new car made 166kW (155kW for the old turbo) and 269Nm (319Nm), which was enough to make it feel pretty good in a smooth, flowing kind of way.

What it wasn’t, however, was a real head-banger, thanks to the relatively hefty body shell it was toting around (1490kg to be exact) and the fact that it was tuned a bit on the mild side.

It could be very quick point-to-point, provided you kept the motor spinning, used the gearbox and got used to the feeling of being in a very wide car. Through the twisty stuff the big Zed displayed an impressive level of grip, although when pedalling hard it had a tendency to understeer.

The right foot would generally see it bring the nose in, though, and because of its weight it was never that twitchy in the rear. It had a pretty good ride for something this sporty and, overall, it was more grand tourer than ram-raider.

Buying a 300ZX these days is less of a lottery than it might be for other alleged sporty cars of the same age. Like a lot of Nissans over the years, the motor seems to be fairly bulletproof, although you need to be very wary of anything that doesn’t have some kind of a service record.

Manifold studs can crack over time, injectors have been known to fail on a random basis and the coil packs can give trouble in the longer term. None of those things are the end of the world, although drilling out a broken manifold stud is time consuming and labour intensive.

Other than that, watch out for any of the usual suspects when it comes to second-hand performance cars. You know the sort of stuff: warped rotors, hammered synchros, tired diffs and, of course, crash damage. Check inside the engine bay and make sure you lift all the carpets in your search for wrinkly metal that suggests a history involving a shunt or two.

Check the paint carefully, too, because some colours (whites and reds) had a fair bit of pearl in them and will be a bitch to match. The other thing to watch out for is a grey import.

Australian-delivered cars were only ever fitted with the 3.0-litre, atmospheric V6, so anything with the three-litre V6 twin turbo that was available in other markets is a grey import. But it’s not even that simple, because we’ve seen plenty of atmo 3.0-litres getting around that are also grey imports, so check the compliance plate to see whether it’s an Oz-delivered vehicle or not.

We wouldn’t dismiss a grey out of hand, but you need to be aware that they’re worth a bit less on the open market, so paying a non-grey price for a grey is, obviously, a hiding to nowhere.

On the other hand, prices don’t vary as much between grey and non-grey ZXs as they do, for instance, with 200SXs, but that could be because the Zed is worth peanuts these days anyway. A turbo 3.0-litre is likely to be ready for a set of turbo bearings by now, and check for a smoky or rattly engine that indicates it’s on its last legs.

When the 300ZX was released back in 1989, it cost the better part of $65k, these days it goes for a lot less and represents excellent value for money.

FAST FACTS 1990 Nissan 300ZX

BODY: 2-door coupe DRIVE: rear-wheel ENGINE: 3.0-litre V6, 24-valve DOHC POWER: 166kW @ 6400rpm TORQUE: 269Nm @ 4800rpm COMPRESSION: 10.5:1 BORE/STROKE: 87.0mm x 83.0mm WEIGHT: 1490kg POWER-TO-WEIGHT: 111kW/tonne TRANSMISSION: five-speed manual SUSPENSION: independent by unequal length upper and lower arms with coil springs and anti-roll bar (f); independent by multi-link with coil springs and anti-roll bar (r) L/W/h: 4525/1800/1255mm WHEELBASE: 2570mm TRACK: 1495mm (f); 1535mm (r) BRAKES: 280mm ventilated discs (f); 297mm ventilated discs (r) WHEELS: 16 x 7.0-inch (f & r), alloy TYRES: Dunlop D40 M2; 225/50 VR16 (f & r) FUEL: 72 litres, ULP PRICE: $62,950 (February 1990)

What we said?

“The new 300ZX has just enough of the old look about it to link it to its forebears. It has an impressively high level of adhesion and the new Zed’s speed-sensitive, power-assisted rack and pinion steering is sharp and precise. The 300ZX represents the latest in Japanese big sports car design. Its smoothly integrated design sets a new target for other makers to aim for.” James Cleary, February 1990