If there’s one thing Larry Perkins has learned in his long motorsport career, it’s to use the right tool for the job. The no-nonsense, six-time Bathurst 1000 winner was renowned for the reliability of his racecars and engines and was fond of saying there were “no palm trees” in his pits. That’s Larry-speak for no bullshit. At Perkins Engineering, function always came before flamboyance.

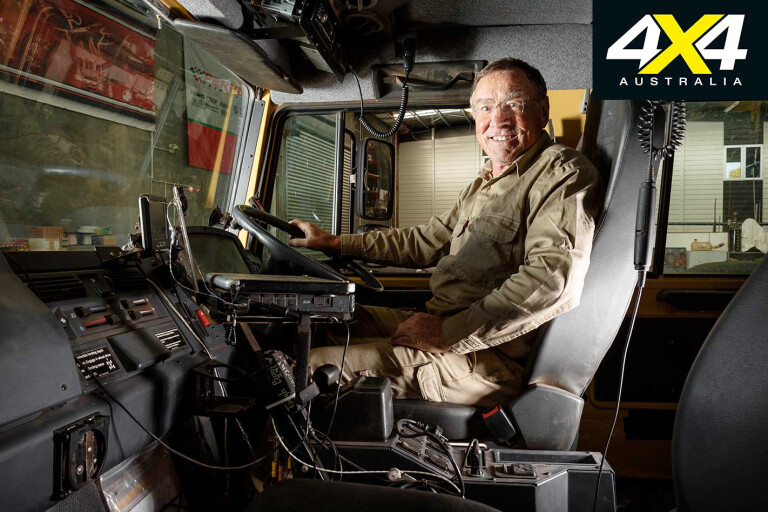

So when Perkins retired in 2011 to take up his other passion, exploring the deserts of outback Australia, he wanted a no bullshit, high ground clearance vehicle that could handle the extremes of terrain he would encounter, tow a trailer with his quad bike, and be comfortable enough to live out of for extended periods. So Perkins bought a Mercedes-Benz Unimog U4000 – naturally.

Perkins was already familiar with the big German 4x4 trucks and had built an off-road motorhome based on an earlier model, with a Kenworth truck cab in place of the ’Mog’s, which he still owns.

Perkins was already familiar with the big German 4x4 trucks and had built an off-road motorhome based on an earlier model, with a Kenworth truck cab in place of the ’Mog’s, which he still owns.

But it was a device Perkins developed for his new Unimog that would transform it into the V8 Supercar of off-road trucks, a Land Cruiser on steroids (but more on that later).

Aussie stamp

Eight months after he ordered it, the Unimog cab/chassis arrived – basically stock except for air-con and, most importantly, Mercedes’ onboard tyre inflation system – and Perkins set about modifying it into an Australian desert conqueror.

He jettisoned the “pathetic” single 160-litre fuel tank, replacing it with two tanks with a total capacity of 550 litres, and fabricated the rear cabin structure, adding storage bins and drawers all around the chassis to house everything from a kitchen to tool boxes, spares and bottles of red, of course.

Everything was designed to be light because any racer will tell you weight is the enemy of speed and fuel consumption. “I don’t like weight, I hate carrying stuff I don’t need to carry,” Perkins growls.

He added a 190-litre water tank that can be filled (from a bore, for example) by an electric pressure pump that also feeds a shower hose; and for a hot shower Perkins boils water in a stainless steel bucket and uses the pump to extract it.

“I had a 75-year-old professor and his missus travel with me once and she didn’t mind having a shower (by the side of the truck); I’m not going to carry a shower cubicle,” Perkins smiles.

Inside the ‘motel’ section of the ’Mog, which is mounted at three points, like the cab, to allow for 10 degrees of chassis twist, there’s a double bed with storage under it, various fridges and freezers and room to stow items like his satellite dish stand.

There are three solar panels on the roof making 450 Watts and the ’Mog has just about every electrical power configuration available: 12, 24 and 240 volts, and a 12- to 240-volt convertor.

The ’Mog is powered by a 160kW/810Nm 4.8-litre turbo-diesel four, and that surprised Perkins when he placed his order. “I would have preferred a six because they are inherently smoother. It’s got a lot of torque, but I wouldn’t mind another 50hp, especially when I’m towing my trailer. But with more power comes more fuel consumption.”

The high-tech, coil-spring suspension is “bog standard” and, combined with huge 395 x 20-inch tyres, the 7.1-tonne (fully loaded) ’Mog has a very soft ride. Changing tyres is not for the fainthearted, though, a wheel and tyre weighs a whopping 125kg!

Sophisticated all-disc brakes have dual calipers and four-channel ABS that can be deactivated off-road, and the big ’Mog can turn on a 10-cent piece. “I’ve got a 79 Series Toyota Land Cruiser and the Unimog has an almost 10-foot tighter turning circle, I couldn’t believe it,” Perkins marvels.

Perkins overdrive

The Unimog’s one drawback was its gearing, it’s too low for this wide, brown land. Perkins ordered a manual transmission which has electronic shift with pneumatic actuation and eight forward and six reverse gears, plus low range.

What transforms the Unimog, though, is the Perkins-designed overdrive which gives the truck 32 forward gears and 24 reverse gears in total. He designed it out of necessity, as he explained to Mercedes engineers who inspected it.

“I told them I’ve sometimes got to drive 2000km just to get to some scrub and I can’t do that at 80km/h; you’re a danger to everyone else on the road when they’re doing 100,” he reasoned. We tend to agree with him.

After a technical thumbs-up, Mercedes gave him permission to use its intellectual property, free of charge, and the overdrive is now manufactured for the aftermarket under the Perkins brand by the Claas Group in Germany, and as original Mercedes equipment. It’s a win-win result.

Ever the pragmatist, Perkins based his 21 per cent overdrive on an older, pre-electronic Mercedes unit. That meant the Unimog’s ECU didn’t have to be reprogrammed to make the overdrive work with its computer-controlled transmission, which would have cost millions.

“It was a relatively simple exercise to make different input shafts to fool the electronics,” Perkins explains. “I start the engine in non-overdrive then I can immediately go into overdrive, because I haven’t selected a gear.

“The overdrive is ahead of the gearbox which doesn’t know whether you’re in overdrive or not. But at start-up the computer knows the revs are wrong (if you start in O/D) because a sensor on the input side of the gearbox tells the computer it’s not doing the right revs (450 instead of 650rpm) and a red light comes on. It takes about 10 seconds to get used to [the procedure].

“You don’t need overdrive until you want to split gears, so on the highway I normally get to seventh, which peaks at 69km/h, then I go into 7.5 (seventh plus O/D) which gives me 85km/h, then go out of O/D and back to eighth, which gives me over 90 then O/D which gives me 110km/h. I’ve had 117km/h out of it. And it’s all just a flick of a switch and a clutch depression.”

Simpson simply

The Unimog really comes into its own when Perkins hits his beloved deserts and not much stands in its way. The daunting sand hills of the Simpson were a snap.

“I crossed 40 to 50 sand hills towing my quad bike, ahead of my brother in a Toyota, and I was doing it easier, probably because I was able to get the right tyre pressure quicker than he could. I’d run down to 10psi for bigger sand hills (25psi is normal) and as soon as I crested a hill I’d start pumping them back up which takes about three minutes. And you can do that on the fly.”

On the highway Perkins gets a remarkable 24L/100km at 100km/h in overdrive, and those extra gears also transform outback driving; the ’Mog averaging 31L/100km crossing the Simpson Desert on the Madigan Line at 15 to 20km/h.

“I found that gear 3.5 was the ideal ratio in the sand hills,” Perkins says. “Fourth was a little too fast and the engine power wasn’t enough, and third was a bit slow with a surplus of overdrive.”

Perkins loves his no-bullshit Unimog which has done 97,000 trouble-free kays.

“In some ways it’s the top of the tree for off-road four-wheel driving. It handles very well, and I say that as an ex racecar driver. The Binns Track from Alice Springs to Old Andado has got some beautiful winding roads and you can drift through there at 80 or 100km/h, it’s fantastic,” Perkins grins. “Not that I recommend that, being politically correct.”

* Contact Perkins Engineering via Facebook to enquire about purchasing a Perkins Unimog overdrive locally.

Finding Barclay

Larry Perkins is proud of his racing achievements, but you get the feeling he is even more proud of finding a long lost cache of equipment, abandoned in the Simpson Desert in 1904 by explorer and surveyor Henry Vere Barclay.

“A lot of people have won Bathurst, but not many have done something like this,” Perkins smiles.

Although Barclay, a former Royal Navy captain, and his second-in-command Ronald Macpherson, had kept an expedition journal complete with the coordinates of where they left their gear, no one had been able to find it. That intrigued Perkins, so he and his brother Peter set off in the Unimog last year to find the Barclay stash.

“I didn’t go by what was written (in the journal) at all,” Perkins explains. “I could see from his daily readings that he was wandering around up there and walking about 18 to 20 miles a day. I was able to determine a rough path where he should have been walking, which didn’t make any sense to the spot where he said he left the gear. So I chose not to even look there and put a spot on a map, and after four-and-a-half days on the quad bike we found the gear within five kays of that spot. I was pretty chuffed about that.”

Barclay and his three-man team were seasoned explorers but were in deep trouble by the time they abandoned their gear, including water tanks, cooking gear, ammunition, personal effects and even glass photography plates.

“One had severe cramps and the others were concerned about whether they were going to make it,” Perkins says. “They had camels, but they had to walk. They were heading south-west, they’d got past the middle, but they didn’t realise the sand hills were so big. It was 114˚F (46˚C) and they didn’t have enough water. The camels couldn’t cross the sand hills so they unloaded everything except for rifles, theodolite and food because it was a five-day walk out of the Simpson Desert to water.

“Barclay and Macpherson were experienced men and knew what they were doing, but why would they carry three pick axes? On that first trip we recovered over 200kg of goods and on the last trip we got it all, about another 100kg of gear.”

So, did the expedition appeal to Perkins’ risk-taking racer side or to his problem-solving engineer’s brain?

“A bit of a combination of everything,” he admits. “Having studied his diary over many weeks, this probably fits into ‘I need a bit of can-do’ attitude.

“But the homework of choosing a particular spot to go to (to start the search) has given me the greatest satisfaction and it was the combination of enthusiasm, can-do, logic, and just because others couldn’t do it, that made it a bit more exciting.”

COMMENTS