Nissan’s long-awaited new Navara is finally here. It’s called the NP300, or D23 in Nissan-speak.

The Navara joins the newly-released Mitsubishi Triton MQ, a model designation once used by Nissan for its Patrol.

All this is pure coincidence. What counts is that the vibrant ute market has been given its first major shake-up since the arrival of the new Ford Ranger/Mazda BT-50 twins and the Volkswagen Amarok back in 2011.

The NP300 replaces both the D40 Navara and the older D22 Navara and is the first all-new Nissan ute in 10 years. At this stage only three four-wheel-drive models are available, all of them dual-cabs with factory tubs, but more 4x4 variants with single and extended cabs, including cab-chassis models, will be here by year’s end.

The new MQ Triton replaces the MN Triton that arrived in 2009, itself a development of the distinctly-styled ML Triton of 2006. MQ 4x4 variants include three dual-cab utes and single- and extended-cab cab-chassis models.

The new MQ Triton replaces the MN Triton that arrived in 2009, itself a development of the distinctly-styled ML Triton of 2006. MQ 4x4 variants include three dual-cab utes and single- and extended-cab cab-chassis models.

To get a measure on the new Navara and new Triton, we have lined them up against the standard-setters in the class: the Volkswagen Amarok and the Mazda BT-50. In this case the Mazda also represents the almost mechanically identical Ford Ranger. The Ranger and BT-50 differ in styling, pricing and some details, however they effectively drive and perform the same.

For this dual-cab test we aimed for the popular mid-spec automatics, which we got with the $43,490 Triton GLS and the $50,890 BT-50 XTR. However, we had to settle for the new base-spec $45,990 Amarok Core and a top-spec $54,490 Navara ST-X (prices do not include on-road costs).

But the specification consideration isn’t important here, because we are looking at how the respective utes perform both on and off the road, which has more to do with the mechanical package than equipment levels.

To see how they went, read on…

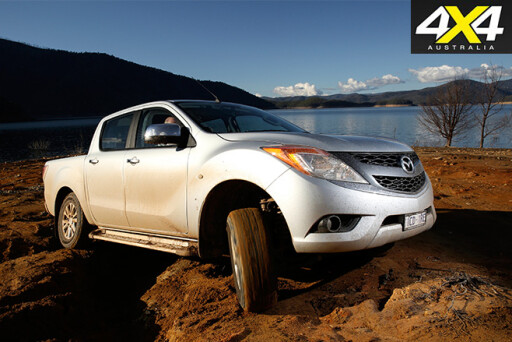

MAZDA BT-50

When the then new BT-50 appeared in late 2011, it shared nothing with the previously named BT-50. In fact, where the original BT-50 was actually a Mazda, the current BT-50 owes more to Ford, because, along with the Ranger, it was largely designed and developed by a global Ford team headquartered at Ford Australia.

When the then new BT-50 appeared in late 2011, it shared nothing with the previously named BT-50. In fact, where the original BT-50 was actually a Mazda, the current BT-50 owes more to Ford, because, along with the Ranger, it was largely designed and developed by a global Ford team headquartered at Ford Australia.

Mazda had an engineering team on hand and had input in the core development, and then went its own way with the details (see sidebar).

The BT-50 is a big ute in more ways than one. In this company it has the biggest engine, it claims the most power and torque, it has the longest wheelbase, it’s the heaviest and it has the highest Gross Vehicle Mass (GVM). All of this generally works in its favour, but not always.

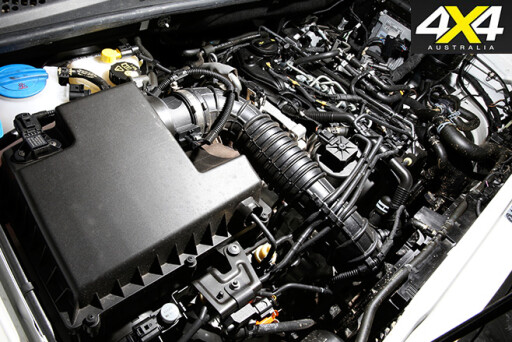

Powertrain and Performance

The BT-50’s 3.2-litre five-cylinder turbodiesel is a Ford-designed unit first used in the Transit delivery van.

Why five cylinders, you ask?

Why five cylinders, you ask?

Well, it’s simple. A five-cylinder engine generally runs smoother than a similar-capacity four-cylinder engine, especially with engine capacities greater than 3.0 litres. Bigger fours can be harsh at higher engine speeds, where a five is smoother.

This advantage, however, doesn’t play out here, because Mazda’s ‘big’ 3.2-litre five is up against much smaller fours, the biggest of which is Triton’s 2.4-litre. It is no smoother in general running and, being a five, it has the disadvantage of a somewhat lumpy idle, something that’s not a problem with a four-cylinder. The 3.2 is not a particularly quiet engine, either, in this company.

Aside from its extra cylinder, the Mazda’s engine also stands out here, as it makes its maximum power at notably lower revs than all the others and doesn’t need or like to be revved as hard.

It’s also in the lowest state of tune, making just 46kW per litre compared to the VW’s 66.5kW per litre and the Nissan’s 61kW per litre, something that may help with longevity.

Despite its ‘lazy’ low-revving and soft-tune nature, the ‘big’ five-cylinder still claims the highest power and torque figures and provides competitive performance despite having to propel the heaviest ute.

It’s not the fastest ute here, but it’s not the slowest either. In fact, there’s little between the four in terms of straight-line performance. The Mazda does, however, use more fuel than any of the others, according to both the ADR figure (9.2L/100km) and our testing figure (12.0L/100km).

It’s not the fastest ute here, but it’s not the slowest either. In fact, there’s little between the four in terms of straight-line performance. The Mazda does, however, use more fuel than any of the others, according to both the ADR figure (9.2L/100km) and our testing figure (12.0L/100km).

For its part, the Mazda’s six-speed auto mates well to the torquey, low-revving nature of the engine, and offers generally smooth, ‘intelligent’ and well-timed shifts. It’s the pick of the two BT-50 gearboxes, because the six-speed manual has a vague and awkward shift action, something that will hopefully be fixed with the BT-50’s imminent mid-life makeover.

Ride and Handling

One thing that Mazda (and Ford) got particularly right with their shared platform some five years back are the on-road dynamics. The Mazda’s chassis has a slightly ‘sportier’ tune than the Ranger’s, but this is hard to notice unless you drive the two back-to-back.

Either way, this is a good ute to steer, with a positive road feel and surprisingly tidy handling despite its leaf-sprung live axle at the rear and load-carrying suspension tune.

But the Mazda does have limitations, when compared to the other utes. On poor quality roads with marginal and constantly changing traction, the full-time 4x4 systems of the Triton and Amarok (selectable in the case of the Triton) offer more drive and reassurance, with the convenience of being able to use 4WD regardless of the road surface.

But the Mazda does have limitations, when compared to the other utes. On poor quality roads with marginal and constantly changing traction, the full-time 4x4 systems of the Triton and Amarok (selectable in the case of the Triton) offer more drive and reassurance, with the convenience of being able to use 4WD regardless of the road surface.

The Nissan also has conventional part-time 4x4 like the Mazda, but the Nissan’s coil-sprung rear end gives better drive out of corrugated corners and the like.

Off-Road

The BT-50 continues to perform strongly off-road thanks to its torquey engine, good clearance and effective traction control system. All BT-50 4x4 variants also come standard with a driver-activated rear locker, which adds another level of off-road performance.

On the negative side, the Mazda does feel bigger than the other utes here, especially the Triton and the Navara. Its wheelbase, for example, is a full 220mm longer than that of the Triton, so it’s less manoeuvrable in tight situations.

Unlike the Navara and the Amarok, the Mazda draws its engine intake from the inner guard, which gives good protection from water entering the engine.

Unlike the Navara and the Amarok, the Mazda draws its engine intake from the inner guard, which gives good protection from water entering the engine.

It also has the best theoretical wading depth of the four, at 800mm. Like most utes, the Mazda doesn’t have a recovery hook at the rear, but there is one positioned at the front.

Cabin, Comfort & Safety

The BT-50 has a big and comfortable cabin, but only the steering-wheel tilt can be adjusted and not its reach. There’s a spacious rear seat, with only the Amarok among these four, offering more shoulder room for three and also more headroom, especially for the two outside passengers. The BT-50 does, however, have more combined front and rear legroom than the Amarok.

The mid-spec BT-50 tested here is generally well-equipped, but the dashboard screen is too small and its controls are too fiddly. In some ways, the interior is starting to feel old. Hopefully this is another thing to be addressed with the BT-50’s mid-life revamp in October. The BT-50 has the highest five-star ANCAP safety rating.

Practicalities

The BT-50’s ‘working’ credentials are as good as it gets here. It has a class-leading 3500kg maximum tow capacity and excellent payload figures thanks to its 3200kg GVM. That it’s also the heaviest ute here somewhat diminishes the advantage of the GVM figure, in terms of payloads, though.

The factory tub is also a good size, but no BT-50 has a 12-volt outlet in the tray and the standard tie-down hooks would be more useful if they were mounted lower in the tray.

Other positives include a neat factory towbar arrangement (much better than the Ford Ranger’s), good support from the aftermarket industry. It also has parts that are interchangeable with those of the Ranger.

Mitsubishi Triton MQ

In creating its new MQ Triton, Mitsubishi didn’t set out to tackle head-on the new breed of big utes, such as the Ranger, BT-50 and Amarok. Instead, it has looked to the formula that was successful with the previous MN and ML Tritons and worked from there.

In creating its new MQ Triton, Mitsubishi didn’t set out to tackle head-on the new breed of big utes, such as the Ranger, BT-50 and Amarok. Instead, it has looked to the formula that was successful with the previous MN and ML Tritons and worked from there.

What Mitsubishi has effectively done is taken the previous MN Triton, pulled it apart, and then put it back together with either new or revised parts. Most notably, it has an all-new engine, a new six-speed manual gearbox, a new transfer case, tweaked suspension and a slightly bigger and far more polished cabin.

The five-speed automatic that was previously only available on the top-spec GLX-R model is now available on lower-spec models, relegating the old four-speed auto to history.

Powertrain and Performance

The all-new 2.4-litre turbodiesel in the Triton is a typically modern, twin-cam, 16-valve, four-cylinder diesel with high-pressure common-rail injection and what looks to be a surprisingly big variable-geometry turbo.

What’s not very typical is the fact that this new engine makes its maximum torque at 2500rpm, a very high figure for a modern turbodiesel. By way of comparison, Nissan claims the Navara’s maximum torque is on tap by 1500rpm, while the Amarok’s and the BT-50’s maximum torque arrive well below 2000rpm.

In fact, the BT-50 makes its maximum power just 500rpm above where the Triton makes its maximum torque. Such is the disparity between the ‘grunty’ BT-50 and the ‘revvy’ Triton.

In fact, the BT-50 makes its maximum power just 500rpm above where the Triton makes its maximum torque. Such is the disparity between the ‘grunty’ BT-50 and the ‘revvy’ Triton.

You particularly notice the Triton’s off-idle and low-rpm softness with the new and sweet-shifting six-speed manual gearbox, but the auto, as tested here, effectively masks this characteristic via its torque converter, which allows the engine to pick up rpm more quickly than the manual does.

The Triton’s engine is noticeably smooth and quiet and, helped by the fact that the Triton is the second lightest ute here, offers performance that is competitive despite not being a front runner in terms of on-paper power and torque.

The Triton has an older auto with fewer speeds than the others and, while it doesn’t do a bad job, it’s generally not as agreeable as the other three autos, all of which offer quicker, smarter and more decisive shifts.

Despite a very good ADR fuel figure of 7.6L/100km (the second best figure here), the Triton fell back a little when put to the sword in the real world, with its 11.5L/100km test average.

Ride and Handling

With its sporty steering and relatively tidy handing, the previous-generation Triton was a standard-setter in its day. Thankfully, these strengths live on in the new Triton, which has been improved with revised front suspension and longer springs at the rear. The longer leaf springs are there to help soften the unladen ride (without compromising load-carrying), but the Triton still rides a little harder at the rear than the others. Perhaps its shorter wheelbase plays a part here.

In this company, the Triton is unique thanks to its ‘Super Select’ 4x4 system, which brings all the benefits of full-time 4x4 to general touring on wet bitumen, and to gravel and dirt roads.

In this company, the Triton is unique thanks to its ‘Super Select’ 4x4 system, which brings all the benefits of full-time 4x4 to general touring on wet bitumen, and to gravel and dirt roads.

On this test we had on-and-off-again rain, plus a wide variety of road surfaces to traverse. So being able to select full-time 4x4, rather than having to shift between high-4 and 2WD – as was the case with the part-time 4x4 Mazda and Nissan – was a real bonus.

Off-Road

Super Select is also handy on easy trails, because you can use high-4 with the centre diff open in situations where the traction is generally good and you don’t need locked fore and aft drive. If it gets more slippery, it’s just a matter of turning the Super Select dial one notch to lock the centre diff. Another turn of the dial will then engage low-range.

What the Triton doesn’t offer at this spec level is a rear-locker, even as an option. That only comes with the top-spec Exceed model, but even then it’s not as sophisticated as the lockers in the Mazda, Nissan or VW. That’s because it cancels traction control across both axles, not just the rear axle.

This knocks the low- and mid-spec Tritons down a notch in its off-road capabilities. It’s still more than handy, however, with decent clearance, good forward vision and the benefit of being the smallest ute here with the best turning circle.

This knocks the low- and mid-spec Tritons down a notch in its off-road capabilities. It’s still more than handy, however, with decent clearance, good forward vision and the benefit of being the smallest ute here with the best turning circle.

A change from the previous generation Triton is that the engine air intake comes via the inner mudguard rather than from under the bonnet lip, which is good move. Mitsubishi is, however, still conservative with its wading-depth claim of 500mm, or 600mm, if you keep below 5km/h. Again, it’s a typical ute, with no rear recovery hook, but two at the front.

Cabin, Comfort & Safety

The new Triton cabin is slightly bigger than before, but it’s still the smallest cabin in this company, and it’s certainly cosy for three adults in the back.

However, the cabin’s fit and finish is far better than before, with more of a passenger-car feel than that of a commercial vehicle. The driver can now also adjust the tilt and reach of the steering wheel.

The much-criticised front seats in the previous model have also been improved, but have still met mixed reactions from our testers. Our shorter drivers gave them the thumbs up, while taller drivers gave them the thumbs down.

The much-criticised front seats in the previous model have also been improved, but have still met mixed reactions from our testers. Our shorter drivers gave them the thumbs up, while taller drivers gave them the thumbs down.

One annoying thing that all drivers noted is that the rear tub and its sports bar stood out and could be quite distracting in the rear-view mirror, or when shoulder-checking.

In recent tests, the new Triton achieved the highest five-star ANCAP safety rating.

Practicalities

The Triton’s relatively short wheelbase means that almost the entire tub is behind the rear-axle line, which is not ideal for carrying heavier loads. The tie-down hooks in the tub are also mounted too high.

The Triton has the lowest GVM here, but its relatively light weight helps redress the balance in terms of payload. Its 3100kg-towing capacity is also short of the class leaders, but is still adequate for decent-sized caravans, big boats and double horse floats. Being a new-design ute, the range of aftermarket enhancements will also be limited for the immediate future.

The Triton has the lowest GVM here, but its relatively light weight helps redress the balance in terms of payload. Its 3100kg-towing capacity is also short of the class leaders, but is still adequate for decent-sized caravans, big boats and double horse floats. Being a new-design ute, the range of aftermarket enhancements will also be limited for the immediate future.

Nissan Navara NP300

Nissan’s NP300 Navara is almost new from the ground up and represents a number of ‘firsts’ for a mainstream Japanese ute. Most notably the ST and ST-X spec models now have a new 2.3-litre, four-cylinder diesel engine with two turbos; a feature in this class previously reserved for the Volkswagen Amarok.

Nissan’s NP300 Navara is almost new from the ground up and represents a number of ‘firsts’ for a mainstream Japanese ute. Most notably the ST and ST-X spec models now have a new 2.3-litre, four-cylinder diesel engine with two turbos; a feature in this class previously reserved for the Volkswagen Amarok.

All dual-cab variants (including 2WD models) also have a coil-sprung live axle at the rear, which replaces the leaf-spring live axle used in the previous Navara – and generally used across the ute market. The arrangement uses five links, two upper trailing arms, two lower trailing arms and a Panhard rod.

In designing the new NP300, Nissan has also bucked the trend to build a bigger ute. In fact, the NP300 is slightly smaller and lighter than the D40 it replaces. Compared to the D40, it is 41mm shorter and rides on a 50mm-shorter wheelbase. It’s also close to 100kg lighter than the D40 (top-spec models) and its GVM has been reduced from 3010kg to 2910kg.

However, importantly for bragging rights at the very least, its maximum towing capacity has been increased from 3000kg to 3500kg, bringing the NP300 into line with the class leaders.

Powertrain and Performance

The idea behind two turbos, rather than one, is not so much to produce more power, but to improve the spread of power – something you’ll quickly notice while driving this new Navara ST-X.

A single-turbo design is always a compromise between minimising lag and producing decent power, but by using two turbos this compromise is largely overcome (see ‘Power of Two’ sidebar).

A single-turbo design is always a compromise between minimising lag and producing decent power, but by using two turbos this compromise is largely overcome (see ‘Power of Two’ sidebar).

Thanks to its sophisticated sequential turbo arrangement, the Navara’s full measure of 450Nm is available at just 1500rpm, yet the engine also likes to rev and doesn’t hit peak power until 3750rpm.

The engine is both responsive at low revs and punchy at higher revs. This, combined with the seven-speed auto and the Navara’s relatively light weight, pushes the NP300 to the front of the pack in terms of straight-line performance.

For its part, the auto is generally agreeable, but the shift protocols seem more skewed towards economy than performance, which can often have you switching to the gearbox’s ‘manual’ mode for better control in more demanding driving situations.

The engine is also smooth and generally quiet, except under load where it does become noticeably noisy.

The engine is also smooth and generally quiet, except under load where it does become noticeably noisy.

It has good fuel economy, too, although its on-test consumption figure of 11.2L/100km (second in this group) fell well short of its remarkably good 7.0L/100km official ADR figure.

Ride and Handling

The Navara’s coil-sprung rear end doesn’t ride any more smoothly than its leaf-spring competitions here, but the general control and stability it affords is better, especially when driving through and out of bumpy and corrugated corners. It’s a pity the Navara doesn’t also offer some sort of full-time 4x4 to further press home this advantage.

While the Navara is a generally sweet-handling ute, the overall chassis response is compromised by heavy, slow and lifeless steering. It’s somewhat akin to the feel you get with under-inflated front tyres.

While the Navara is a generally sweet-handling ute, the overall chassis response is compromised by heavy, slow and lifeless steering. It’s somewhat akin to the feel you get with under-inflated front tyres.

Off-Road

In this company, the Navara is a mixed bag off-road. On the positive side its low first gear and deep low-range reduction produces the lowest crawl ratio of 44.6:1, which for an automatic is excellent. What’s more, the shift protocols of the seven-speed work well off-road, something you couldn’t say of the seven-speed auto behind the V6 turbodiesel in the D40.

Both the top ST-X spec and the mid ST spec NP300s also come standard with a rear locker and, like the lockers on the VW and the Mazda, when its engaged it doesn’t cancel the electronic traction control across the front axle.

Not so good is that the engine’s air-intake has been moved from the inner mudguard to adjacent to the top of the radiator, and the claimed wading depth is now a low 450mm, something that owners may want to address with a snorkel.

Compared to the other utes here, the NP300 also rides a little lower and was always the first to bottom out off-road, an issue that will be familiar to D40 owners.

As is the norm with most utes, there isn’t a recovery hook at the rear, although there is one up the front.

Cabin, Comfort & Safety

The Navara has the most car-like cabin here, though some of that comes down to the fact that it’s the only top-spec model tested and is loaded with equipment.

The cabin is, however, quiet regardless of speed and road surface, thanks to good NVH control and low wind noise. The previously mentioned engine noise under load is an on-going issue, though.

The cabin isn’t as big the Amarok or the BT-50, something which rear-seat passengers will especially notice, although the Navara’s rear seat does a better job of seating three than the Triton.

Notable cabin exceptions include no reach adjustment for the steering wheel and no centre headrest for the rear seats.

Notable cabin exceptions include no reach adjustment for the steering wheel and no centre headrest for the rear seats.

On the flip side, the NP300 is unique among utes as the ST-X spec has a sunroof, while all NP300s have a small power-operated opening rear window.

The NP300 has achieved the full five-star ANCAP safety rating.

Practicalities

As mentioned, the Navara now matches the best in class with its 3500kg tow rating and, while the GVM is among the lowest two here, the fact that the Navara is the lightest helps with payloads. ST-X-spec Navara’s also have Nissan’s handy adjustable tie-down system in the tub.

What is also noteworthy is that, while all the utes here require servicing at least every 12 months, the Nissan can go for 20,000km between services, a benefit for high-mileage Navara buyers. Meanwhile, the VW and Mitsubishi both need servicing every 15,000km, while the Mazda has a 10,000km service interval.

Finally, while this ST-X has 18s with relatively low-profile tyres, the 16s off the other NP300 variants can be fitted if you want a more durable higher profile tyre.

Volkswagen Amarok

Volkswagen’s Amarok was the first of the new generation of utes that make up the current market. It was launched abroad in 2010 and arrived here in the first quarter of 2011, about six months before the Ford Ranger and Mazda BT-50 twins. It was initially available only as a six-speed manual, with the eight-speed automatic not arriving until the following year.

Volkswagen’s Amarok was the first of the new generation of utes that make up the current market. It was launched abroad in 2010 and arrived here in the first quarter of 2011, about six months before the Ford Ranger and Mazda BT-50 twins. It was initially available only as a six-speed manual, with the eight-speed automatic not arriving until the following year.

In most ways, Volkswagen followed a standard ute design, with a separate chassis, double-wishbone coil-sprung front suspension and a leaf-sprung live axle at the rear. However, VW added a notably large cabin and a big tray, which set it apart from the other utes of the day.

The 2.0-litre bi-turbodiesel and the eight-speed auto also seemed somewhat left field, although the engine was already in VW’s stable (powering things like the Transporter Van), while the auto gearbox was a propriety unit from prolific German transmission specialist ZF and was already in use by a number of different car companies.

Since its release, the Amarok range has been revised a few times, the engine specs tweaked and the equipment details changed. What you see here, however, is essentially the same Amarok that’s been here since day one.

Powertrain and Performance

The Amarok has the smallest engine here, but, thanks to its bi-turbo arrangement, still offers competitive power and torque. On the road, the Amarok actually offers the best initial kick-down response, thanks to its fast-shifting close-ratio eight-speed auto, and it does this despite being the second heaviest ute here.

The Amarok also stands out for its willingness to rev despite also being strong off-idle. It’s also the smoothest, quietest and most refined engine here, something that’s no doubt helped by its relatively small capacity.

The Amarok also stands out for its willingness to rev despite also being strong off-idle. It’s also the smoothest, quietest and most refined engine here, something that’s no doubt helped by its relatively small capacity.

The eight-speed automatic is also the best gearbox here in terms of shift quality, shift speed and shift timing. It also combines with the engine to produce a powertrain that’s difficult to fault. Topping things off, the Amarok proved the most fuel efficient on test (10.8L/100km) despite a mid-field ADR figure of 8.3L/100km.

Ride and Handling

The Amarok’s chassis carries on the same polished performance of the engine and offers the best steering, road feel and general handling. The full-time 4x4 system then adds extra security and grip on demanding road surfaces including bumpy and wet bitumen, corrugated gravel, and dirt roads.

In most ways, when compared to the other three, the Amarok feels more passenger car than ute. Buyers wishing to have more of a passenger car and less of a ute ‘feel’ can opt for the softer-riding ‘Comfort’ springs at the rear. These are available on Trendline, Highline and Ultimate Amaroks, but not on the base Core model as tested here.

In most ways, when compared to the other three, the Amarok feels more passenger car than ute. Buyers wishing to have more of a passenger car and less of a ute ‘feel’ can opt for the softer-riding ‘Comfort’ springs at the rear. These are available on Trendline, Highline and Ultimate Amaroks, but not on the base Core model as tested here.

Off-Road

On paper, the Amarok, with its single-range 4x4 system, shouldn’t work in steep and slow-going off-road conditions, but it does. With the eight-speed gearbox having a low first gear and a surprisingly effective torque convertor, we have never had a problem climbing steep off-road inclines either in this test or during all the other testing we have done with Amarok autos during the past three or four years.

What’s more, its 4x4 system is more than clever as you go from cruising down the freeway, at whatever speed you choose, straight on to a steep off-road climb, without touching a button or a lever. The Amarok is always in 4x4, its centre diff locks by itself, and it doesn’t need low range; not that there aren’t buttons to tweak the off-road performance, if you so wish.

Most importantly, all 4x4 Amaroks have a driver-switch rear locker. There’s also a switch for the very effective down-hill descent control and to tweak the ABS and the stability- and traction-control system’s off-road conditions, which is handy but not essential. There’s a separate switch to disable the stability control to help in sand or deep mud.

Most importantly, all 4x4 Amaroks have a driver-switch rear locker. There’s also a switch for the very effective down-hill descent control and to tweak the ABS and the stability- and traction-control system’s off-road conditions, which is handy but not essential. There’s a separate switch to disable the stability control to help in sand or deep mud.

The Amarok’s auto is also the pick of the four gearboxes when off-road in both full-auto mode and when used manually.

One caveat here: we’ve never towed a heavy camper trailer in steep off-road conditions with the auto. Those wishing to do so may be better off with the manual Amarok, because it has dual-range gearing (see ‘4x4 Dilemma’ sidebar).

All Amaroks draw their engine intake air from adjacent to the top of the radiator and the official wading depth is a modest 500mm, which makes the Amarok another candidate for a snorkel.

The Core does, however, come fitted with decent all-terrain rubber in the form of Pirelli Scorpion ATRs. It’s also the only ute here with a rear recovery hook, while the front has a screw-in towing eye.

Cabin, Comfort & Safety

The Amarok has a big, spacious and comfortable cabin that’s understated in typical German fashion, especially so in this base-Core spec. But it does offer the best front seats, tilt and reach steering wheel adjustment for the driver, and the roomiest back seat for three adults.

All the controls are also logically and simply laid out, but the Core misses out on the 12-volt outlet on the dash top, which is fitted to all other 4x4 models and is handy for accessory sat-navs and the like.

The Amarok has a maximum five-star ANCAP safety rating.

The Amarok has a maximum five-star ANCAP safety rating.

Practicalities

The Amarok has a biggest tub here and well-placed tie downs, but the Core doesn’t have the 12-volt outlet in the tub, which is standard on all other variants.

All Amaroks, including single cabs, come with a factory tub, but this is a delete option ($1500 saving) on everything but Highline and Ultimate. This seems like a very logical approach to splitting the range between cab-chassis and ute models.

The Amarok has the lowest tow rating here – a still-decent 3000kg – while its 3040kg GVM is bettered only by the Mazda. If the previously mentioned ‘comfort springs’ are fitted to the rear, the GVM is reduced to 2820kg, which is still not too far short of the Triton’s 2900kg or the Navara’s 2910kg.

THE VERDICT IS IN...

Dual-cab utes perform a wide variety of roles, which is a key reason why they are immensely popular in the overall new-car market. They can be used as day-to-day family transport, weekend 4x4 fun machines, work trucks, or serious 4x4 tourers. And most are used in some combination of these roles.

Dual-cab 4x4s are so popular that they have eclipsed 4x4 wagons in sales and now compete against much cheaper small, passenger cars in overall sales. Like the USA, Australia is becoming a nation that loves ‘pick-up trucks’.

Dual-cab 4x4s are so popular that they have eclipsed 4x4 wagons in sales and now compete against much cheaper small, passenger cars in overall sales. Like the USA, Australia is becoming a nation that loves ‘pick-up trucks’.

The multitude of roles that dual-cabs fulfil makes it hard to pick an outright winner in any comparison, this one included. It just depends on what you want out of your dual-cab 4x4.

You wouldn’t buy one of these utes over the other because of performance alone.

There’s not a significant difference here. Nor would you be likely to buy one over the other for the differences in payload or towing capacity, unless you really needed the full 3500kg tow rating offered by the Mazda and the Navara.

If you are after value for money, it’s hard to go past the Triton. Consider this: the cheapest way to get into any of these four dual-cab utes is via the Triton GXL manual, at $36,990. At the other end of the range, the cheapest way to get into one of these utes with luxuries like leather and sat-nav is via the $47,490 Triton Exceed.

The Triton also offers dual-range full-time 4x4 at just $40,990 for the GLS manual, where the cheapest way to get full-time 4x4 in an Amarok is via the $45,990 Core auto, and neither of the other utes offer full-time 4x4.

On the downside, the Triton has the smallest cabin, the lowest GVM, the least sophisticated automatic gearbox and a short wheelbase that is as much of a disadvantage as it is an advantage.

The Mazda’s strength lies in its cabin size, and its high GVM and tow ratings. It also stands out in a world where downsizing is the name of the game in diesel engines. In the past 10 years, Triton has gone from 3.2 to 2.4 litres while in one generation the Navara has gone from 3.0 or 2.5 litres to 2.3 litres.

The Mazda’s strength lies in its cabin size, and its high GVM and tow ratings. It also stands out in a world where downsizing is the name of the game in diesel engines. In the past 10 years, Triton has gone from 3.2 to 2.4 litres while in one generation the Navara has gone from 3.0 or 2.5 litres to 2.3 litres.

Even the new HiLux due to be released later this year has a smaller 2.8-litre diesel replacing the current 3.0-litre diesel. And the Amarok has always had a small engine.

The benefit of the Mazda is that its ‘big’ engine is relatively low-revving and has the lowest specific power output, both of which augur well for longevity. Proof of the soundness of the Mazda’s overall design is that it can still hold its head up against the newer utes here and has the benefit of an imminent update to come.

Nissan spared little with its new Navara NP and it impresses with its new engine and ’box, it’s general car-like refinement and its generally solid off-road ability. Model for model, it’s also sharply priced, even if it’s not as cheap as the Triton.

Given the sophistication of the engine and gearbox, it’s a shame, however, that Nissan didn’t back this up with an on-demand (effectively full-time) 4x4 system as used in the previous-generation Pathfinder and the Y62 Patrol. It would have been much better for it.

The NP300 could have been a game changer, but it isn’t. And a few details like the revised engine air intake, ground clearance (especially at the front) and the doughy steering are disappointing. But you still get a lot of ute for the money and the top-spec ST-X is very well equipped, with a sunroof and all.

As ever, the Amarok is one of the more expensive utes, but it does most things better than any of its opposition and is simply a delight to drive both on and off the road. It offers real passenger-car refinement, but it’s still big, tough and off-road capable.

As ever, the Amarok is one of the more expensive utes, but it does most things better than any of its opposition and is simply a delight to drive both on and off the road. It offers real passenger-car refinement, but it’s still big, tough and off-road capable.

We’d like to see the auto gearbox and full-time 4x4 system offered with dual-range gearing, but not because the current system does anything wrong. In fact, it works brilliantly.

It’s our current ‘Best in Class’ champion and that position is still intact despite the two new utes here. As editor Raudonikis quipped during this test: “The Amarok is in a different class to the other three utes here … a class above.”

Click here to read the full range review of the Volkswagen Amarok.

COMMENTS