Want to feel ancient? Well, consider this.

Temporally speaking, the launch of the E31 BMW 8 Series was closer to the first televised appearance of Elvis Presley than it is to today.

But then, the 8 Series is a car that has a rare ability to catch you off guard. Despite none finding customers during the ’80s, it’s viewed by many as a quintessentially ’80s BMW – yet the technology that underpinned this car was anything but a throwback.

Its genesis can be traced back to the mid-’80s. In the early ’80s, ex-Ford and Audi stylist Pavel Hušek was commissioned by BMW design chief Claus Luthe, to submit early proposals for a flagship coupe.

By 1985, the E24 6 Series coupe had been on sale for a decade, having been facelifted in 1983.

Rather than reach for a new lexicon of design language, Hušek, probably best known for his work on the Skoda Favorit and Honda Beat, reimagined Paul Bracq’s E24 6 Series as sleeker and more aerodynamic, while retaining much of the classic form factor. It was deemed not radical enough by BMW’s board and rejected.

By 1985, the E24 6 Series coupe had been on sale for a decade, having been facelifted in 1983. It had also just enjoyed its greatest period in motorsport, having claimed the European Touring Car Championship twice, DTM once, both the Australian Touring Car Championship and the Australian Endurance Championship as well as a brace of victories in the Spa and Nürburgring 24 Hours events.

Yet behind the scenes, the requirements for its successor were coalescing rapidly.

It became apparent that this would not to be a like-for-like replacement. The boom era of the ’80s demanded something far more ambitious, something that would elevate the brand beyond anything that rivals Mercedes-Benz could counter.

Sporting aspirations went out of the window. Rather than some sort of snarling factory lightweight, the new car needed to be a showcase for BMW’s technological reach.

Luthe was the man overseeing what became the E31 project. Like all good bosses, he knew how to delegate, tasking rising star Klaus Kapitza with the styling of the exterior and Hans Braun with the cabin architecture.

Unfortunately, Luthe’s tenure with BMW was cut short after he fatally stabbed his 33-year-old son Ulrich during a family dispute on Good Friday in 1990.

The man who designed the Audi 50 (a design which went on to become the original VW Polo), the NSU Ro80 and the BMW E36 3 Series was sentenced to 33 months behind bars.

The budget for the E31 project was vast, rumoured to have been around 1.5bn Deutsche Marks, so expectations for the car were similarly elevated. Not only was it the first production car designed using CAD (Computer Aided Design) but it also pioneered the use of CAN-bus tech, effectively the car’s central nervous system, enabling communication with a number of ECUs throughout the vehicle.

Discrete nodes such as the engine, the transmission and the brakes could now transmit data frames to all other nodes using a robust and simple electrical architecture. The effect was to make what was previously impossible relatively straightforward.

Suddenly you could have a Sport button, for instance, which sharpened up a whole host of vehicle attributes. Yes, the 8 Series was the first to feature such a fitment.

That was far from the end of the innovations. The 8 Series was the first car to feature a six-speed manual gearbox attached to a V12 engine, a pairing which is all sorts of right. It was also the first to have active rear steer, a co-development between BMW and Bosch called Aktive Hinterachskinematik (AHK) as an option.

The standard 850i featured the clever Integral Rear Axle, which featured an elastokinematic multi-link rear end to induce a degree of passive rear steer. This aided stability but was always subject to phase shift, a reactive delay that reacts to what has happened rather than what is happening.

By the time the car arrived in Australia in late 1990, it wore a sticker price of $222,000

Fitting the rear axle with a computer-controlled electrohydraulic actuator which could actively steer the rear wheels was a game changer, but development on AHK wasn’t the work of a moment, finally arriving in 1991 as an option, and fitted as standard to the 1992 850CSi was introduced which had AHK as standard equipment so the AHK introduction is often linked to that of the 850CSi. In many regards it was a precursor to electronic stability control, improving vehicle stability at speed.

The 8 Series’ official debut was at the 1989 Frankfurt Motor Show. BMW’s usual billing of ‘The Ultimate Driving Machine’ was quietly replaced by the tagline for the big coupe; ‘The Supreme Synthesis of Technology and Design’.

By this stage the cost of the project, build planning and market expectations had combined to give the E31 an eye-watering price tag in many markets. By the time the car arrived in Australia in late 1990, it wore a sticker price of $222,000 plus on-roads. Adjust that for inflation and it’d be a half-million-dollar car today.

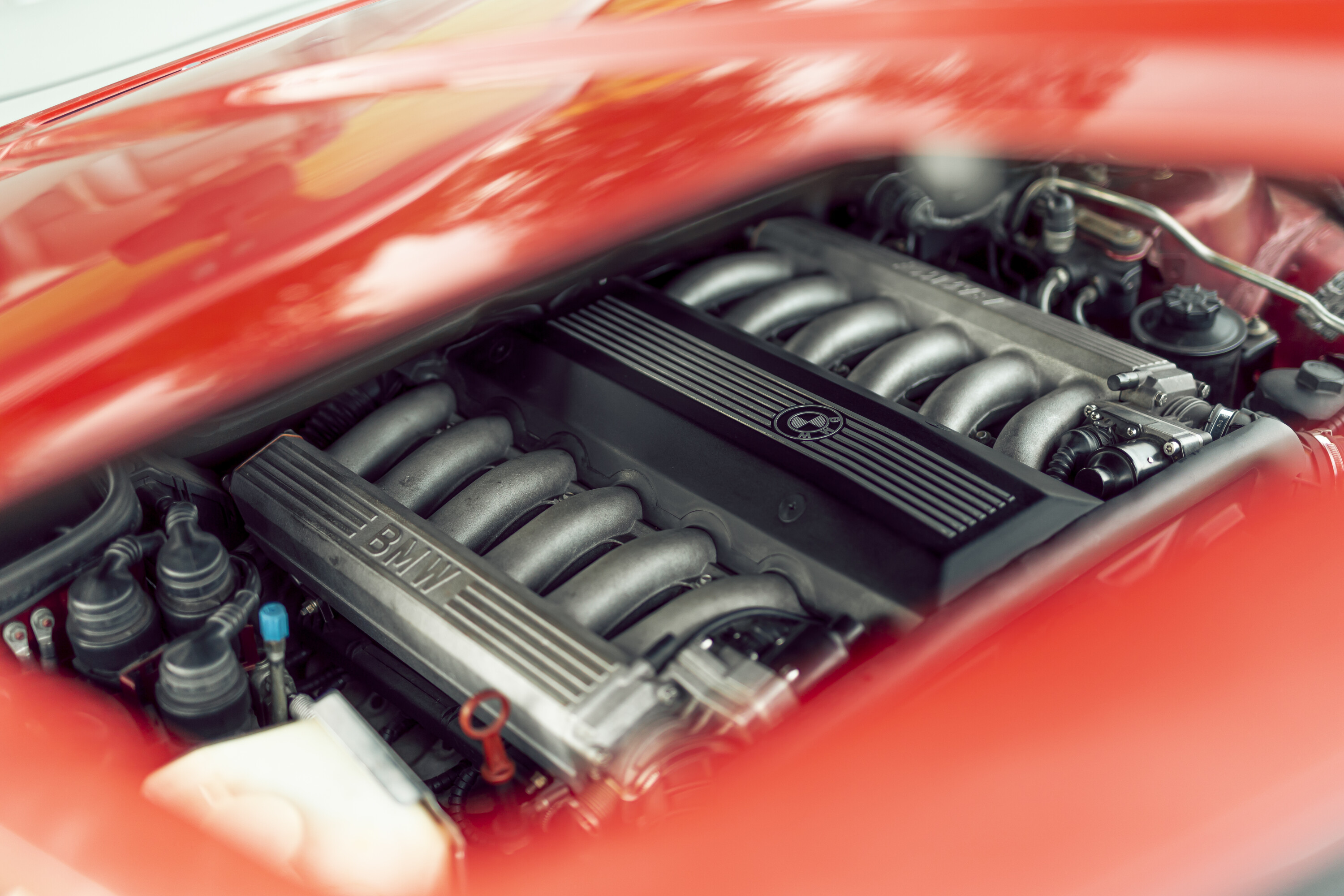

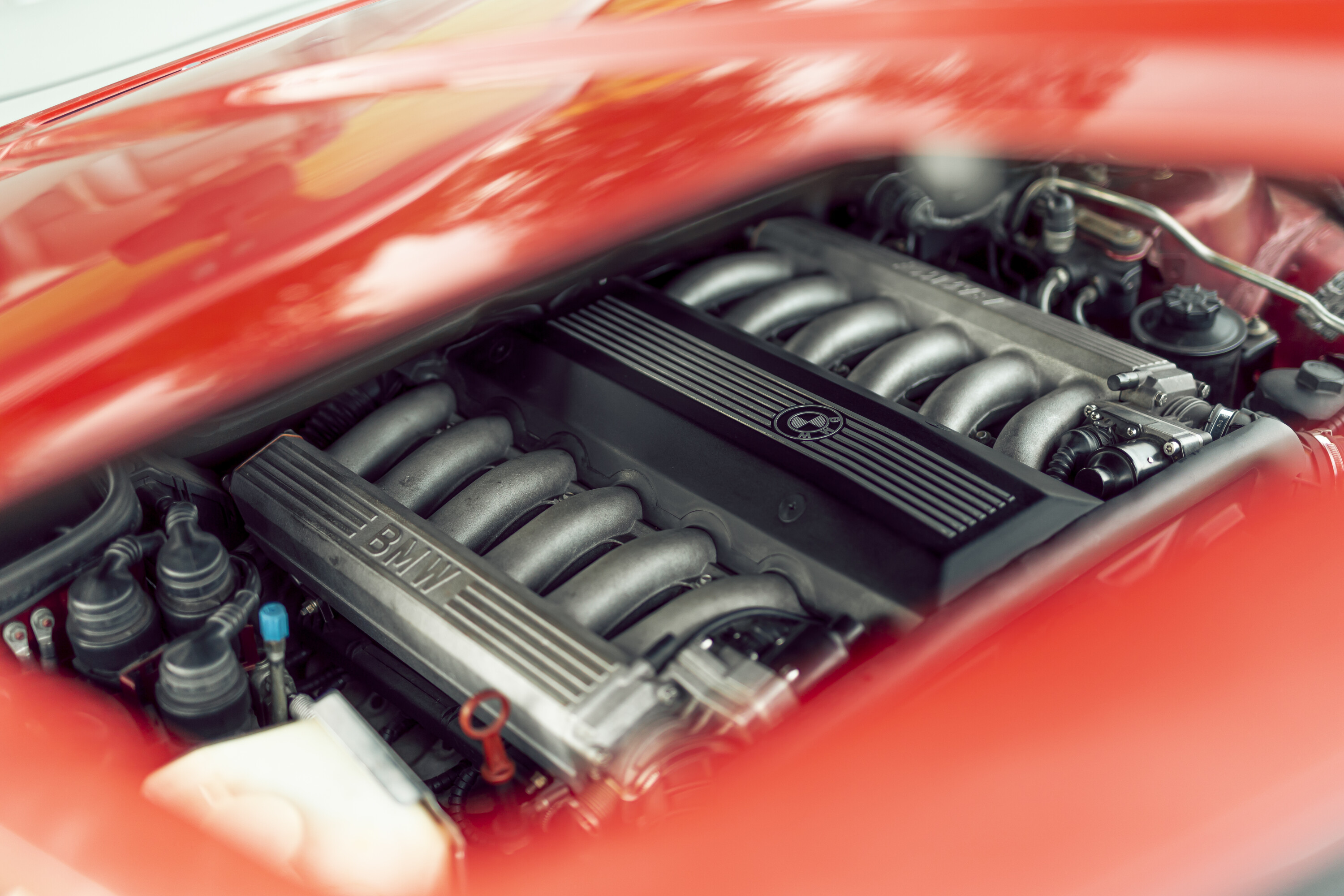

Initially, the E31 was a one-car deal; the 850i powered by a 220kW 5.0-litre V12 being the sole choice.

This M70 engined model (later called the 850Ci) made up fully two-thirds of the total E31 production figure of 30,621 units. The second most popular variant was the eight-cylinder 840Ci, with the 4.0-litre M60 engine accounting for 4728 units and the more powerful 4.4-litre M62 successor mopping up 3075 sales.

Between 1994 and 1999, the 850i was treated to a 5.4-litre M73 V12, good for 243kW, while the flagship model was the 850CSi, sold between 1992 and 1996, which utilised the 277kW 5.6-litre S70 V12 mated to a six-speed manual gearbox – an M car in all but name. These accounted for 1218 and 1510 units respectively.

The rarest of all the production E31 models was also the humblest. The 830i, built between March and July 1992 used a 3.0-litre M60 V8 engine. It’s even rarer now than it was in 1992 because all 18 prototype cars were destroyed by BMW, who felt that 160kW was perhaps a bit of a knee-jerk response to sales that were dipping as a result of tough market conditions.

The Gulf War had seen oil prices soar and the Japanese bubble economy had collapsed. The ‘greed is good’ years of ’80s excess had vanished and it was rapidly apparent that BMW’s huge investment into the 8 Series was never going to pay back.

Other rarities? There were 24 8 Series cars built under licence at BMW’s Rosslyn plant in South Africa. Then there are the Alpina B12 Coupe versions. These came in two distinct flavours: the B12 5.0-litre and the B12 5.7-litre, which were, perhaps unsurprisingly, spun from the 850i and 850CSi, respectively.

The B12 5.0 featured a lightly breathed-on M70 V12 generating 261kW which drives through a four-speed automatic box. The B12 5.7 retained the 850CSi’s three-pedal set-up but its bored block was good for a hefty 310kW and 570Nm. These remain the most sought-after roadgoing versions of the E31.

Even today, the 8 Series is an arresting proposition. It’s not one of those cars that has never dated – just that it has dated interestingly.

Whereas a modern 8 Series is all curves, complexity and bellicosity, the E31 is a simpler shape, the absence of the B-pillar focusing the eye on the organic shape of the glasshouse and the way the chamfered box arches swell into a low, flat rear end that suggests enormous potency, like a cartoon bottle rocket.

This impression is helped by a low front end that carries the eye the length of the car via a rising beltline and the subtlest of Hofmeister kinks in the rear side window. It can look slightly underwheeled by today’s standards, but then so does the current M4, a car which also lacks the redeeming feature of pop-up headlamps.

Buying an E31 requires patience and rewards no little perseverance.

Most cars will have some sort of damage to their plastic nose-cones and check wheel-arches, brake lines, door bottoms, sunroof panels and the leading edge of the bonnet for rust. Both the V8 and V12 engines are relatively tough units.

Early V8 engines had trouble-prone Nikasil liners but any issues with these should have been sorted a long time ago by now. Check for misfires, usually attributable to ageing lambda sensors or throttle bodies that are out of sync. It’s best not to run an E31 on fully synthetic oil as it tends to be too thin and is consumed quickly.

Don’t let water levels drop either, as this can cause air locks that will destroy the head gasket. Engine ancillaries such as the viscous fan, water pump and cam-cover gaskets are hotspots for failure and are usually larger jobs than they appear. Check suspension bushes and dampers as a front-heavy two-tonne car tends to chew through them.

The bravery and ambition of the 8 Series cements it to a time and a place while lending it a lasting significance

The key issue to keep an eye open for is electrical integrity. Remember, this was a first stab at CAN-bus technology and while the concept has proven sound, the initial execution resulted in a few teething issues with the many ECUs within the car that can and do fail and are not cheap to replace.

Pixels on the LED displays often fail and a botched HID headlamp upgrade (the standard dip beam lamps are jaw-droppingly feeble) can create a cascade of electrical issues. Finally, at no point should you jump-start an 8 Series with a flat battery without some form of spike protection as this can sizzle multiple ECUs instantly.

It can seem daunting, buying a German car with this amount of complexity, and it should. There are some cars that are an easy recommendation for those who want a hands-off modern classic, but the E31 8 Series is not one of them.

Owners claim that the rewards are well worth the investment in time, money, research and effort.

In managing to make the Mercedes-Benz SEC look positively antediluvian, BMW succeeded in its quest to establish technological superiority over its key rival. Today, that faded one-upmanship doesn’t count for too much.

Yet the bravery and ambition of the 8 Series cements it to a time and a place while lending it a lasting significance. That’s the mark of a great classic and it’s entirely likely that the 8 Series’ best days are still ahead of it.

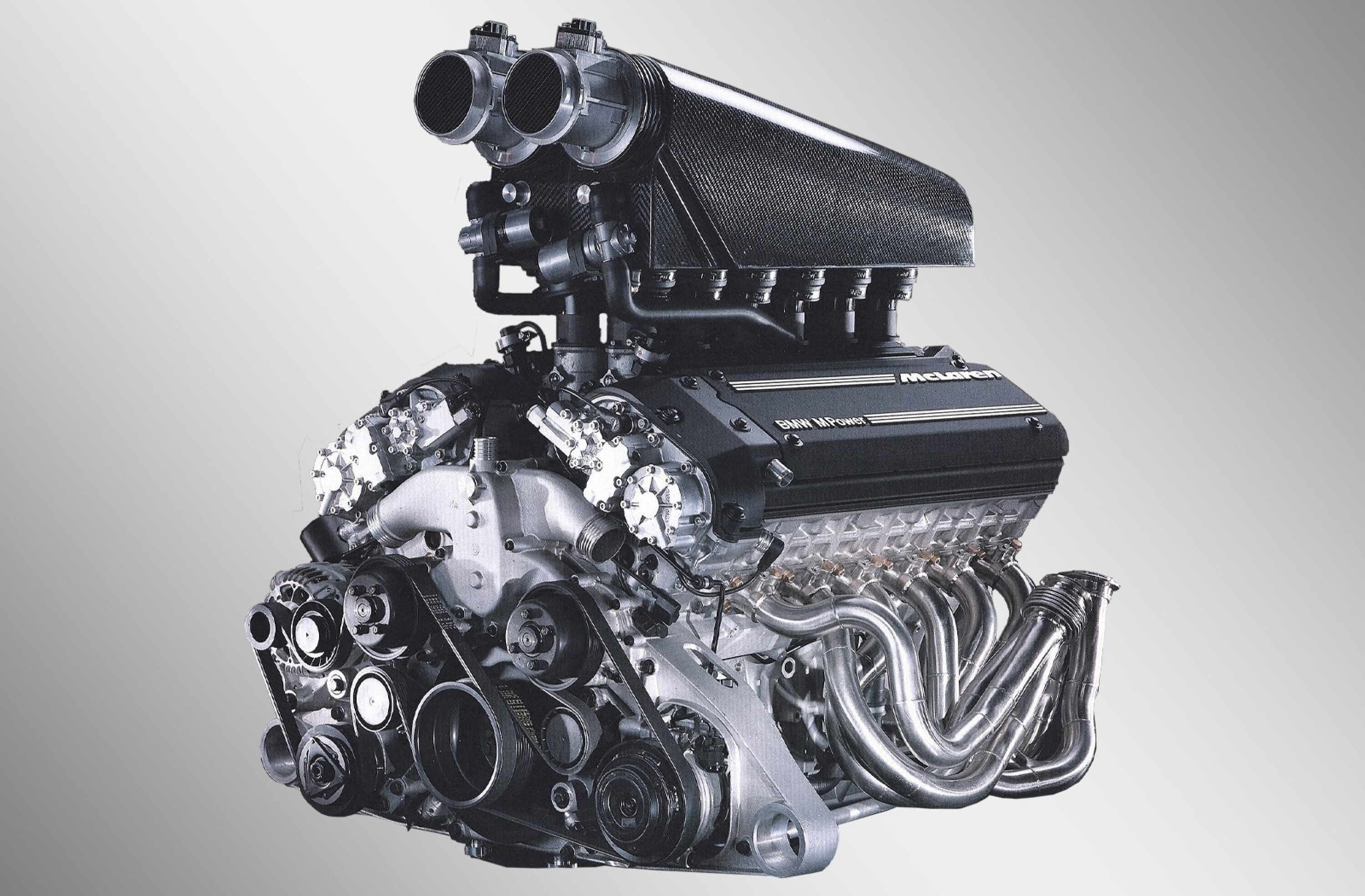

Was the stillborn M8’s engine donated to the mighty McLaren F1?

Not exactly. BMW completed a skunkworks project in 1991, developing an M8 prototype with a 410kW S70/1 V12 and next-gen chassis tech. Unlike the engine that would end up in the production 850CSi – a 5.6-litre S70B56 unit – the S70/1 featured two cams per bank of cylinders, 48 valves and a capacity of 6064cc.

Contrary to popular opinion, this was not the engine that powered the McLaren F1.

BMW engineer Paul Rosche approached Gordon Murray to enquire about supplying an engine and Murray confirmed that the S70/1 was too large and too heavy.

After much reworking, the Motorsport division’s final engine, the S70/2, met Murray’s 600mm length requirement, but it overshot the weight target by 16kg. Given that it was 6.4 percent too heavy but exceeded McLaren’s power requirement by 14 percent, it got the green light from Murray.

| BMW E31 850i specifications | |

|---|---|

| Engine | 4988cc V12, sohc, 24v |

| Max power | 220kW @ 5200rpm |

| Max torque | 450Nm @ 4100rpm |

| Transmission | 4-speed automatic |

| Weight | 1790kg |

| 0-100km/h | 6.3sec (claimed) |

| Price (now) | from $55,000 |