Excluding concepts and one-off oddities, the rarest M3 of all came not from Munich but from Queensland, courtesy of Frank Gardner Racing.

In a joint venture with BMW Motorsport, FGR built 15 E36 M3Rs to homologate the car for local endurance racing.

Porsche found enough customers to justify importing the 911 RS CS, while Mazda’s skunkworks was whipping up the RX-7 SP, so Gardner and his crew set to work developing the E36 into a potent racer.

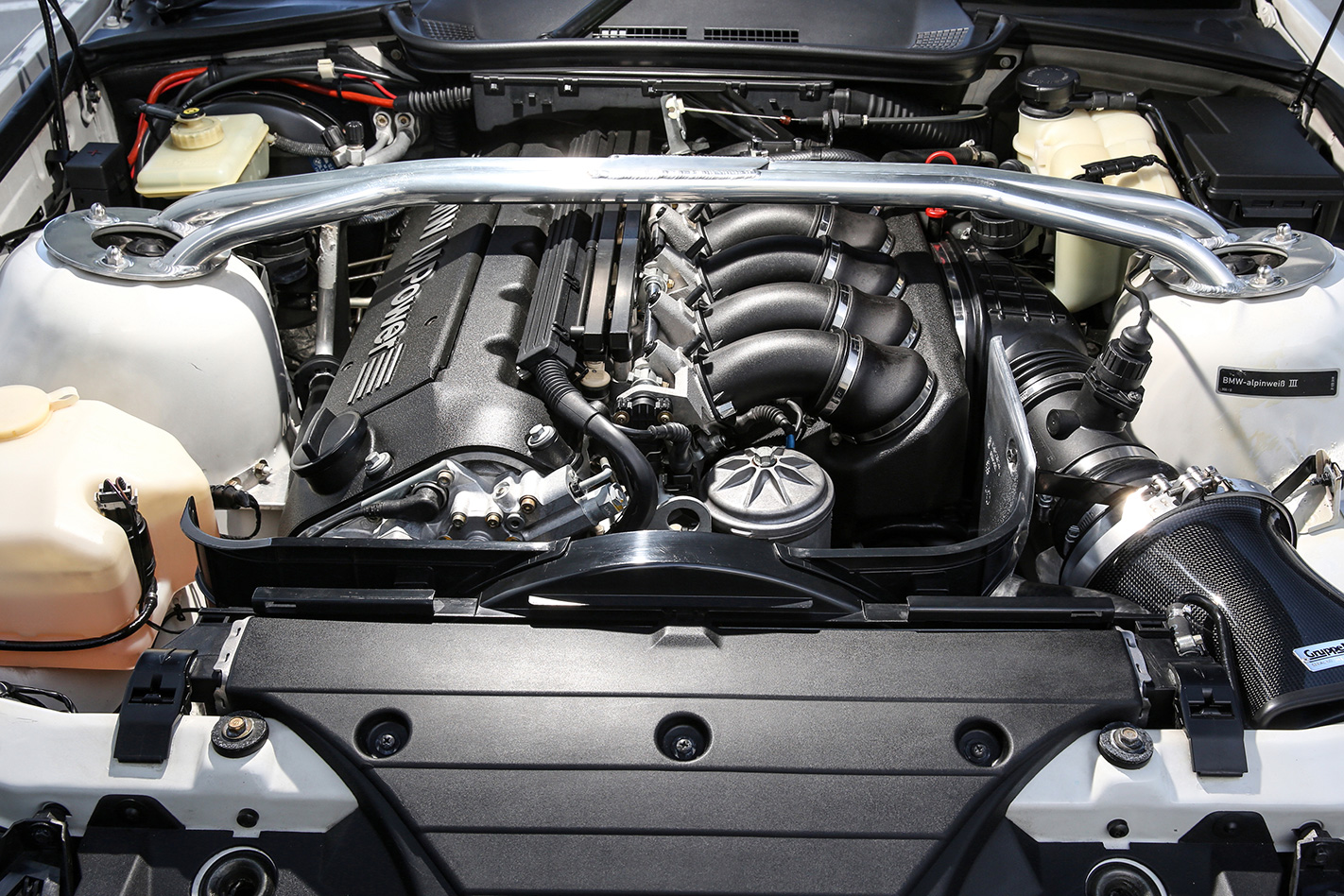

The 2990cc S50 B30 straight six benefitted from new camshafts, a revised intake, optimised exhaust ports, a dual-pickup oil sump and a new ECU to produce 239kW at 7200rpm and 320Nm at 3500rpm. Further down the driveline there was a lightened flywheel and the option of two different clutches depending on whether the car was intended for race or road use.

Research indicates the car also used stronger 850Ci driveshafts and a shorter 3.23:1 final drive, however the maintenance bulletin from BMW Australia, which lists all M3R parts, makes no mention of these. We suspect the latter is likely but the former not.

Standard wheels were 17 x 7.5-inch front and 17 x 8.5-inch rear, but apparently all cars were fitted with optional 17 x 8.0-inch fronts.

BMW M3/M4 Pure announced from $129,900

The M3R wore a $189,450 price tag, a whopping $64,800 more than the regular M3 Coupe. It wasn’t any faster either, stopping the clocks at 5.74sec (0-100km/h) and 14.02sec (0-400m) versus the regular car’s 5.69sec and 13.96sec.

In a comparo against its Mazda and Porsche rivals the verdict was that the BMW was neither fish nor fowl, compromised compared to the standard car yet not fast enough to compensate.

There are still just five ratios, but the E30’s long throw has been replaced by a much tighter gate, and the standard racing clutch has thankfully been replaced by a more progressive item.

Like the E30 the M3R feels to sit squarely on all four tyres and quickly inspires confidence, though the steering lacks feedback and the overly-large wheel dulls initial response.