It’s official: Wheels is 65 years old. But this series isn’t about us. To celebrate our 65th, we thought we’d take a look at the decisions that have changed the automotive world over the last six and a half decades. Some were inspirations that altered it for the better, others were engineering dead ends, nefarious cover-ups and valiant flops. Scroll on to read more, then click here to explore all 65 cars, people, game-changers and failures that have influenced the car industry since 1953, in no particular order.

1. Autonomous driving

The most divisive innovation of the past decade? That’d probably be the rise of autonomous vehicle tech. Keeping the least interested drivers away from a steering wheel and pedal set seems a good idea to us, leaving control of a vehicle to people who are invested in the act of driving. As we’ve seen though, mixing artificial intelligence with the vagaries of human decision-making can be tricky, so squaring that circle will lead to an interesting few years and vast technical challenges. The safety benefits, reduction in congestion and productivity gains inherent in automated vehicles present key points of differentiation to car manufacturers that appear too lucrative to overlook.

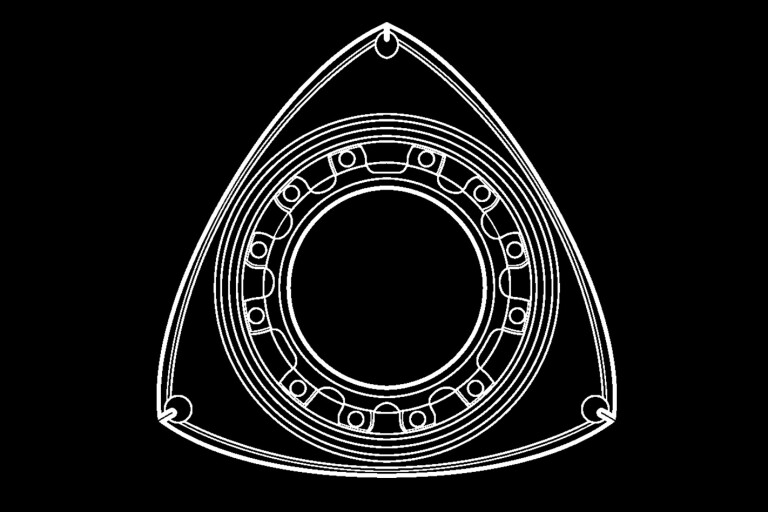

2. Rotary engine

Revolutionary would be too bad a pun for this one, but the Wankel engine design that we know of today wasn’t actually designed by Felix Wankel. The simplified competitor design to Wankel’s rotary was Hanns Dieter Paschke’s work and old Felix hated it, claiming that Paschke had turned his “race horse into a plough mare”. Between 1964 and 2012, the rotary was synonymous with first NSU and then Mazda, but poor reliability, fuel thirst and correspondingly high emissions saw the rotary shelved. The return of the rotary as an EV range extender is being explored by Mazda. Watch this space.

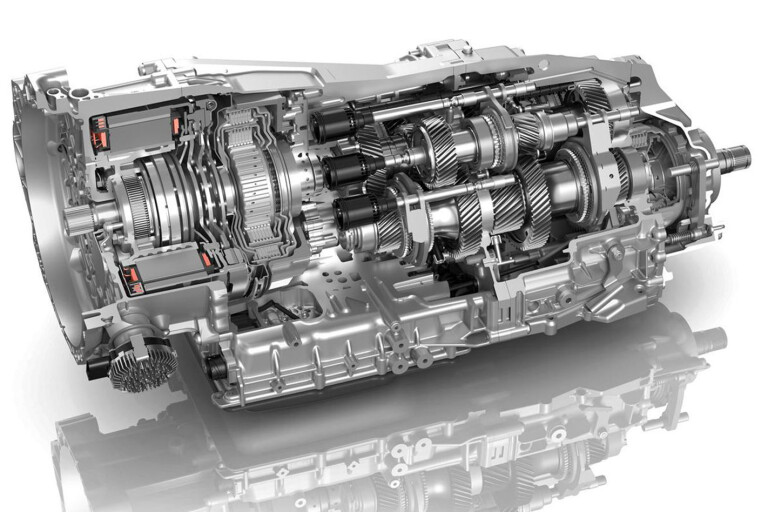

3. Dual-clutch gearboxes

Think of the dual-clutch transmission as a transitive technology. Porsche’s first PDK transmission was seen on the 956 and 962 racers from 1983, later morphing into the Audi Quattro S1 rally car’s gearbox. By 2003, the dual-clutch had been productionised in the Mk4 Golf R32 and seemed a game changer. But durability issues surfaced, and manufacturers of torque converter automatics massively upped their game. The dual-clutch still persists, but it’s possible it’ll go the way of the Wankel. The market will be the final arbiter on that one.

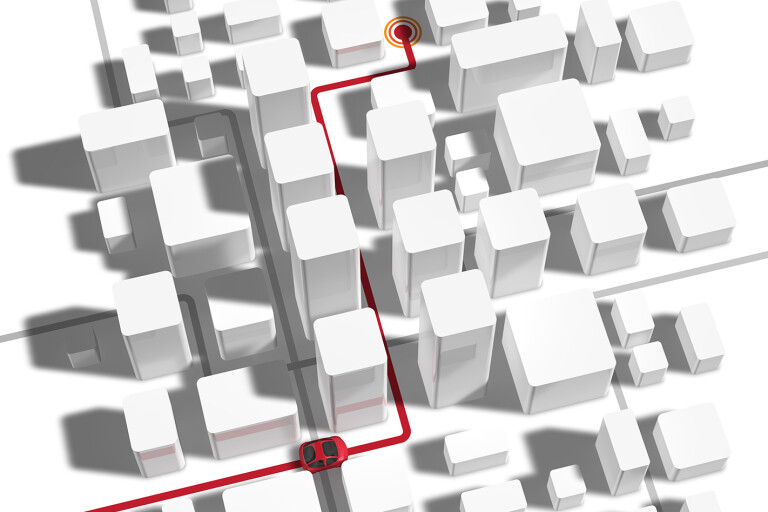

4. Satellite navigation

First car with factory sat nav? That’d be the 1990 Mazda Eunos Cosmo. Prior to that there had been some half-baked systems like Honda’s Electro Gyro-Cator, but GPS changed everything. Or rather Bill Clinton did when he signed a bill in 2000 ordering the military to stop degrading satellite signals, in the process improving accuracy by a factor of 10. Today it’s hard to imagine going back to paper maps, or just pretending to know where you’re going.

5. Ride sharing

Ask any current automotive CEO and they’ll have no hesitation identifying the biggest threat to their bottom line. It sounds simple but it’s people no longer wanting a car. The rise of slick ride- hailing services like Uber has contributed to the fall in driving licence acquisition by late teens. On-demand subscription services also threaten the traditional notion of the two-car household, further eroding the potential customer base. Throw the rise of the autonomous car into that mix and you have a hugely disruptive influence on the traditional car company’s business model. Innovation breeds innovation, though, and car companies are now being forced to respond in kind.

6. Turbo evolution

Remember when the fitment of a turbo was all about raw, unmitigated testosterone? That’s no longer the case. While we recall with dewy eyes the early days of the properly scary boosted motor in vehicles like the Renault 5 Turbo II, the Porsche 930 Turbo and the Ferrari F40, these days turbochargers are more often used to help bolster a downsized engine with low-down torque and for efficiency gains. Turbo lag might be a thing of the past, but so increasingly is the great-sounding normally aspirated engine. Reduced emissions remain the big draw for manufacturers but big forced-induction power/torque numbers keep us excited.

7. Emissions control

Thank Ronald Reagan for kick-starting the modern emissions control movement when he founded the Californian Air Resource Board in 1967. Prior to that, some steps had been taken to curbing tailpipe emissions, including the widespread adoption of positive crankcase ventilation. Sealed fuel systems that couldn’t vent to the atmosphere came in the early ’70s followed by exhaust gas recirculation, and the development of secondary air injection and, crucially, catalytic converters. Between the introduction of Euro 3 emissions rules in 2000 and Euro 5 in 2014, NOx emissions have been reduced more than sevenfold. In theory.

8. Hybrid/electric cars

If we’d never thought of carting a huge vat of inflammable liquid around with us a century or so ago, the notion of doing so now would probably seem vaguely ridiculous. Electricity seems a natural choice for propelling a car, offering near silent drive, no tailpipe emissions, mechanical simplicity and stacks of easy torque. The California Air Resources Board began a big push towards zero-emission vehicles in the early ’90s, eventually seeing Tesla surge to the fore. And yet there’s really only one volume-selling mass-market electric car available, the Nissan Leaf, which passed 300,000 global sales in 2018. And electric cars currently make up 0.0004 percent of Australian car sales. It’s likely to be legislation, rather than buyer behaviour that changes this.

9. Joint development

We tend to think of platform sharing as new, but Citroen spun the Ami8, Dyane, Acadiane, FAFA, Méhari and Bijou from the original 1948-vintage 2CV platform. General Motors shared their Y-body platform across multiple brands in 1960, with Buick, Oldsmobile and Pontiac all top-hatting their designs onto a common chassis. More recently, the VW Group’s $60bn investment in MQB sees a return to the original principles of mass production, cutting complexity and reducing the time taken to build a car by 30 percent.

10. Electronic fuel injection

An engine has to work under a huge range of different conditions and it was soon clear that neither carburettors nor mechanical fuel injection was an optimal solution. Step forward Bendix and its 1957 Electrojector. Step back again, because it was dreadful. It took Bosch to pick up those reins with its transistor-based D-Jetronic system in 1967 to start to realise the benefits of improved power, efficiency and tractability, as well as reducing maintenance and emissions. Most of the major European car manufacturers soon adopted Bosch’s system, with the hugely successful K-Jetronic architecture dominant from 1973 to 1994. Bosch would later mug an ailing Fiat for its rights to common-rail fuel injection.

COMMENTS