Arriving at 'The Wing' at Silverstone on a cold and windy afternoon in early Spring is like turning your internal colour saturation control down to zero. The old World War II bomber base airfield is forbidding at the best of times, but today under scudding nimbus there's one heck of a monochrome welcome. An arrowhead of Mercedes’ most iconic silver arrows race cars sits at the entrance to the function centre.

Mercedes is rolling out the red carpet to celebrate 125 years of motorsport, that anniversary defined by the 1894 Paris-Rouen race. Let’s pause for a little perspective here. Porsche is a newbie by comparison, its racing history commencing in 1951. Ferrari started competing in 1929, by which time Mercedes already had a 35 year competition pedigree. Of the 102 entrants in that race, Peugeot is the only other name that survives today.

To celebrate the anniversary, the Germans had invited the great, the good and its rapid forces division of historic competition cars to the home of F1. As well as a jaw-dropping collection of static displays, just take a look at the driver list. It’s ridiculous. What’s more, they weren’t just there to catch up on old times. A long line of historic cars were available to casually hop into while one of the drivers attempted to give the mechanics something to fix after a lap on either the National circuit or the Stowe loop. At first I was a little crestfallen that I wouldn’t be allowed to drive any of these priceless treasures, but having seen what’s involved to even start some of them, that feeling was soon overcome. Except perhaps for the ten modern F1 cars.

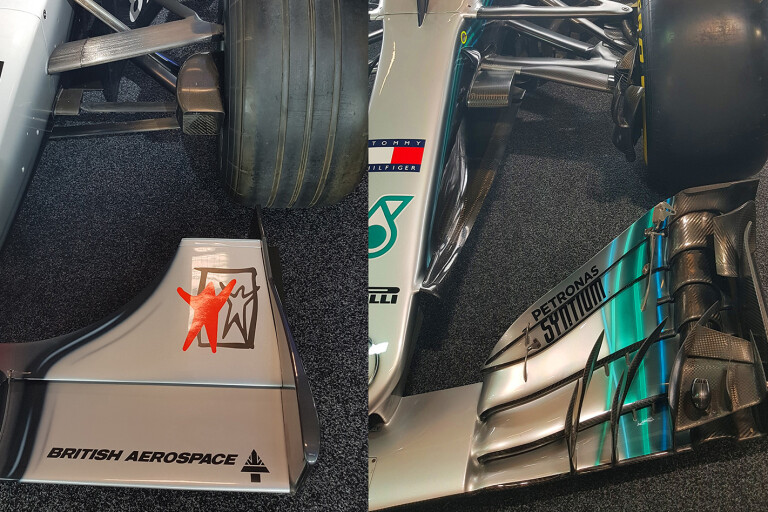

It’s these cars that grab your attention when you walk into The Wing. There’s an unbroken rank of Silver Arrows and it’s fascinating to see the development of the cars each year, from the matte-painted ex-Brawn car that is the 2010 MGP W01 (these snappy names that sound like inkjet printers are an F1 thing, unfortunately) to the current 2019 model. Nestled in among them is the 2012 car in which Michael Schumacher raced his last F1 season.

It’s fascinating to walk along the row, watching the front wings grow more convoluted, the side pods more complex, the front suspension more intricate and the flat floors ever wider. Comparing Mika Häkkinen’s V10 car from 1998 with the 2018 car of Lewis Hamilton is an almost Darwinian exercise in accelerated evolution.

On the other side of the room is an astonishing walk through time from the 1909 Blitzen Benz, fellow Wheels scribe John Carey poring over its antediluvian ignition system. This monster featured a 21.5-litre inline-four and only two of these behemoths now exist. When the car is fired up, the pulses of air being thrashed out of each five-litre cylinder set your diaphragm beating in time. I can only think it must have been the refinement benchmark for the TE Gemini diesel.

Parked next to the Blitzen is the W 125 Streamliner, which set a flying kilometre record on an autobahn in 1938 of 432.7km/h, a mark which went unbroken for almost 80 years until Koenigsegg squeaked past it in 2017 with an Agera RS with almost double the horsepower. Quite amazingly, this pre-war racer had a drag coefficient of 0.17, a good deal better than any modern production car. The current best effort stands at a Cd of 0.22 for Mercedes’ A-Class sedan.

Glance across the room and there’s Lewis Hamilton peering into the cockpit of the Sauber C9 that won Le Mans in 1989. There’s a Bathurst-winning SLS and the Nurburgring 24hr-winning AMG GT, not to mention the CLK GTR, AMG’s first racer, the famous 6.8 SEL ‘Red Pig’, Bernd Schneider gazing wistfully at his DTM-winning CLK.

One of the most remarkable cars here is, curiously, drawing comparatively little attention. The Marlboro-liveried Penske-Mercedes PC 23 IndyCar that featured the radical Mercedes 500I engine is one of motorsport’s great case studies in innovation. ‘The Beast’ won the 1994 Indianapolis 500 by taking advantage of a loophole in the rules that allowed greater capacity and more boost pressure for low-tech two-valve-per-cylinder pushrod engines. In effect it was to allow teams without vast budgets to compete with cheap ‘stock blocks’. Ilmor Engineering didn’t see it quite that way and developed a 1000hp engine for Mercedes that was 200hp more powerful than any other in the field. Al Unser Jr’s winning car had lapped every competitor other than F1 world champion Jacques Villeneuve by the time the chequered flag appeared. Before the car had even returned to its team HQ in Bloomfield, Michigan, the rules had been changed.

Hamilton isn’t just here for the beer either. He managed to get into an entirely unscheduled race with team boss Toto Wolff, an ex-racer and handy steerer himself, when the two of them had commandeered a pair of 190E 2.5-16 Evo IIs. I know for a fact that Toto had bagged the faster car, although I’m not sure who crossed the line first.

Valtteri Bottas is due to wing in today, the announcer in the building giving us the cue to head out onto the balcony to watch him come past on track and to contract hypothermia. He does a couple of fast laps and then decides that he hates his rear tyres and needs to kill them. A demented doughnutting session then commences, but let’s just say that the Finn wouldn’t be taking home any prizes at Summernats. His circle work needs finessing.

After the smoke clears, we head out in some old stuff on the Stowe circuit. Perma-grimacing Roland Asch pedals us round in a 1904 Mercedes-Simplex. Then I jump in with Bernd Schneider in the 1928 SSK. With its screaming supercharger and 165kW 7.0-litre inline six, it’s a riot. Schneider, who has zero mechanical sympathy, drives the car as if he’s on a quali lap, oversteering it into hairpins and using engine braking instead of the woeful anchors.

From there it goes into fantasy stuff, ex-V8 Supercars pilot Maro Engel driving a few laps in a 1955 300SL Gullwing. Engel’s a lovely bloke, but he’s very respectful of the Gullwing out on the Stowe circuit. I’d just seen Bottas drifting the thing, so I’m a bit crestfallen.

Recompense comes in a lap with Ellen Lohr. You probably haven’t heard of Ellen Lohr. I’m projecting somewhat here, because I hadn’t heard of Ellen Lohr. She did a great job compering the gala dinner the night before, but other than that I’m in the dark. It turns out that she’s the only woman to have ever won a DTM round, beating the likes of Bernd ’Mr DTM’ Schneider and ‘King’ Klaus Ludwig in the process. She looks like your mum. I’m projecting a bit here too, because she looks like my mum, but she’s acquainting herself behind the wheel of a 1980 500SL rally car and beckons me to jump in. This model never actually turned a wheel in anger as a works car. It was destined for the 1981 season, with Walter Röhrl leading the team, but Mercedes discontinued its rally activities prior to the season commencing. Shame.

Lohr seems to want to punish the thing as a result. We're sideways before the thing has even left the gates of the car park and delivers the most fun lap of the day. There’s something quite hilarious about seeing this bespectacled lady bang the car into second, give it a giant bung and then send 220kW to the balloon-like and rapidly vaporising Fulda Roteco tyres.

From there, it’s time to suit up and head out with some of the faster cars. At this point, it would be germane to point out that I’m a tallish chap, so most race suits tend not to fit all that well. Or, as in this instance, at all. Imagine trying to don a one-piece garment that’s, crucially, about 10cm too short in the distance between your shoulders and your scrotum and you get some idea of the discomfort involved. Still, some sort of herniated testicle seemed worth a ride in the AMG GT4 car out on the circuit. I put one foot into the passenger seat and then try to fold myself through the aperture in the roll cage. The enormous Stilo helmet clonks in, at which point the HANS device hooks onto the top bar and that was it. I was lodged firm. Only after a lot of hapless squeaking and wriggling do I extricate myself. Check Alex Inwood’s article in last month’s issue if you’re really keen to know what it’s like inside one of these things.

I have better luck in the AMG GT3 car with Engel, which is a good deal faster. It peaks at 237km/h on the back straight before Maro jumps on the picks. That’s significantly better than the 200km/h Esteban Gutiérrez manages in the fantastic 190E 2.5-16 Evo II that Lewis Hamilton had been driving the previous day, but both pale next to the 248km/h that Gary Paffett ekes out of the slinky 2018 C63 DTM car. With a 4.0-litre V8 good for 360kW, the C63 is - modern F1 projectiles included - the loudest thing lapping the track and, after seeing Paffett go a bit Burke and Wills on his initial out lap, I want to give the car the once over to see whether any pieces crucial to staying dirty side down have taken their leave.

All looks agreeably intact, so I strap in, forget for a moment about my abject discomfort and give the 2005 DTM champ the thumbs up. The vibration throughout the cabin when the V8 comes on the cam is incredible, blurring your vision slightly and making every nerve ending in your body feel as it’s been electrocuted. Paffett manhandles the car over every kerb he can find, leaping it back onto the line, jabbing great stabs of lock at the wheel and hitting 248km/h on the back straight. The C63 is a crowd pleaser, drawing a gallery of onlookers every time it fires up and yet Mercedes doesn’t see a future, for the time being at least, in DTM. This car is the last of the line.

Mercedes chose to bow out of this competition at the very top and looking at both the serried ranks of silver F1 cars and the current season results, you have to wonder how much left they have to prove in motorsport’s premier category. It’s an amazing show of power projection and it has me mentally calculating how old I’d be when the marque celebrates its 150th anniversary in motorsport. Too old, I reasoned, so it’s best to just try to soak in the event. I sit in the darkening pit boxes, trying to process what’s been an intense day. An old chap shuffles up and sits with me on the flight cases.

We share a moment, looking over the W196 R Formula One car from 1955. “Ist schön, ja?” I try in 12th-grade German. He smiles, figures I’m fluent and breaks into an uninterrupted five-minute burble. I slowly figure out that I’m talking to Hans Herrmann, the 91-year old who drove for Mercedes in the same era as Fangio and Moss, later winning the 1970 Le Mans alongside Dickie Attwood in a Porsche 917. He’s telling me about his drive in this car in the 1955 Argentine Grand Prix. Valtteri Bottas quietly joins us, grinning and letting the old boy talk. Eventually even Herrmann runs out of words and just gesticulates at the cars in the garage, raising his eyebrows. It seems I’m not the only one who’s slightly overwhelmed.

COMMENTS