It has stood these last 35 years, an eminence grise among all those interested in how fast a car can lap a circuit. Six minutes and eleven seconds: for three and half decades it has been the measure, an expression not only of the concept of speed, but skill, technology and courage, distilled down into a concentrate and expressed in number form. It is, of course, the lap record set by Stefan Bellof in a Porsche 956 at the Nurburgring in the 1983 1000km race, the last time top-level sports car racing competed at the world’s most revered and feared track.

Except it’s not the lap record. And not just because of the extraordinary goings on I was privileged to witness on June 29th this year, but because it never was. Bellof did lap the track in 6:11.1, but only in qualifying. In the race, without qualifying boost and tyres, the best he could manage was 6:25.9, and as lap records are always taken from the race, that is where the real mark has always lain.

And to some there it remains to this day: whatever double Le Mans and five-time Nurburgring 24hr winner Timo Bernhard and Porsche achieved with their 919 Evo that day in June, it represents the fastest ever lap of the Nurburgring’s Nordschleife 20.8km northern loop, not the lap record.

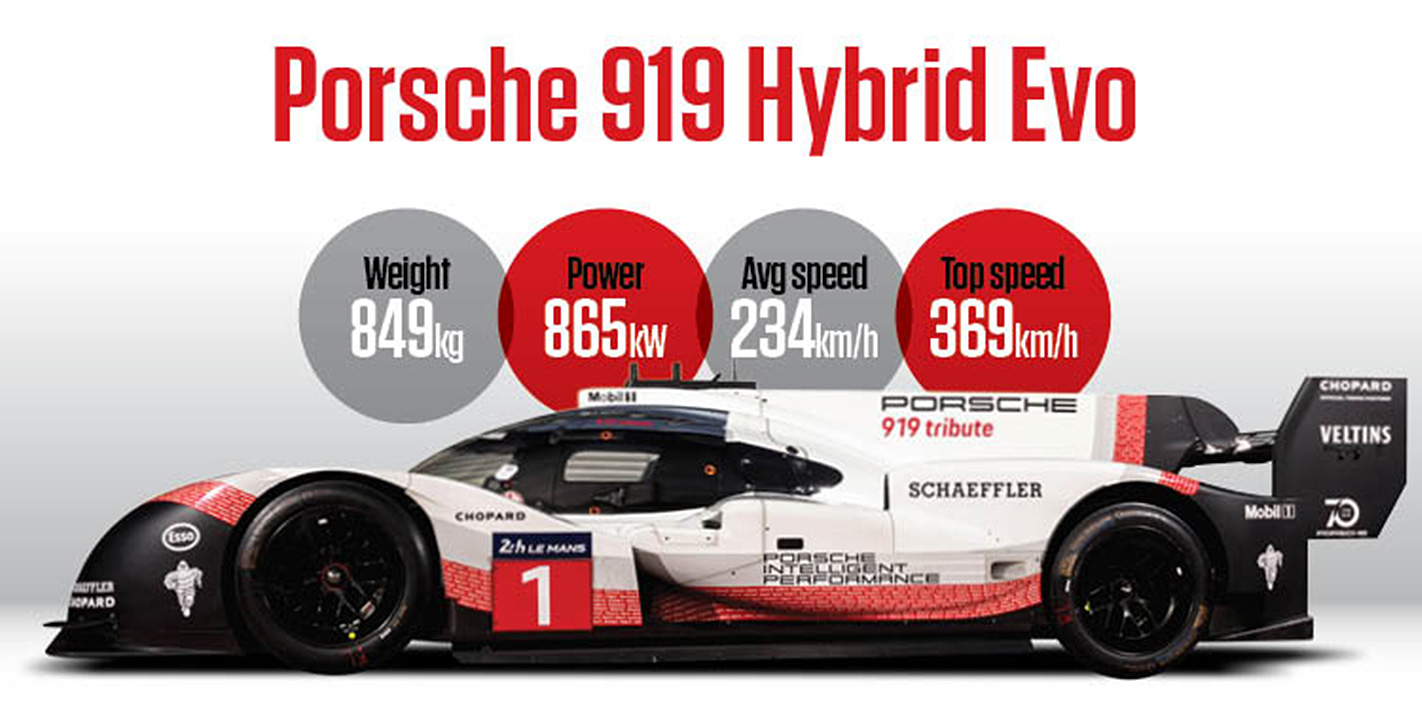

Of course, there have also been the naysayers who point out that the 919 Evo may be a racing car, but not one that can race because it has been developed from the 919 Le Mans car with no regard for any regulations. Its 2.0-litre engine has been uncorked via an unrestricted fuel flow that allows it to produce 535kW. And with an increase in the amount of energy the car can recover, the electrical output was raised by 30kW to 330kW. Most significantly, however, it can not only run any wing pack Porsche likes, but also incorporate full active aerodynamics so straight-line drag can be decimated too. This is how the Evo gets to deploy half as much downforce again as that boasted by the 919 WEC car, yet still goes quicker down the Nurburgring’s main straight than its sister ever went at Le Mans.

Okay, so the car is not eligible to compete in any category. But someone still has to get in and drive it around one of the world’s most dangerous sporting facilities at an average speed most people will not even have driven at, even briefly, just in a straight line.

Yet perhaps most impressive is the way Porsche chose to go about this challenge. Usually when a car manufacturer wishes to set a Nurburgring time, it is done in complete secrecy so that if anything goes wrong or the car is just not quick enough, no-one need ever know of the failure. But for its attempt to break the Nurburgring lap record Porsche has invited a handful of journalists from around the world to witness the attempt first-hand. Win or lose, stand or fall, there will be no hiding from it.

The night before we gather and have dinner with the team. Timo is not only there, he’s happy to chat. I take 15 minutes of his evening during which I ask him how big an achievement breaking the record would be compared to winning Le Mans. Annoyingly he’s so modest and clearly in awe of what Bellof did he’s keen only to point out that what he is about to do is far easier than what his late countryman did all those years ago.

So I ask him how hard he is going to push. A few weeks earlier team-mate Neel Jani had done a lap of Spa 0.8sec quicker than Lewis Hamilton’s pole time from last year’s Belgian Grand Prix which was fairly astonishing but … “at Spa we knew what the target was and how hard Neel needed to push to break it. It was absolutely on the edge everywhere. Here you cannot drive like that: the kerbs are too high and if you make a mistake, well, in a car as quick as this, you can’t really afford to make a mistake…”

And there is some comfort in that: everyone knows that with the firepower at Bernhard’s disposal, breaking Bellof’s time will be easy. Thereafter the only question is by how much. He can take reasonable precautions and still come away with the job done.

Even so there is still a rather sobering moment later in the evening when we are all asked not to broadcast or publish any information in the event of an incident until its true extent can be reliably ascertained. And we all know what is being alluded to here. Even if he doesn’t go at ten tenths, this is a serious and seriously dangerous undertaking and while no-one discusses it, everyone knows it.

The following morning we assemble at the T13 gate, but Bernhard is nowhere to be seen. I ask team principal Andreas Seidl where he is. “Preparing himself,” he replies.

Up close the 919 Evo looks formidable. It’s quite small but the aerodynamic modifications and the deletion of its redundant headlights make it look like some sightless creature from a dystopian future. This is actually the chassis that retired from the lead at Le Mans last year, with only four hours of the race left to run.

Soon Bernhard appears from the innards of a truck, trim and compact in his 919 Evo overalls, his brow and jaw firmly set. He means business.

The track opens at 8:00am and thereafter every second will count. It’s already warm and getting warmer, and Porsche’s calculations suggest that by 9:30am the track temperature will shift the Michelin qualifying slicks out of their peak operating range. Given that Timo must come in after every lap, change tyres and fiddle with the set-up, time is very short.

He goes out and does an exploratory run. I watch from the Pflanzgarten where he passes me at ridiculous speeds, but he’s not trying at all. The lap is around 6min 40sec, not that much faster than a GT2 RS.

So new slicks go on and he has another go. This time he crosses the line after just 5min 31sec and all our jaws fall to the floor as one. He’s not just beaten the record, he’s smashed it into a billion pieces. I approach Porsche Racing PR chief Holger Eckhardt to congratulate him, but he says, “No, no. He’s still warming up.”

The next run is no warm up. Timo is weaving furiously even in pit lane as he drives the wrong way around the circuit for a kilometre, just so he can get a good run up. He flashes past, disappears off in the Eifel mountains and silence descends.

Seidl stands nervously by the timing screen. This project has been his baby ever since Porsche quit endurance racing at the end of last year, and whatever else the 919 Evo does, he knows what we know: this is the big one.

Timo returns carrying barely believable speed into the last turn and blasts across the line. He’s done a 5min 24sec lap and at last the tension dissipates. It turns out the target was to take a full minute off Bellof’s race record lap. Bernhard climbs out of the car; the job is done.

Or maybe not. A few minutes later he returns, tyres are out of their blankets and he’s being strapped back in. For all his intentions to not push too hard, the racer’s instinct has prevailed. He’s going to put it all on the line. Within a minute he’s gone again.

The wait is agonising, but soon we can hear the ugly blare of the 919’s engine as the car hurtles down the straight. Almost immediately he’s with us, slithering across the kerbs and over the line to record a lap of 5min 19.546sec. The place erupts. There is laughter and there are tears. More than anything there is relief, not just at a mission accomplished in which the team did something no-one else had ever come close to achieving before, but more at the knowledge that car and driver were still in one piece.

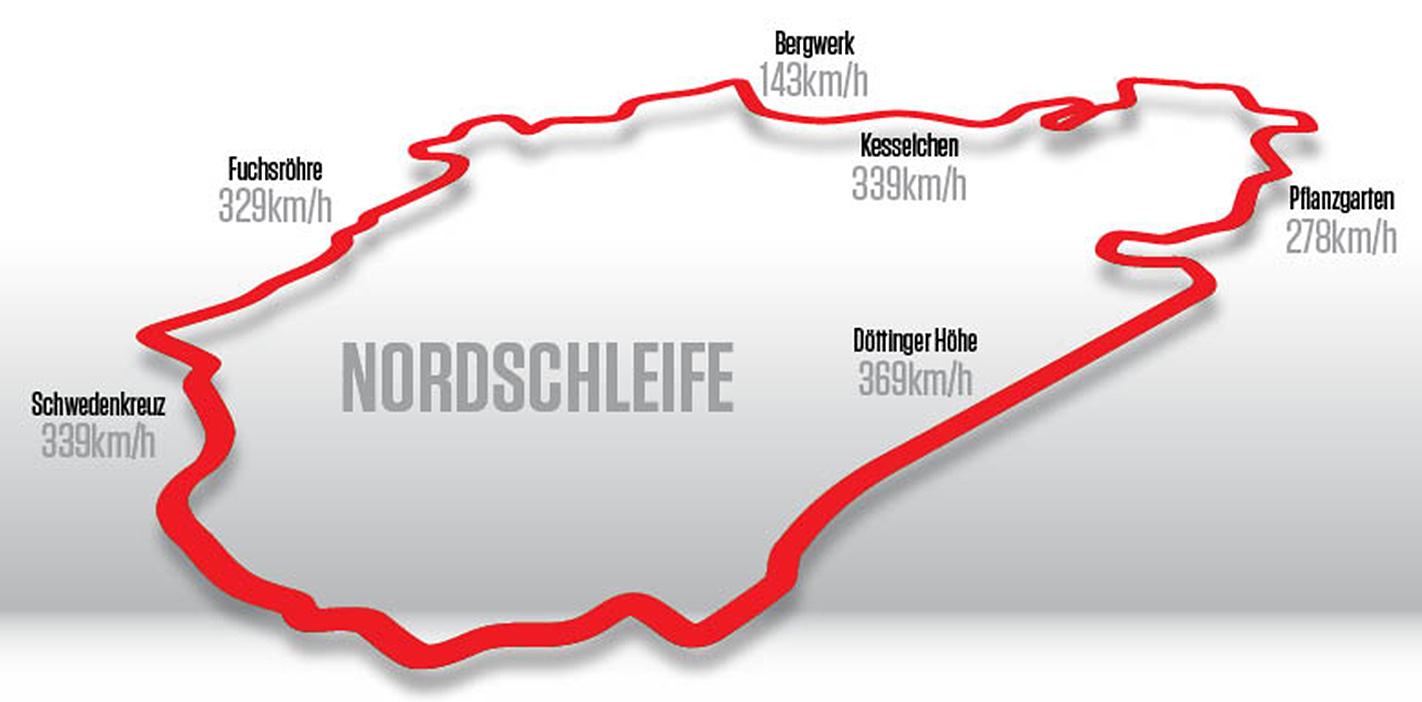

And then the data gets crunched. The car’s average – average – speed over that lap was 233.9km/h. It turned into the crest at Schwedenkreuz at 322km/h, and blasted down the straight at 369km/h.

Perhaps most bewildering of all for those who know their way around this place, Bernhard hit the compression at the bottom of the Foxhole at 328km/h and never even thought of lifting.

I’d like to say now that it will take a little time for me to get my head around such numbers so as better to appreciate what Porsche and Bernhard achieved that day. But the truth is I never will. Fact is, the harder I think about it, the more incredible it becomes. Had I not been there myself I might even have struggled to believe it. But I was, and the memory will be with me for the rest of my days.

It’s interesting to note that, so far as I am aware, the Nordschleife in its fabled configuration was in fact used for just one major motor race – that 1000km event in 1983. All other races, including all the F1 races were held on the combined northern and southern loops.

Black day at Spa

Stefan Bellof was just 27 when his Brun Motorsport Porsche 956 made contact with the works Porsche 962C driven by Jacky Ickx at Spa in 1985.

Bellof, a fearsomely quick and talented driver, was lining up a pass on Ickx through the infamous Eau Rouge kink. The impact was monumental, and the young German didn’t stand a chance. It cut short a potentially brilliant career: Bellof was in talks with Ferrari for an F1 seat for the 1985 season.