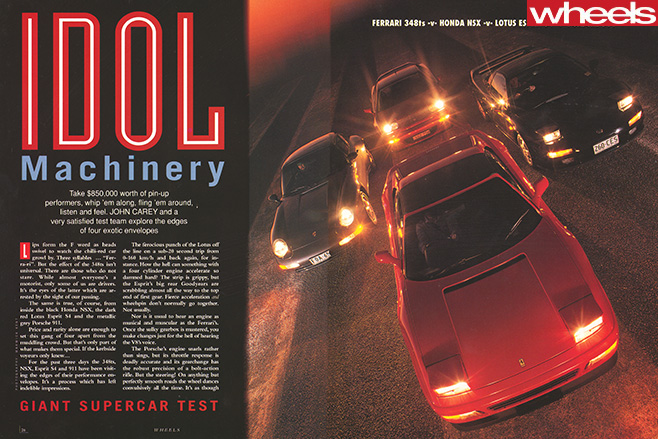

Take $850,000 worth of pin-up performers, whip ‘em along, fling ‘em around, listen and feel. John Carey and a very satisfied test team explore the edges of four exotic envelopes.

First published in the May 1994 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

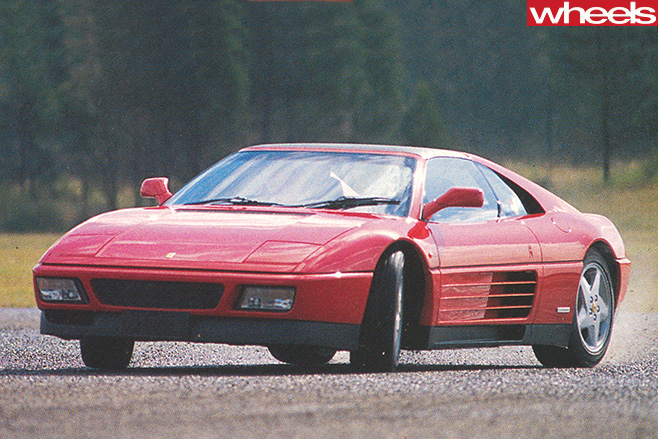

Lips form the F word as heads swivel to watch the chilli-red car growl by. Three syllables… “Fer-ra-ri”. But the effect of the 348ts isn’t universal. There are those who do not stare. While almost everyone’s a motorist, only some of us are drivers. It’s the eyes of the latter which are arrested by the sight of our passing.

The same is true, of course, from inside the black Honda NSX, the dark red Lotus Esprit S4 and the metallic grey Porsche 911.

Price and rarity alone are enough to set this gang of four apart from the muddling crowd. But that’s only part of what makes them special. If the kerbside voyeurs only know…

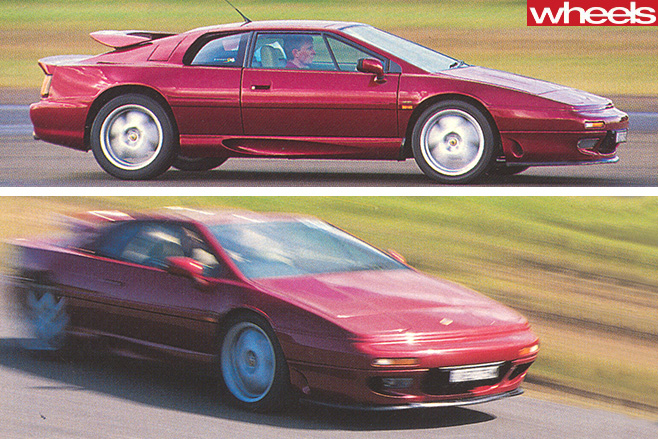

The ferocious punch of the Lotus off the line on a sub-20 second trip from 0-160 km/h and back again, for instance. How the hell can something with a four cylinder engine accelerate so damned hard? The strip is grippy, but the Esprit’s big rear Goodyears are scrabbling almost all the way to the top end of first great. Fierce acceleration and wheelspin don’t usually go together. Not usually.

Nor is it usual to hear an engine as musical and muscular as the Ferrari’s. Once the sulky gearbox is mastered, you make changes just for the hell of hearing the V8’s voice.

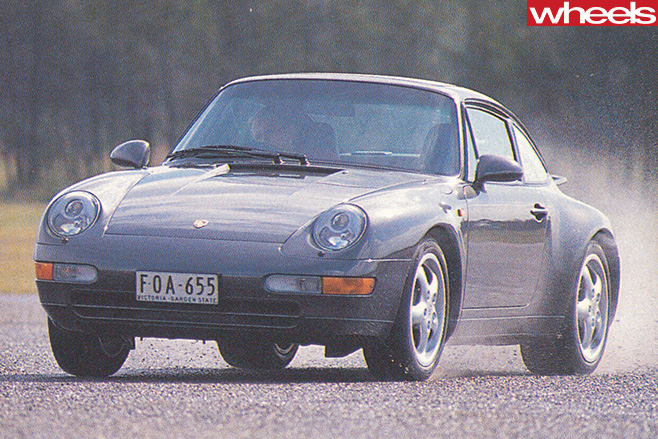

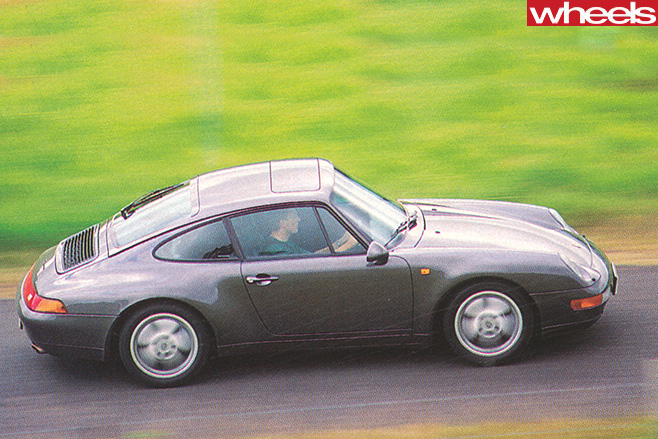

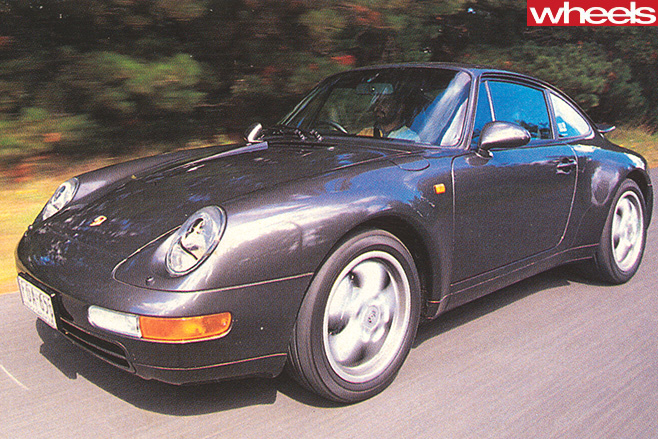

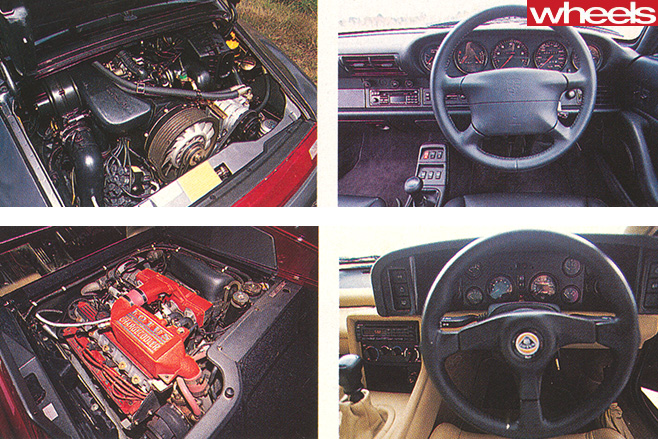

The Porsche’s engine snarls rather than sings, but its throttle response is deadly accurate and its gearchange has the robust precision of a bolt-action rifle. But the steering! On anything but perfectly smooth roads the wheel dances convulsively all the time. It’s as though the steering is eager to tell you about the shape of every fragment of gravel passing beneath the front wheels.

The hallmark of the Honda, on the other hand, is its serenity. Tumbling down a sinuous mountain pass, the Porsche cannot escape the pursuing Honda. The driver of the German car is working hard, tempering exuberance with caution because, in places, the road is damp. The NSX driver, meantime, wonders how Honda’s workers stitch the leather covered dash so perfectly it could be mistaken for a plastic moulding.

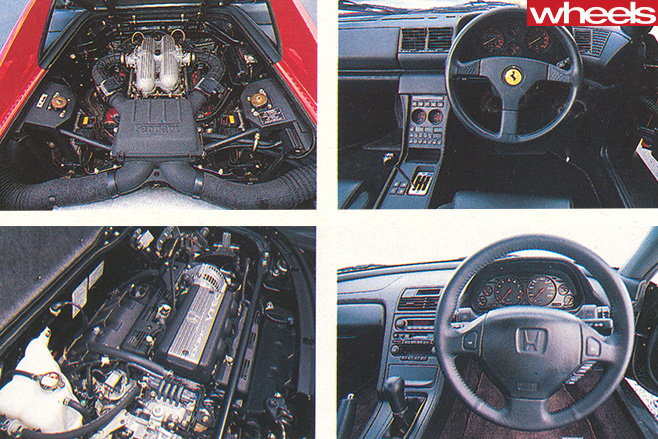

In simple terms of basic layout the Ferrari and Lotus are perhaps the most alike. The Italian and British cars both mount their engines lengthways behind the cabin. Both have double wishbone suspensions at all four corners.

But there are large differences too. The Ferrari 348ts is powered by a naturally aspirated 3.4 litre V8 which can trace its lineage back to the ’70s, the Esprit S4 by a 2.2 litre turbo four of similar age. The Ferrari’s body is the work of lambrusco-sipping metalworkers, that of the Lotus is manufactured by beer-drinking glass fibre fabricators before being married with a steel backbone frame.

Honda’s NSX isn’t burdened by a long, glorious and carefully nurtured pedigree. The designers of this car weren’t impeded by any pre-existing notions of what a Honda-badged supercar should be like. As well, despite the popular prejudice, there’s nothing imitative about the NSX. The company’s adoption of a V 6 engine with a capacity of only 3.0 litres is alone enough to set it apart from the others. And while that engine is mounted midship, it sits crossways in the engine bay. And let’s not forget its all-aluminium body and mostly aluminium suspensions, either.

But among this group of distinctly different cars the Porsche is, technically speaking, the most ruggedly individual of all. Its shape and proportions are rooted in a long-ago era. So, too, is its basic layout. Despite the latest makeover of the 911, the most significant in the car’s long history, it remains an amalgam of 30-year-old decisions. Most importantly of all, the 911’s 3.6 litre horizontally opposed and air-cooled six is in the car’s tail, slung aft of the rear wheels. If Porsche’s engineers were to sit down to design the 911 today, it’s doubtful that they would (a) opt for an air-cooled engine in the first place, (b) put such an engine out of the breeze in the car’s tail, or (c) outside the wheelbase. The 911 is at once a prisoner of its past and a triumph of painstaking development engineering. The car has no right to work so well.

Four quite different cars on the drawing board, four quite distinct driving experiences . . .

It’s only when you allow the engine full voice that the 348’s drivetrain really works. Though the clutch isn’t too heavy, shifting gears is neither easy nor pleasant at low to middling speeds. The chrome lever demands determined application of muscle all the time. Pussy with it and it’s a bulky bastard. The difficulty is magnified by a race car shift pattern which puts second to fifth on a conventional H, with first on a left-and-back dogleg. Further confounding efforts to achieve low speed smoothness is a heavily damped throttle pedal. It requires more than usual foot force and, when released, springs back with deliberate slowness.

It all works – and only works – when the Ferrari is bullied up to speed. Only then does this drivetrain achieve harmony. With the engine singing full-throated, the driver feels as much a conductor as a steerer. At each pause for breath and a gearchange, the lever – now moving fast and fluently between ratios – clickclicks like knitting needles as it slides through the trademark exposed gate. The pure gut appeal is no surprise to anyone who knows why Ferrari has the reputation it does. It’s very much like what you always imagined a Ferrari might be.

And the Ferrari offers perhaps the best deal of all for the passenger. The dash is low and distant, and there’s abundant legroom (unlike the Porsche).

Visibility is good in all directions. If it weren’t for the recalcitrant drivetrain, the Ferrari would be a great supercar for doing the shopping. Like everything except the Lotus, the interior is black on black, relieved only by the garish orange of the markings on the two major and four minor dials and the green status lights of the ventilation system. Oh, and the yellow background for the prancing horse horn button set in the middle of the Momo wheel. Airbag? Domani…

The 348’s ride is very damned hard. If your stomach muscles aren’t firm the 348 will make you fully aware of the fact. Its steering is unassisted and quite heavy It loads up, but it’s not the senseless kind of muscle building that’s the result of second rate front suspension geometry. The changes in weight telegraph vital information about how the front tyres are tracking and how much work they’re doing. The wheel wriggles over other than perfect road surfaces too, though not as energetically as the Porsche.

You might niggle about the firm suspension and weighty steering round town, but there’s no argument it works when attacking a challenging road.

The Ferrari turns in instantly, all of a piece. Its engine response is precise and so is its chassis’ response to the engine. The 348 is a car that rewards smooth and precise driving with ferociously fast, flowing progress.

The Honda’s cockpit fits like a glove… and is about as complicated to use. Everything is exactly where you expect to find it. But the cabin is a close fit, tighter than Porsche and Ferrari.

But the outside of the car is not so evocative. The Honda’s looks are the least exciting of all, by consensus. Are people disappointed when they find out it’s not a Ferrari? Does interest wane when they discover the engine has but six cylinders? Yes and yes.

Huh! What do we care for the opinion of someone who can’t tell a Honda from a Ferrari?

The NSX is a quite different driving experience from the Ferrari; it rides more compliantly than the 348, has deliciously well weighted and feedback-free steering, and is every bit as quick. Its chassis invites familiarity and cultivates confidence more easily than any of the others. Partly it’s the application of technology like the (switchable) electronic traction control, which means you can use full throttle exiting water slicked turns without fear of the consequences. But mainly it’s the sheer, overwhelming competence of the suspension.

The Lotus delivers a quite different impression – that of a master-built kit car. But for sheer off the line savagery the Esprit feels the most ferocious and records the numbers to confirm the impression (see panel).

Spooled up to 5000 revs, the 2.2litre turbocharged and intercooled four sounds wild. Sidestep the clutch and the Tupperware Terror explodes forward. The engine stays in the boost zone, the tyres spin. Such is the bounty of turbo torque that the rear rubber only hooks up to the bitumen right at the top of first gear. By this time you know there’s a feral powerplant just behind your head. The noise is like a butcher’s handsaw as it slices through bone. It’s a shrill, whining, insistent, thrilling noise.

The gearchange is far from satisfactory though. The forward gears move in a conventional pattern, but the feel through the lever is more vague and rubbery than the others. As well, the lever is about 25mm too long for a natural grasp with left elbow resting on the broad central tunnel. Reverse is both unnatural and awkward to engage. It’s left and back, with a collar detente to be lifted to get beyond the first/ second plane.

Visibility is poor enough that driving in traffic is the stuff that nightmares are made of There are sizable blind spots to the three quarter re.ar on both sides. Rearward visibility through the letterbox slot window isn’t good either, and the sail panels sloping down from the B pillars pick up reflections which flash distractingly in the interior mirror.

Only beyond choking city traffic do the British supercar’s strengths become evident. The steering is pretty good, you soon notice. Though the non-adjustable wheel is low set – partially obscuring the two major instruments – weight and feel are nicely judged. At the straight ahead there’s no writhing feedback through the rim of the small diameter leather-bound rim. And you don’t have to chase it all over the place on poorly surfaced roads. It’s better than both Porsche and Ferrari, demanding less attention on backroads in cruise mode. Ride quality falls somewhere between the Ferrari and the Honda.

Cautious in, sure, but no such trauma on the way out. The Lotus hunkers down and drives, though it does understeer more readily than the Ferrari or the Honda. There’s no real turbo lag to speak of, but the delivery differs. It has the typical turbo trait of lacking those last few degrees of precise throttle response.

The Porsche’s engine, though, is the most satisfying of all. The accuracy and immediacy in its answers to the accelerator pedal are really gratifying. No turbo, no VTEC. Just Grade A thrust in direct proportion to right foot pressure.

Besides a honey of an engine, the 911’s other impressive traits are its practicality and unbreakable feel. It’s the car easiest to get into and out of, mainly because it’s older and taller than the others. But once inside that age is apparent in a different way. The markedly offset pedals sprout from the floor. If these guys can do a redesign of the 911’s rear suspension, why, oh why, can’t they do a nice set of pedals? You have to make sure you push the clutch with the top of your foot so your toes don’t hit the lower edge of the dash.

But the cabin is relatively roomy, for its faults. The 911 is the only one to offer any attempt at accommodation in the rear. Though it’s unlikely any adult will ever squeeze in there, the amount of cabin space is uniquely accommodating among this company. Visibility is very good out of the Porsche, too, though it’s a close thing between the German and Italian cars.

In other ways, which count more, the 911 is a mixture of the superb and inexcusable. It has, for example, the only six speed gearbox. It’s the best shifter of these four. But does the steering really need to squirm in your hands the whole time?

Dynamically it marches to a different drummer. Brake during turn-in to keep the nose nailed solidly to the bitumen. Then squeeze on the power for a ticket in the front-end grip lottery on the way out. The Porsche squats on its haunches and thrusts hard, the front tyres go light and very sensitive to changes in surface conditions. Particularly wetness.

This is a car which confronts driver inadequacy head on. In character it’s the most challenging car of this exotic group. And because of this the Porsche makes a driver feel a bigger hero. It might be better behaved than any previous 911, but you still emerge from the experience smiling because you’ve conquered the car’s fierce queerness.

In this respect, the Porsche is the anti-Honda. The driver of the NSX merely co-stars in an act of awesome competence. The NSX, by almost any rational measure, is the best, most perfect, of these cars. And this very excellence limits its appeal.

The NSX will get there every bit as quickly, without the pulse racing and palms sweating. Without feeling you’ve performed an automotive opera with the 348ts, or have whipped a wild 911 into submission, or have pulled the pin from an explosive device called Esprit S4.

Don’t try to explain such satisfaction to people who are mere motorists. They just won’t understand