THE MODERN DRIVER is conditioned to expect that the turn of a key or the push of a button will, through some invisible and unimportant process, start the engine.

Symphony in C was first published in Wheels in June 1987.

Similarly, some preprogrammed wriggling down the left side of his body will cause a clutch somewhere to disengage, and a new gear to be selected. Electronic engine management systems and sensor-studded anti-lock braking devices mean the modem driver, in his hermetically sealed environment, simply goes through the motions of “driving a car”, insulated in his plastic pocket from any activity taking place underneath.

A Jaguar XK120 C-type is in theory a car like any other, yet the time and purpose for which it was built makes it completely different for the modem driver. Clinging to the large steering wheel, eyes smarting both from concentration and from the battering wind, one becomes acutely aware of each individual action and its response. In the C-type, one isn’t just “driving a car”, but using the utmost of precision in conducting an orchestra of free-thinking mechanical components.

And the stench and snarl of the engine washing through bonnet louvres, the graunch of the Moss four-speed ‘box when hurried amateurishly through its gate and the suicide leap taken by the brake pedal when it hasn’t had its reassuring dab, aren’t going to let you forget it.

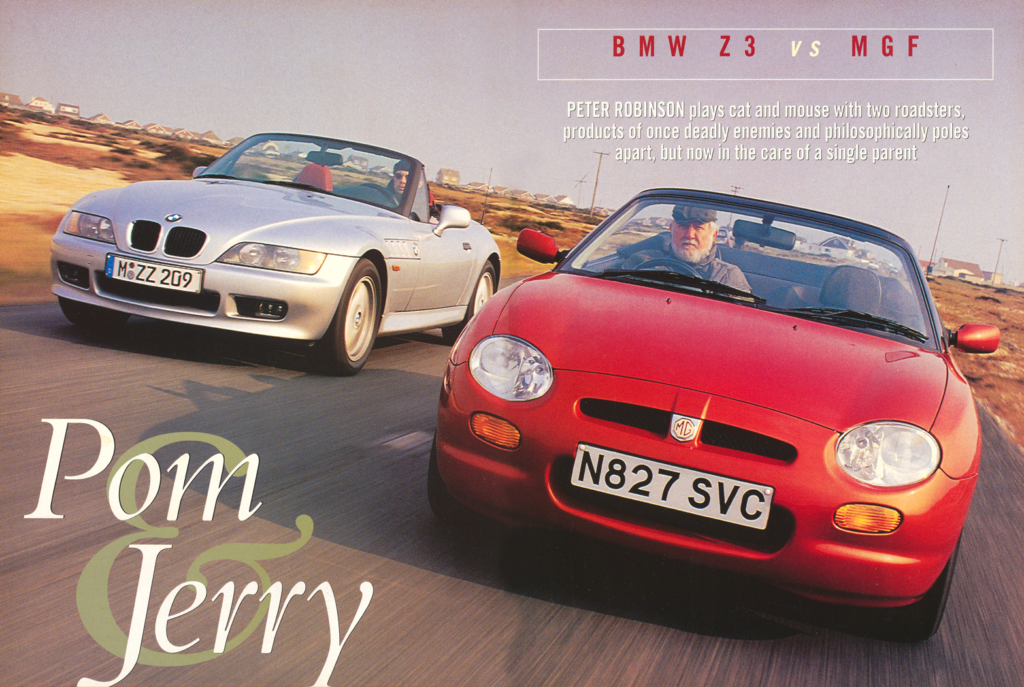

It’s one of automotive history’s typical anomalies that everyone knows an “E-type Jag“, but few are aware of the D-type before it and fewer still of the C-type. Yet the C-type is arguably the most significant of all, for as well as bringing Jaguar its first victory at Le Mans, it was also one of Britain’s pacesetters in spaceframe construction and sports car body aerodynamics.

The modem driver arrives at the workshop home of XKC-021 with visions of steering wheel-mounted spark advancers, friction dampers and Isadora Duncan’s flowing scarf episode swimming in his head. Paul Corner, who rebuilt the mechanicals of the Marshall C-type and was subsequently appointed keeper of the cat, raises his eyebrows and scoffs, “Strewth, what were you expecting – a blower Bentley or something?” The modem driver in reply explains that, to within a fortnight, XKC-021 is exactly 10 years older than he is.

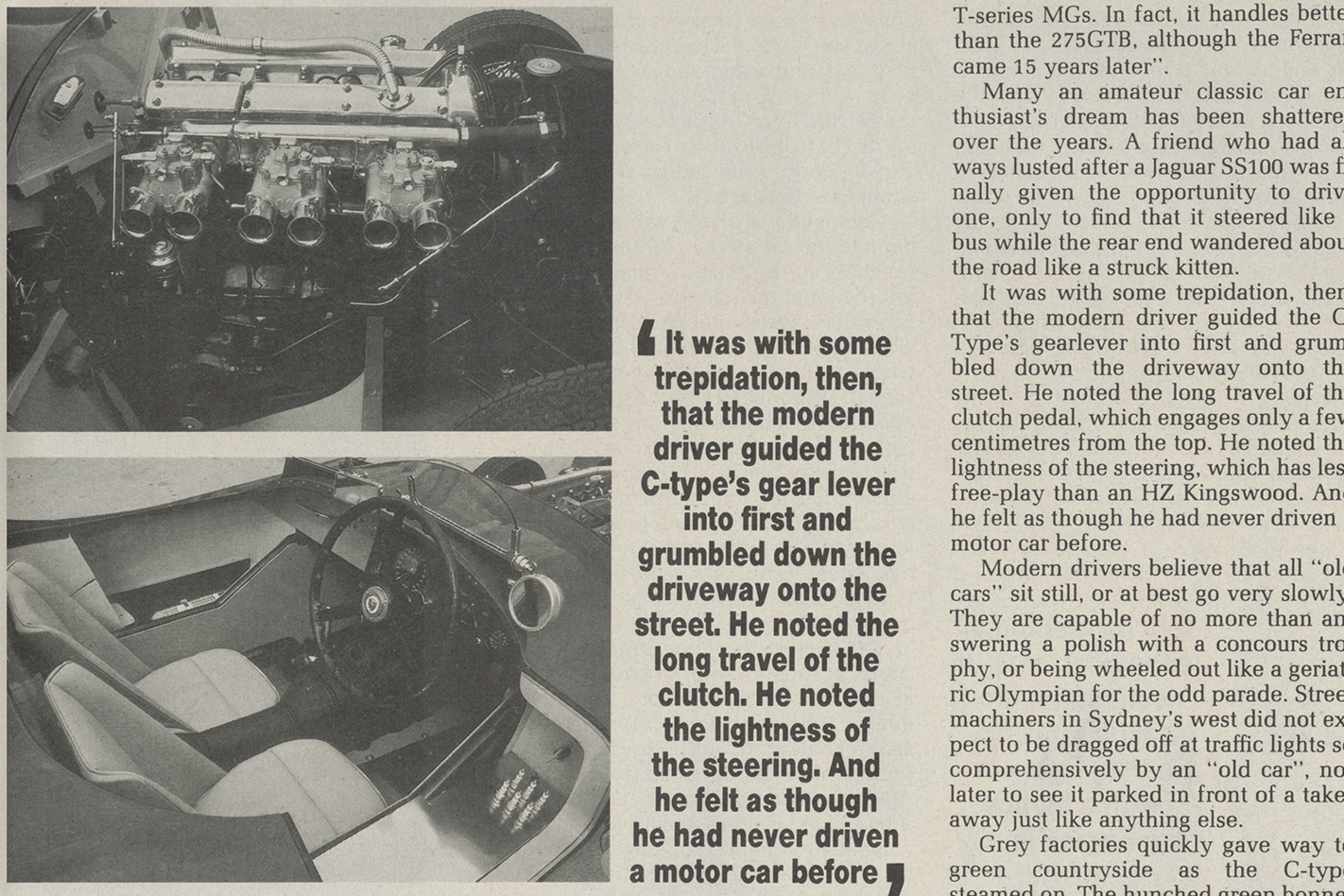

The Jaguar C-type was built to further exploit the motor sport successes of the “touring” XK120, and was designed and developed in a breakneck six months before the 1951 Le Mans race. Construction of the first three works cars had been kept so secret that no one – not even the enthusiastic staff of the fledgling British weekly Autosport – had expected Jaguar to front with anything other than the regular XK120s. Although the C-type was a markedly different animal to the XK120, it had nevertheless been built by hands well-greased in the XK120 parts bin. The 3442cm3, in-line six-cylinder engine retained the familiar-enough twin-ohc layout of the XK120, but with higher-lift camshafts. Two different piston types were available, providing the choice of either an 8:1 or 9:1 compression ratio depending on the fuel to be used.

Other tweaks included a different distributor and different needles in the twin 1 3/4-inch SU carburettors which were the original equipment in 1951. Two years later, Harry Weslake demonstrated that three 45mm Webers upped the power from the original 150kW at 5800rpm to a more useful 163kW at 5250rpm, with particularly useful gains in the mid-range.

The C-type’s spaceframe was a total departure from the XK120’s more traditional ladder-frame construction. Lightness and strength being the primary objectives, four main box-section steel bulkheads are joined by a complex triangulated network of steel tubing to form the “cradle” for the engine and occupants. Along the base of the rearmost bulkhead, against which the two seats rest, is the transverse torsion bar that provides rear springing through trailing links.

Until the time of the 1953 Le Mans, lateral location of the rear axle was handled by a fairly simple “torque reaction member”, a sort of claw that was bolted to the right hand side of the axle. Seems it never really worked too well. Dr William Marshall’s car was retrofitted in 1953 with the improved A-arm and Panhard rod arrangement. Longitudinal torsion bars are used at the front, and Newton telescopic shock absorbers are fitted both front and rear.

Each of the aluminium body panels on XKC-021 is the original factory banana – albeit with some additional handiwork over the past 34 years – and still carry their identifying “K1021” tags.

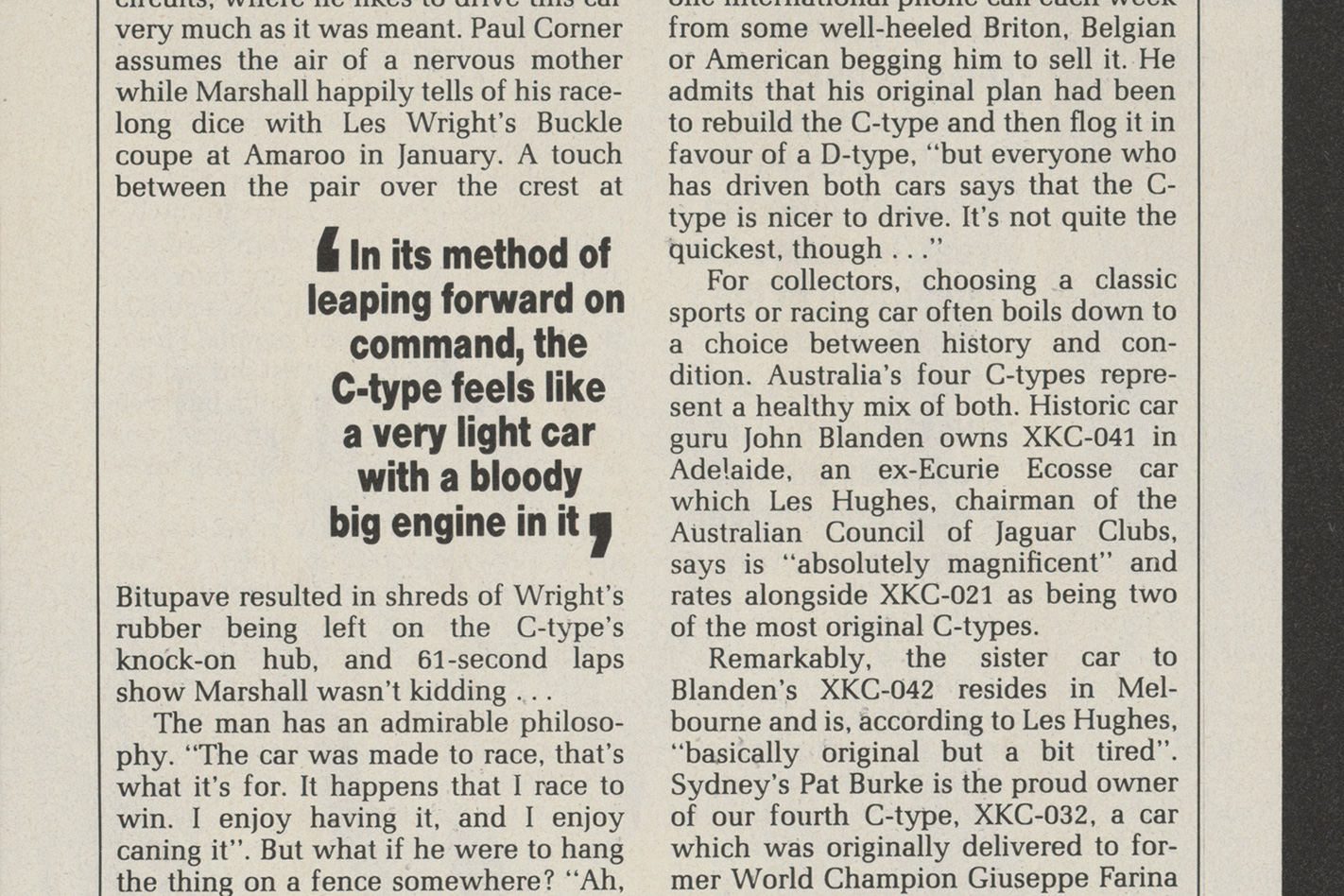

Even the leather strap for the single door is the original item. The combination of spaceframe chassis and an all-aluminium body helps the C-type down to a kerb weight of 1016kg, and that with a claimed weight distribution of a perfect 50/50 front to rear. Once inside the cockpit, its driver and passenger aren’t made to feel like afterthoughts, but its list of “comforts” is still obviously directed to getting on with the job. These include a height- and depth-adjustable steering column, which admittedly takes some fiddling with tools.

For all its history. its purity. its rareness, XKC-021 still needs a piddly little steel key and a starter button to get it going. The engine chums and then cracks into motion. The modern driver is at once pleased and disappointed that the idle is not coarse or lumpy; that the seat doesn’t jiggle up and down like a helicopter’s; that nowhere can be heard rattling panels and flapping bits of metal …

The exhaust note is unique. It pummelled through the twin pipes next to the passenger and raced through the door of Barry Graham Automotive, kicking some drums and rearranging the furniture as it went. It then descended again on the C-type, straddling the cockpit and encrusting itself around the soul of the modern driver.

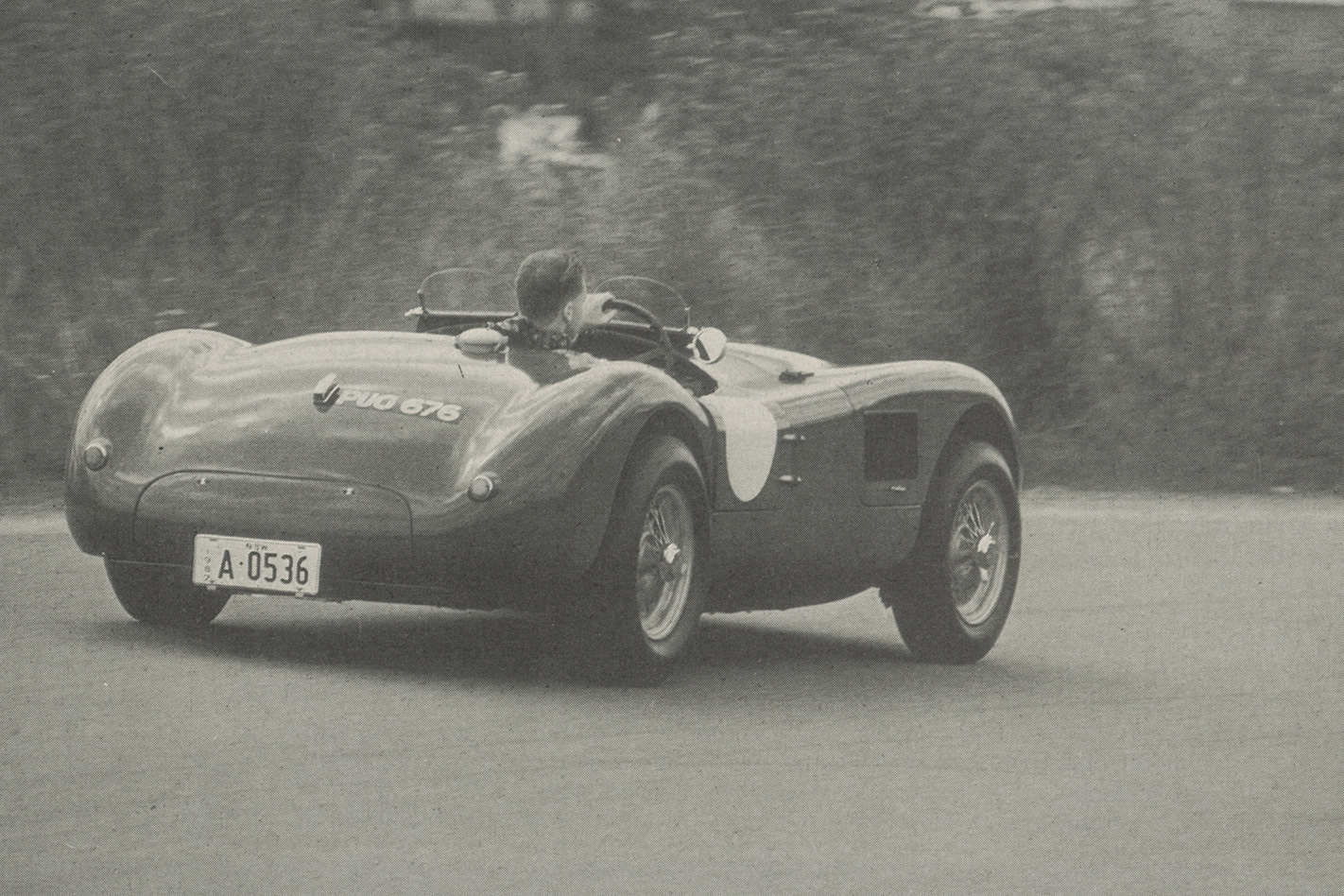

His mind went back. At age six he believed that the Tasman series cars warming up their engines at Warwick Farm were saying “Brabham, Brabham”. A backfire suggested “Jack”, and although The Great One wasn’t yet knighted, a trailing throttle would have been good enough for “Sirrrrr”. Not like a six, yet not like a VB, the C-type’s growl has a complexity of timbres, tannins and the maturity of a classic Beaujolais. And it is saying “drink me, drink me … ” It was the custom of Jaguar’s William Lyons to have his cars driven all the way to Le Mans from the old Swallow Lane factory in Coventry. Thus, engineers Ray “Lofty” England, Jack Emerson and Phil Weaver set out early in June, 1951 in XKC-001, 002 and 003.

Four hours into the race itself, these three cars occupied first, second and third places. Suddenly, the third placed car of Clemente Biondetti I Leslie Johnson lost oil pressure and was out.

Shortly after midnight the leading car of Stirling Moss/Jack Fairman suffered the same fate. The eyes of the Jaguar crew turned to the remaining car of Peter Walker/Peter Whitehead. Investigation showed that a copper pipe within the sump was cracking due to engine vibrations, and in turn starving the bearings of oil, thus outing XKC-001 and 002. The message was relayed to Walker and Whitehead, who held their revs accordingly. Whitehead crossed the line to score a debut win for the C-type, barely six weeks after the car had first turned a wheel.

Jaguar’s fortunes at Le Mans in 1952 were very much the product of this panic. New long-nosed bodywork was fitted in an effort to increase speeds along the Mulsanne straight. To fit the new bodywork, the radiator header tank was moved back to the firewall, but through a quirk of engineering fate this proved to be the Jaguars’ undoing. Each of the works cars overheated and expired early in the race. Deliveries of “customer” C-types, with the koala-face bodywork to which the factory would quickly revert, had commenced just a few weeks before.

The cars, however, were not for sale to just any well-heeled wanker – such people would have to wait for a Corvette or a Shelby Cobra. Instead, Jaguar preferred to dole out the cars to those with prior affinities to the company.

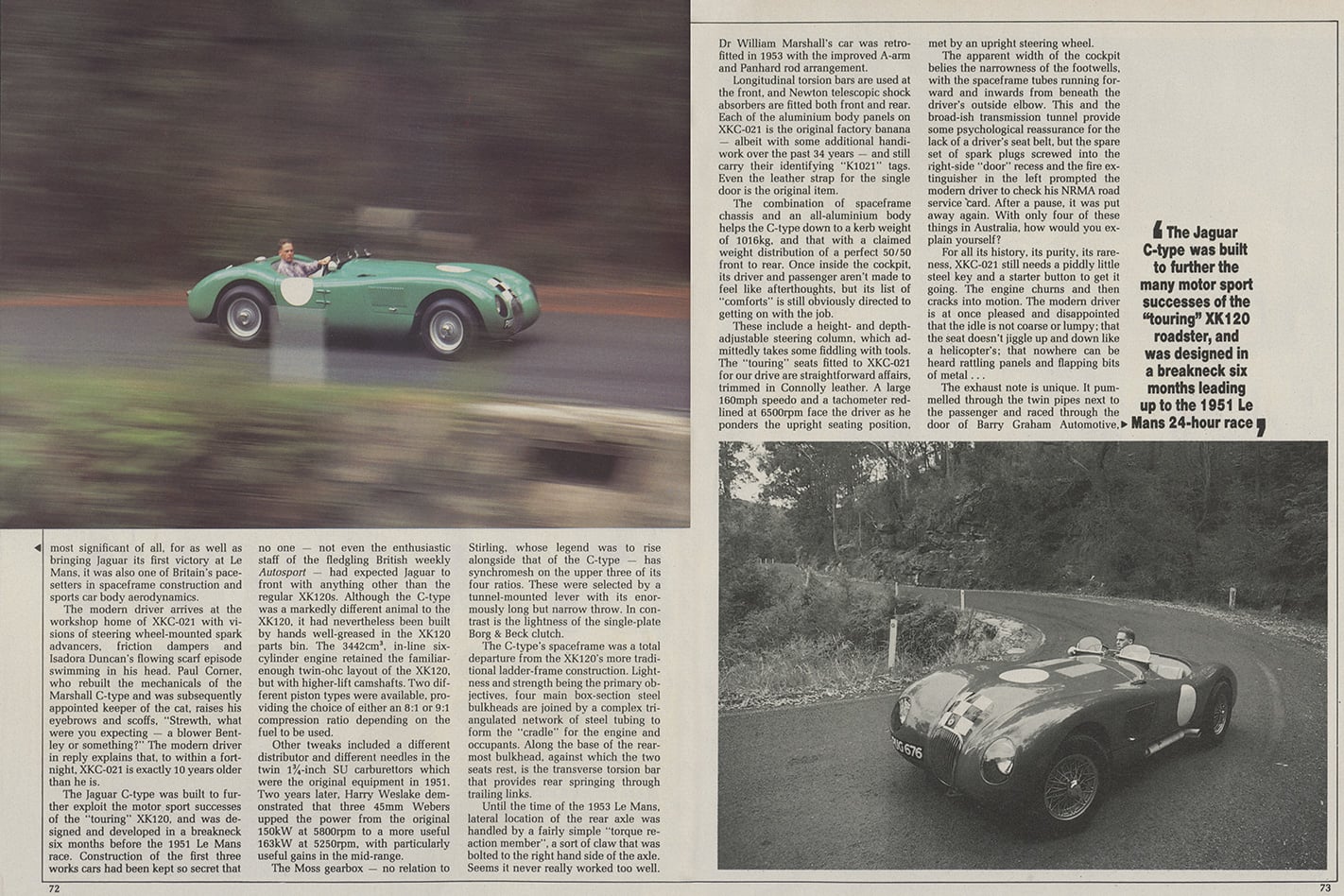

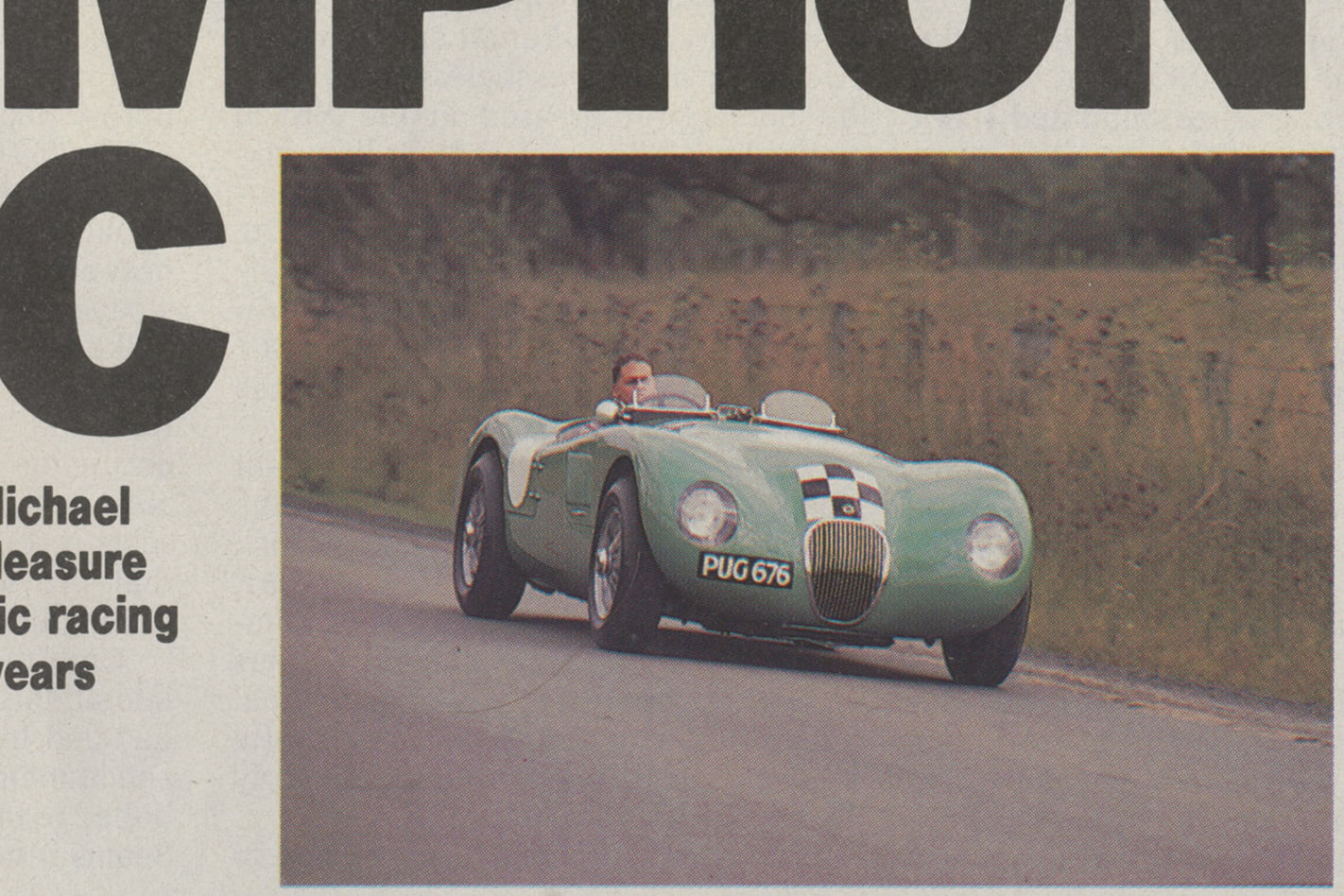

The suede green XKC-021 was despatched from Coventry on September 23, 1952 to Bill Halt in Yorkshire. Halt had built a handy reputation racing an XK120 in British events, and hoped to do more of the same in a C-type. Halt certainly wasted no time in hitting the circuit with his just-registered PUG-676. Its first race was at Goodwood on September 27, in an event won by the C-type of Tony Rolt over that of Stirling Moss. Rolt’s slight advantage on this occasion had been the new A-arm rear end. The following year, Rolt would share a C-type with Duncan Hamilton to win Le Mans.

As only 54 C-types have been built, their individual histories are quite well documented. Or William Marshal! Was also fortunate in being given a number of magazine and newspaper clippings and photographs when he purchased XKC-021 in 1983, but he has found that some of the Jaguar books listing the histories of the cars contain some errors where XKC-021 is concerned.

Hallihan brought the car Down Under the following year and started work on a full restoration. Jaguar enthusiasts turn BRG with envy when they recall that, at the same time, Hallihan also owned the D-type which would later be passed on to Historic racing identity Ian Cummins. Hallihan’s work on the C-type – all of it top-notch, according to the present owner – proceeded gradually until 1983, when he advertised it for sale still in pieces.

Its new owner was something of a contrast to the placid Hallihan, who delighted in owning classic Jaguars but made no real demands on them. Dr Marshall had already scribbled a C-type onto his shopping list, along with other 1950s Le Mans cars like D-types, Maseratis and Ferraris. On his own admission, he bought the Hallihan C-type “because it was available”.

The car was then entrusted to Barry Graham and Paul Corner, who rebuilt the mechanicals and fabricated some missing bits like the door hinges, while the body panels went off to A&J Corben in the Sydney suburb of Hurstville. Things didn’t really get started until August 1986, and, as if to echo the car’s designers, the full rebuild was finished in only five months.

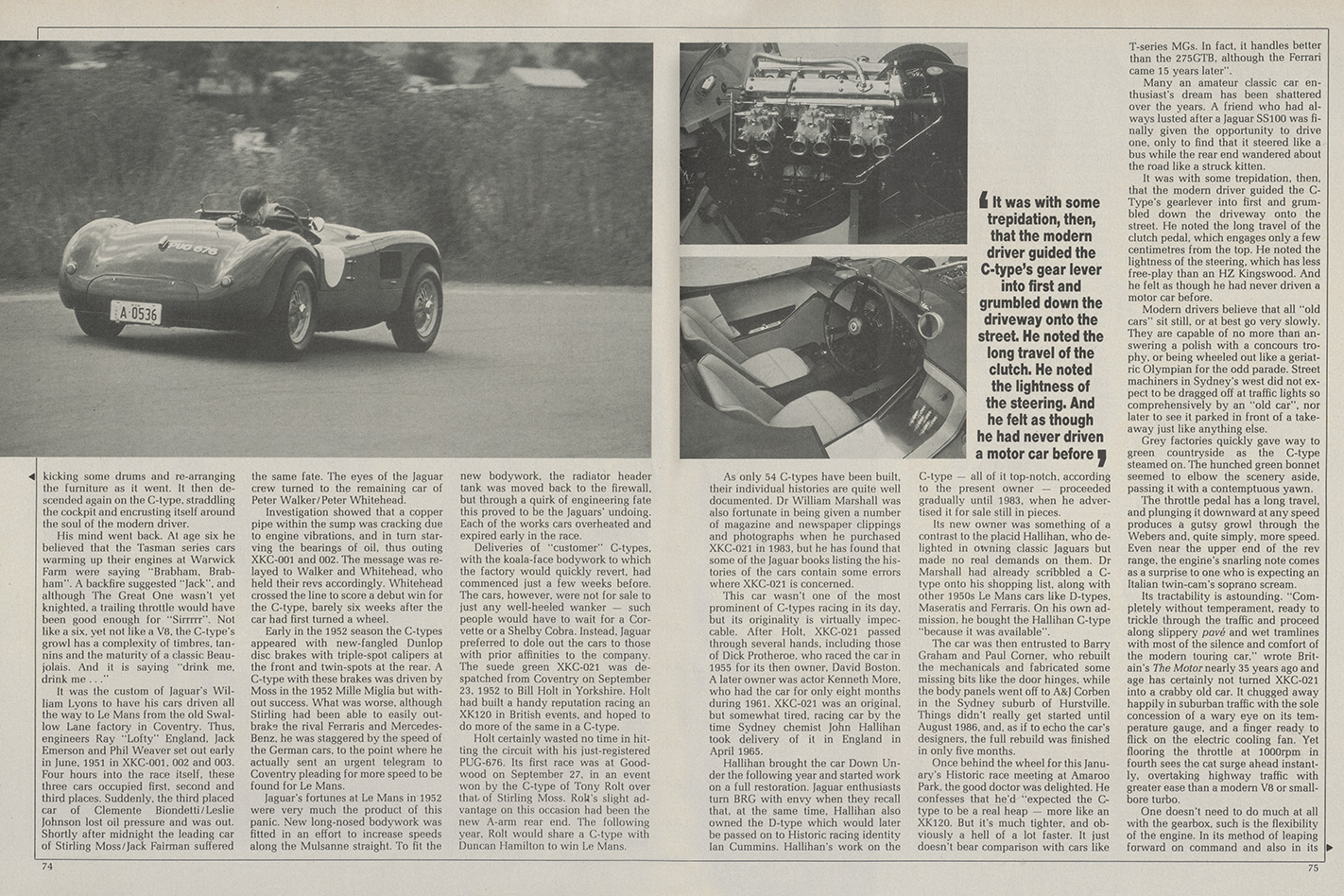

Once behind the wheel for this January’s Historic race meeting at Amaroo Park, the good doctor was delighted. He confesses that he’d “expected the C-type to be a real heap – more like an XK120. But it’s much tighter, and obviously a hell of a lot faster. It just doesn’t bear comparison with cars like T-series MGs. In fact, it handles better than the 275GTB, although the Ferrari came 15 years later”.

Modern drivers believe that all “old cars” sit still, or at best go very slowly. They are capable of no more than answering a polish with a concours trophy, or being wheeled out like a geriatric Olympian for the odd parade. Street machiners in Sydney’s west did not expect to be dragged off at traffic lights so comprehensively by an “old car”, nor later to see it parked in front of a takeaway just like anything else.

Grey factories quickly gave way to green countryside as the C-type steamed on. The hunched green bonnet seemed to elbow the scenery aside, passing it with a contemptuous yawn. The throttle pedal has a long travel, and plunging it downward at any speed produces a gutsy growl through the Webers and, quite simply, more speed. Even near the upper end of the rev range, the engine’s snarling note comes as a surprise to one who is expecting an Italian twin-cam’s soprano scream.

Its tractability is astounding. “Completely without temperament, ready to trickle through the traffic and proceed along slippery pave and wet tramlines with most of the silence and comfort of the modern touring car,” wrote Britain’s The Motor nearly 35 years ago and age has certainly not turned XKC-021 into a crabby old car. It chugged away happily in suburban traffic with the sole concession of a wary eye on its temperature gauge, and a finger ready to flick on the electric cooling fan. Yet flooring the throttle at 1000rpm in fourth sees the cat surge ahead instantly, overtaking highway traffic with greater ease than a modern VB or small-bore turbo.

One doesn’t need to do much at all with the gearbox, such is the flexibility of the engine. In its method of leaping forward on command and also in its road manners, the C-type feels mostly like a very light car with a bloody great big engine in it. It requires much pinching of oneself to remember that the speedo is calibrated in miles per hour.

Stirling Moss has written that Jaguars from this era were best suited to smooth, high-speed tracks like Le Mans and Silverstone, and indeed, steering across to the shoulder of the road found the C-type wanting to take a good sniff at the verge, and on fast corrugated corners the rear end is inclined to step offline – sometimes quite alarmingly.

Dr William Marshall attests that the C-type is a delight on smooth racing circuits, where he likes to drive this car very much as it was meant. Paul Corner assumes the air of a nervous mother while Marshall happily tells of his race-long dice with Les Wright’s Buckle coupe at Amaroo in January. A touch between the pair over the crest at Bitupave resulted in shreds of Wright’s rubber being left on the C-type’s knock-on hub, and 61-second laps show Marshall wasn’t kidding .. .

The man has an admirable philosophy. “The car was made to race, that’s what it’s for. It happens that I race to win. I enjoy having it, and I enjoy caning it”. But what if he were to hang the thing on a fence somewhere? “Ah, well, we’d just take it home and fix it. Nothing’s irreparable”. Lines that flow easily from the tongue of one of Sydney’s leaders in reconstructive surgery. Paul Corner, meantime, looks pale.

Acknowledging his enthusiasm, the Panalpina World Transport company and the Australian National Line have got well behind the speed-hungry surgeon, enabling him to accept the invitations that arrive from event organisers across the globe. His aim is to compete in at least one international event each year – “mostly in the Jag. or I may take the Ferrari. The C-type looks like being the thing to beat in its class in the ’88 Targa Florio”, he adds with unrestrained enthusiasm.

Competing overseas will also do no harm to the car’s value. for these events function as the meeting place for the international classic car clique. Like Australia’s three other C-types, XKC-021 is known intimately to hundreds of would-be owners who have never even seen it. Or Marshall says he gets at least one international phone call each week from some well-heeled Briton, Belgian or American begging him to sell it. He admits that his original plan had been to rebuild the C-type and then flog it in favour of a D-type, “but everyone who has driven both cars says that the C-type is nicer to drive. It’s not quite the quickest, though … “

For collectors, choosing a classic sports or racing car often boils down to a choice between history and condition. Australia’s four C-types represent a healthy mix of both. Historic car guru John Blanden owns XKC-041 in Adelaide, an ex-Ecurie Ecosse car which Les Hughes, chairman of the Australian Council of Jaguar Clubs, says is “absolutely magnificent” and rates alongside XKC-021 as being two of the most original C-types.

Remarkably, the sister car to Blanden’s XKC-042 resides in Melbourne and is, according to Les Hughes, “basically original but a bit tired”.

The weight of the C-type’s history and present-day value became entirely secondary as we passed trucks and traffic on the freeway taking us home. We were struck by the realisation that modern motoring is pure folly. If we wanted to change lanes we simply did it. If we wanted to see behind, we turned our heads and enjoyed the uninterrupted view. If we wanted to get in or out of the car, we did so unhindered by seat belts and door locks. And if we had crashed, we would probably have been killed.

And the fact that we could open three carburettors, accelerate the motion of camshafts and valves, cause the engine to develop more power and thereby make our motor car travel more quickly, all by pushing one single pedal, became a thing of immense beauty.