How the Cannonball crumbled was originally published in the July 1994 edition of Wheels magazine. This year marks the 25th anniversary of the fateful event, which is retold here by journalist, and Cannonball competitor, Paul Gover.

Just after 3pm on day two of the Northern Territory Cannonball Run, Alex Danilo was hustling his Maserati Barchetta south towards remote Aileron on the Stuart Highway. He was in a hurry, dashing to average 223 km/h over a 62.4 km Cannonball Stage.

Much too late, Danilo and co-driver Craig Brown spotted the warning flag and witch's hats for the finish control. He braked heavily and the car skidded on freshly laid gravel at the control area, wiping out the cones as the Barchetta slid past the officials.

Danilo had been lucky and he knew it. As soon as he arrived in Alice Springs for the overnight break he went to talk with Cannonball chief Allan Moffat.

At about 9.30am on day three, Japanese driver Akihiro Kabe lost control of his Ferrari F40 at the finish of the very next Cannonball stage, 95 km south of Alice. This time four people died in the worst crash in Australian motorsport history.

The first of the day's Cannonball stages started at Lasseters Casino in the Alice. The roadside was crowded with well-wishers, and there were 60 and 80 km/h speed limits for the first 10.6 kilometres of the 94 km stage. It meant the supercars at the head of the field had to average around 210 km/h from the time they cleared the restrictions to finish the stage penalty free.

Seven kilometres from the finish, Johnny Kahlbetzer in a Porsche Turbo came across the F40 doddling along at about 80 km/h. There was a brief radio transmission from the Japanese, which he now believes was something about the control point and, as he accelerated past, the Ferrari latched onto his tail.

The cars were seen running nose-to-tail just two kilometres from the stage finish by a property owner who had been to the control less than 30 minutes earlier and seen officials sitting at a card table alongside their Jeep.

The checkpoint was set up just past a gentle right-hand curve, with a newly-laid layby and neat lines of witch's hats, and could be seen on the long straight leading to the finish.

Kahlbetzer says he was running to time and was surprised when Kabe overtook him, at a speed he estimated between 200 and 220 km/h, just before the gentle right-hand sweeper.

"They overtook us at the last second; it was definitely their mistake. As soon as I took my foot off the accelerator, the F40 went past," Kahlbetzer said.

"He started to brake, he pulled in front of us still under brakes, then he went off to the left. Then he hit the gravel - it looked like tar but it was loose - lost control and then he went back on the highway.

"There was a grey vehicle in front of us and we thought he was about to hit it but he didn't. At that stage I thought he had everything back under control.

"He then swerved off to the right-hand lane and speared off into the marshal's area. I don't know if he was braking, or what was happening at that stage."

The skid marks showed that the F40 slewed sideways with the brakes locked, and speared into the parked Jeep with enough force to move it two metres into a Commodore sitting alongside.

The trip odometer in the wrecked Ferrari showed 103 km. On a 94km stage, this adds weight to the theory that the two Japanese were confused about the exact location of the control and their average speed.

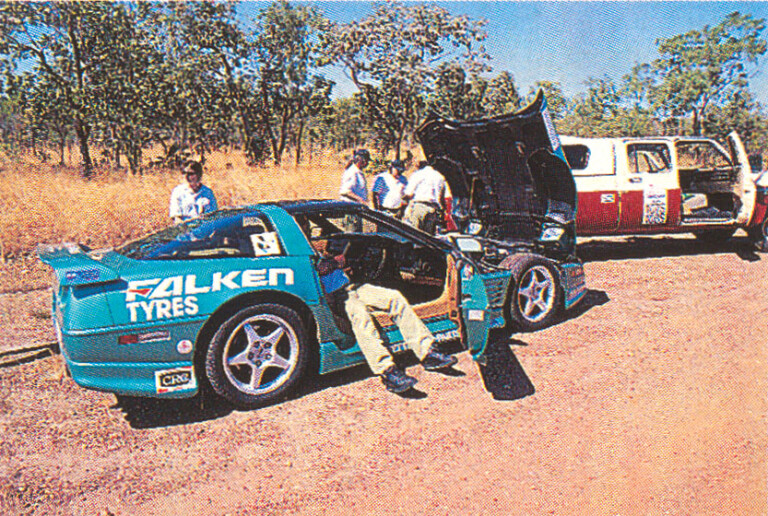

.jpg)

Kabe was killed in the impact, probably banging heads with co-driver Takeshi Okano, and two officials - Tim Linklater and Keith Pritchard - also died instantly. Within minutes, despite the attention of several doctors in competing cars and ambulance officers quickly on the scene, Okano succumbed.

"I just can't imagine what took place," Moffat said later.

"There are 100,000 other spots on the highway where you could have believed this could happen. This certainly wasn't one of them.

"You couldn't actually believe how anybody could actually be killed in it."

The snap judgement was that Kabe, a millionaire Tokyo dentist who indulged himself in a collection of nine classic cars including a Ferrari Daytona, was out of his depth in the Cannonball. His F40 had been clocked at better than 280 km/h in Flying Mile competitions over specially closed sections of the Stuart.

One of the dead officials had told his father that the Japanese was a maniac who was going to kill somebody on the Run.

But other drivers said they saw no signs of stupidity. Kabe told me the night before his death of experience driving the F40 on the Suzuka, Fuji and Tsuba racetracks. We arranged a longer talk during the lay day at Yulara, when our outpaced LandCruiser, car 72, would take a breather with the F40.

The Cannonball Run - none of the organisers called it a race, although news reports were quick to jump to that judgement - was planned as a high-speed dash from Darwin to Yulara and back, taking advantage of the unrestricted roads in the Territory.

It was heavily backed by the NT government whose chief minister, Marshall Perron, is a well-known car enthusiast.

It was seen as a potential tourist drawcard and Moffat was enlisted as head of the organising team, in his first venture into event management. Pre-event publicity promised a string of exotics including a Jaguar XJ220, several Ferrari F40s, and perhaps even a McLaren F1, and with entries at $7500 a vehicle the eventual line-up combined exotica, hot-rodded moderns and outdated muscle cars. The star performer was Kabe's Ferrari.

The event used two types of competition, Flying Mile runs over completely closed sections of highway and Cannonball stages where crews had to maintain a pre-set average speed over a particular distance on ordinary roads with regular traffic. For the rest of the 3800 km route, about 75 percent, crews were effectively touring under NT traffic rules, with no effective speed limit outside towns.

The Cannonball was officially sanctioned by the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport, but its approval was very late. There was no route check - normal even for a low-grade club rally - and safety precautions and checkpoint operation varied from the normal procedures for CAMS road events.

According to CAMS, it had stipulated a limit of a 140 km/h average on Cannonball stages but this was never confirmed by the organisers. Even the slowest cars had to average better than 130 km/h on Cannonball stages.

On day one, averages for the fastest entries - the Supercar Exotics - were 138.59 km/h over 70.5 km and 169.37 km/h over 98.8 km. These rose to 165.2 km/h over 94 km and 200.5 km/h over 137 km on day three.

Even with the best intentions of the NT government, and the organising team under Moffat and Graham McVean, there were questions about safety well before the start. The only entry provisions - beyond the $7500 fee - were a valid driver's licence and a fast car.

Helmets and fireproof suits were recommended only, and safety scrutineering for the cars was held the day after drivers qualified in a sprint at Darwin's Hidden Valley racing circuit where the F40 hit 228km/h.

Gregg Hansford, Bathurst 1000 winner and former rally driver, was worried from the prologue and later tried in vain to talk to Moffat about several issues - including radio procedures for competitors and control layouts. He said: "I was worried about safety the morning we left Katherine. It was 7am and there were lots of people driving to work, and the police radioed through to slow the field down after the first half dozen cars. You can't do an event like that with the roads open to the general public.

"They should have had the ends of sections like a rally, with a flying finish and then about 500 metres to the control point to stop people wanting to go fast for the last kilometre to get in on time. You shouldn't be trying to get in on time in a 60km/h shutdown zone."

On the positive side, the NT administration arranged for verges over the full length of the Stuart and Lasseter Highways to be mowed and there was a daily check for animal carcasses to discourage birds. A small army of police and volunteers manned road junctions. All competition vehicles had to carry CB radios and Larry Perkins flew overhead in a supervision aircraft.

Before the start, Kabe posed proudly on Darwin wharf with his F40. Inside the driver's door was the hand-written message, "To my friend Kabe san. Good luck always. Allan Moffat. Cannonball '94". He and Okana wore bright red nomex driving suits, reserving their helmets for the Flying Miles, and did not have a rally navigation computer to simplify calculations in the Cannonball Stages.

Day one brought delays at the Flying Mile and problems with navigation, with inconsistent distances and sloppy directions which meant cancelling the results of one Cannonball stage. At Katherine, Kabe was presented with the first Top Gun award after clocking 284km/h in the Flying Mile. Moffat joked that the F40 could never hit such speeds in the Ginza.

Little more than a day later, Kabe's fatal crash became front-page news across the country and flashed around the world. With a Territory election just over a week away, it also became a major political football.

Moffat was one of the first on the accident scene, taking over to keep the remaining Cannonball crews moving towards Yulara. The day's second Cannonball stage was run, but the Flying Mile was cancelled.

After talking with the NT administration, the Moffat team continued the event, but under a blanket 180km/h speed limit for everything but the Flying Miles. There was a closed-door drivers' meeting too, and Moffat threatened journalists competing in the event against using anything which was said at the gathering. Moffat and Superintendent Terry Ey, the head of Territory traffic police, spoke and afterwards drivers were issued with CAMS licences.

The return leg to Darwin went smoothly and the first - and perhaps last - Cannonball Run was won by the Porsche 911 Turbo of Ron Conrad. The trip back took crews past the site of the crash. Three bunches of flowers marked the spot.

After the event, Moffat made no comment. But his words at a press conference the day before the start were prophetic.

“Just because you drive a Ferrari, doesn't make you a Ferrari driver," he said.

COMMENTS