Commodore has been Holden’s hero on the track since 1980.

Sustained success on the track was inexorably linked with Commodore’s fortunes in the marketplace, imbuing each series with a sporty image. Racing has been imbedded in the DNA of every Commodore – especially the V8 models – and associations with race-bred performance were sustained by direct links with the Holden Dealer Team and the Holden Racing Team.

That halo effect has remained during Commodore’s sales decline in recent years, with V8 performance versions accounting for up to 50 per cent of sales of mainstream models while demand for HSV variants has remained strong.

Road and race Commodores have shared very little in common for more than a decade as the Supercars technical rules have moved from racers built around production body shells to control chassis and common key mechanical components beneath faithful replicas of road car body shapes.

Supercars look like production models on steroids, but the relationship is only skin-deep. Underneath the lookalike body panels – many of which are plastic facsimiles – they’re pure-bred racing machines. But the visual connection is still strong and the Commodore nameplate is by far the most successful in Australian touring car history.

Commodores have been driven to a record 15 ATCC/Supercar crowns and a yardstick 24 Bathurst 1000 victories. They have also scored an all-time high 474 championship race wins (prior to September’s Sandown 500), with 207 of them shared in the past decade by VE- and VF-look machines.

The VE was only surpassed in August when Jamie Whincup scored the VF’s 104th win at Sydney Motorsport Park. Just 11 days before local production ceases on October 20, Commodores will contest the Bathurst 1000 for the 38th time.

It won’t be the nameplate’s last appearance on The Mountain because new-look Commodores, mimicking the appearance of the fully imported ZB, will be racing at selected rounds from next year. Most VFs will likely soldier on in Supercars for another season, but by 2019, there will be no more Aussie Commodores – or Falcons – competing.

The Commodore track legend has been perpetuated and underpinned by a quartet of hero Holden drivers: the late Peter Brock in the 1980s and early 90s; Craig Lowndes in the mid-to-late 90s; Mark Skaife in the early-to-mid 2000s; and Whincup since 2008.

Since Brock, none has arguably been more deeply involved in the evolution of Commodore racers and their most celebrated road-going cousins than Skaife.

After making his name in the all-conquering R32 Nissan Skyline GT-R at the start of the 1990s, he switched to Holden in 1994 and raced Commodores with Gibson Motorsport, Holden Racing Team and Triple Eight Race Engineering until his retirement from V8s after the 2011 enduros.

Skaife won five ATCC/V8 titles – four of them in Commodores – and six Bathurst 1000s – again, four of them for the Lion. He is also third on the all-time list of championship race winners with 90 successes.

The peak of his immersion in developing race and road Commodores was 1998-2008, a decade that began with him joining HRT full-time alongside Lowndes and becoming involved with HSV, both of which were owned by the late Tom Walkinshaw’s TWR racing and automotive engineering empire.

Skaife dominated V8 Supercars from 2000-02, which is now remembered as HRT’s golden age, and increasingly consulted to Holden and HSV on product development. In the wake of TWR’s collapse in early 2003, he bought HRT from Holden and, by all reports, on very favourable terms.

It was during his reign that the factory team embarked with Holden on the development of the Supercars version of the VE, the biggest Commodore racing project ever. Concurrently, as a Holden ambassador and board member of HSV, he helped hone the driving dynamics of the all-new, all-Australian VE production models and HSV’s E-Series range.

All would be outstanding successes, but by the time the VE hit the track in ’07, Skaife’s influence was in decline. Walkinshaw wrestled back complete control of HRT the following year, pushing him into retirement from full-time racing.

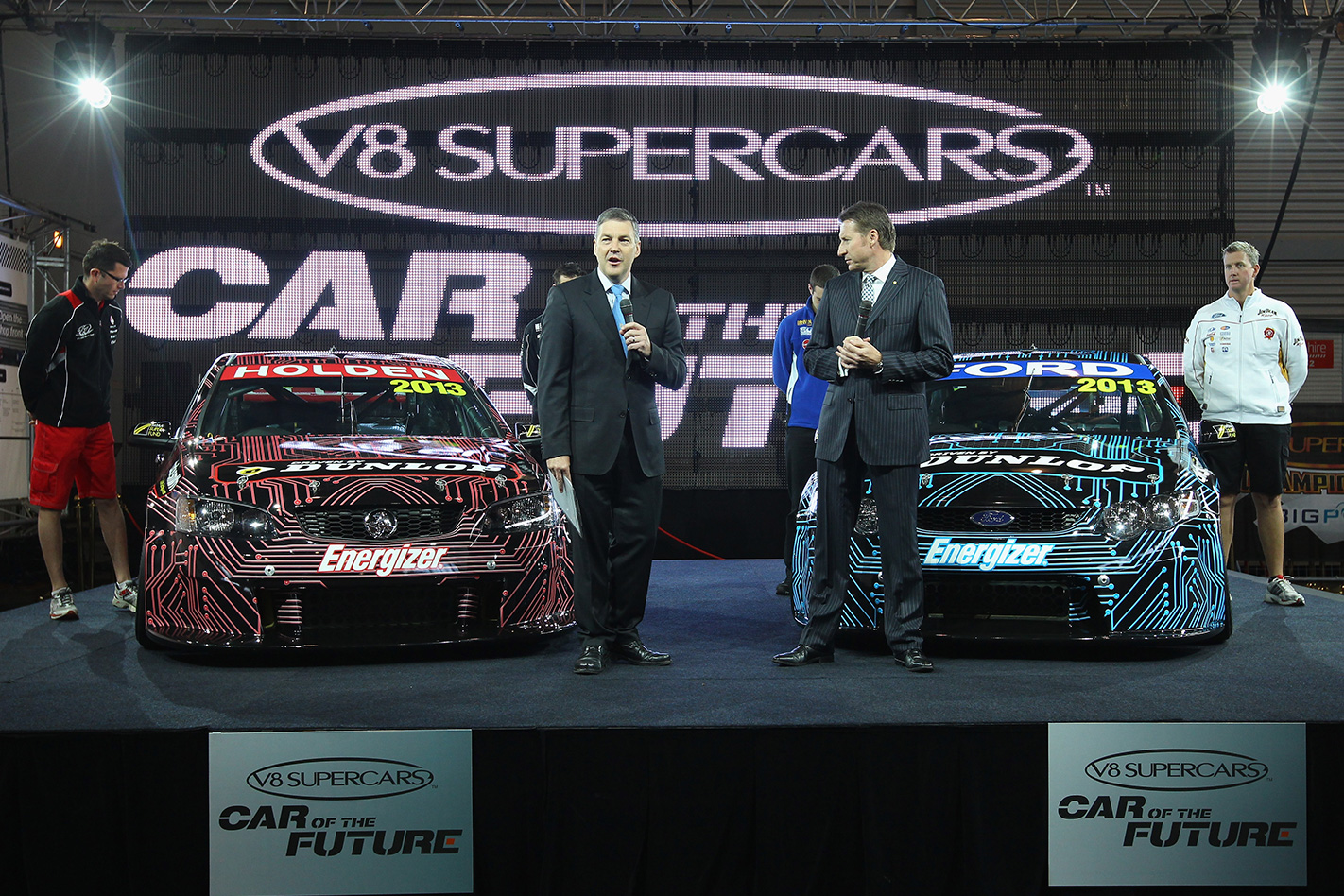

His roles at HSV and Holden also wound down as he moved into senior advisory positions with Supercars and established himself as an authoritative TV commentator. Skaife indirectly determined the VF’s successful racing succession as the architect of the ‘Car Of The Future’ rules, which ended the two-decade Commodore/Falcon duopoly by opening Supercars to other brands.

It was also a radical change to the V8 racers’ relationship to their road-going namesakes, dispensing with the last vestiges of manufacturer homologation. Skaife, 50, is best known these days as the analyst/pundit on Supercars broadcasts.

He has varied business and philanthropic interests outside racing, but the sport remains at his heart, as evidenced by the posters commemorating so many of his successes that adorn the walls of his office in Melbourne’s upmarket suburb of South Yarra.

It is in this shrine to ‘Skaifey’ that we discussed his key roles in the development of one of the greatest competition Holden Commodores of all time and also the most transformational HSVs in the company’s history. With the VE racer, the track image of the most important Commodore in history – and also the most expensive to develop – was critical.

Holden executives were incredulous when they learned that the cabin had to be shortened to meet the dimensional restrictions of the new rules. The solution was to cut 96mm from the roof and side pressings, and shorten the rear doors, which involved new scaled-down stampings made with the sole purpose of being used on the race cars.

“My discussion with [then Holden managing director] Peter Hanenberger and [marketing boss] Ross McKenzie regarding taking 96mm out of their ‘Billion Dollar Baby’ was one of the hardest conversations I’ve ever had,” Skaife tells MOTOR. “To make the car fit the regulations we had to.

We’d worked out that the best spot to knock the 96mm out of it was in the rear doors. So we had to shorten the rear doors. “I’ll always remember, we’re sitting in this sort of lounge in the virtual reality centre, the racecar’s up on the virtual reality screen – and here it is now with the 96mm out of it.

You should have seen their faces. ‘You guys have got to be kidding! What sort of drugs are you on? You think you’re going to chop 96mm out of the car we’ve just spent a fortune on?’ “Getting that through was harder than buying the team. It was one of the most serious GM discussions I’ve ever had.

But we got it through and Holden did a big batch of shortened rear doors. It all worked out beautifully for us. There was a lot of work and a huge amount of effort from all parties to get that through the system, make it comply with the regulations and then develop it into a great racecar.”

Much of the VE racer’s aero kit – front air dam and splitter, sculpted sills, and rear wing and diffuser – was developed on the high-speed bowl at the Lang Lang proving ground. Skaife would often do double duty, assisting HSV engineers to sort the suspension of the VE-based E-Series on the ride and handling course on the same day.

“I was working very hard with the HSV engineers on the new Clubsport and GTS, etc,” he says. “And over in racing-land, the pressure was on to get the design modifications made, get the car on track and develop the aero package. We actually built an aero test car, which became my first VE racecar.

We were down at Lang Lang a lot, doing a lot of aero testing on the banked track and also a lot of HSV stuff. “So some days I’d be down there with a couple of HSV cars to drive around the ride and handling track, and then we’d stay there for the rest of the day and do racecar stuff.

So it was a really busy period and, to be honest, very integrated between Holden, HRT and HSV. There was a very strong, powerful bond between the three organisations in that period. “HSV and HRT were joined at the hip. The race team was a big part of the marketing and DNA of HSV.

And that wasn’t ponytailed agency talk. That was real. I still think the ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ proposition applied to HSV.” HSV and HRT were brought into the VE program from the early stages to more fully integrate the racing and performance-car arms, for which Skaife reveals the engineering and design teams at Fishermans Bend had given unprecedented consideration.

“[Then HSV boss] John Crennan and I were invited in in the very early days to look at what VE’s plan was,” he says. “The critical dimensions were up on the wall and [design chief] Mike Simcoe took us through that plan. I remember noting that the front wheels were right at the corners.

That was great for the racecar and helped improve the precision of the HSVs. Simply, with a big V8 car, the further forward you put the front wheels and, effectively, the front axle centre line, the better it will be. It was very BMW-like and when you look at the VE, for a big car, it certainly has the front wheels far forward.

“Also – and not many people know this – the great thing from Holden’s design standpoint was that there were four variations of the VE architecture – one for the base model, one for SS, one for Calais and an HSV version. So from day one they put HSV in that mix, which was fantastic.

That’s why the cars came out so beautifully – the integration was great. “It was the simplest things, like being able to change the instrument font, that was there right from the start. The ability for us to change door trims and all the other points of difference. Different steering wheel from day one.

All that stuff was allowed for. The bespoke tail-lights and the gill behind the front wheel openings. They were really nice treatments that made the E-Series really stand out from the normal VEs.”

According to Skaife, Holden’s clever base design – and Tom Walkinshaw’s approval of by far the biggest budget for a new model range, running to more than $20 million – meant the E-Series in 2006 was a turning point for HSV.

The new level of sophistication made them genuine value-for-money challengers on performance to the BMW M5 and Mercedes E55 AMG, against which the E-Series was benchmarked. “Because Holden had done a really good job with the fundamental architecture, their car was going to be good,” says Skaife, casting his mind back.

“I remember saying to the HSV engineers of the day ‘We can’t sit on our hands here. They’re going to bring out an SS that’s really going to a sensational car.’ And it was, forcing HSV to raise the bar with the Clubsport. VE forced HSV to step up another level and that kept everybody sharp.

We needed to build on what was already a good car and achieve the right level of differentiation. “And all of a sudden, we went into this market where we were saying ‘If you’re not a brand snob, you’d definitely buy an HSV E-Series’. Value-for-money, day-to-day, they were BMW- and Mercedes-esque.

The M5 and E55 became the new targets. They were the cars we measured against.” Interestingly, Skaife credits a MOTOR-arranged test at the famed Nurburgring Nordschleife in 2000 for his realisation that HSVs could be more than hotted-up Holdens.

A VT II GTS 300 – boasting the Callaway C4B version of the 5.7-litre Gen III Chev V8 producing 300kW/510Nm – was dispatched to Germany to duke it out with a BMW M5 and Mercedes E55 AMG on their homeground at ‘The Green Hell’.

Skaife invited his former ‘Godzilla’ co-driver teammate, Swedish touring car star Anders Olofsson, to handle the driving duties as an impartial tester. The result convinced Skaife that HSV could build a genuine Euro-basher. “For me, the real step up was when we did a test at the full Nurburgring for MOTOR with the first of the Callaway-engined GTSs,” he relates.

“We took a 300kW GTS and compared it with an E55 AMG and an M5 BMW. I called Anders Olofsson and said ‘Anders, you’ve won at the Nurburgring, I don’t know the track from a bar of soap, and I don’t want it to look like it’s a Mark Skaife-contrived result.

Can you come and be the independent test driver of these cars?’ “So we spent a couple of days at the Nurburgring testing those cars and, for me, in my absolute heart of hearts, it was the first time you could say this is actually a Euro-beater, this is a proper thoroughbred performance sedan.

It was actually faster in the dry and the wet over a lap than the M5 and E55, which was pretty cool. Anders asked me ‘Has this got traction control?’ I said no, but the rear suspension geometry was so good that on all the corner exits, he was blown away by how much throttle you could use.

“I reckon that was the game changer. The 300kW GTS enabled us to aspire to something much better. The level of detail and integration set the stage for the E-Series.” With Aussie Commodores having been such a big part of so much of his life, Skaife is unsurprisingly sad to see the end of the locally made Lion along with the rest of the car manufacturing industry.

“Oh, it’s gut-wrenching,” he laments. “I worked with Holden during its greatest and most successful period. What I still have trouble digesting is that we’ll no longer be building these cars locally. Clearly, there’s a heartfelt concern for so many of those employees around that part of the business, but also just the simple quality of those cars.

“Every time I go to Avis, it’s in my profile to get a Commodore. I got into an SS recently and it had done 25,000km, and I actually said to the guy when I handed it back ‘What a good car’.

If you take all the emotion out of it, the quality of the Commodore makes you realise it’s such a travesty that there’ll no longer be an Australian car of that type. It really is a bitter pill to swallow.”