The allure of the Honda S2000 is a peculiar one.

To speak personally, it’s always been one of deep respect, if anything, falling somewhere short of outright fandom.

As someone who grew up living and breathing all things ‘golden era JDM’, Honda’s technical masterpiece always hovered in my periphery.

Unlike many of its peers, it was never known for any notable period motorsport accolades, and it was never in the same conversation as GT-Rs, Supras or the other turbocharged powerhouses.

Strip away all the clout and hype so rife in today’s late-model Japanese car scene, and the Honda S2000 has always been known for one simple thing.

Being a bloody brilliant driver’s car.

Then why, when speaking to the owner of this meticulously curated example you see before you, did he admit to feeling somewhat underwhelmed by that initial test drive around the block? It’s a familiar story I’ve heard from multiple owners over the years.

Well, just like that famous tachometer-tearing engine, this car is all about the heights. And the deeper you dig under the surface, the clearer it becomes that the path of bringing this car to market was an engineering-led one, barely influenced by the marketing department, and that the development choices for this unique vehicle were singular and deliberate.

In today’s age of modular platforms, technical alliances and joint-venture development, the S2000 emerges as a statement of capability and a feat of engineering that’s unlikely to ever be repeated.

The S2000 appeared at a time when Honda’s enthusiast portfolio was at an all-time high. The first-gen NSX was still being sold and gems like the EP3 Civic Type R, the Integra Type R and the Euro Accord Type R were in showrooms. In ‘99 the company even unveiled the astonishingly agile Stream seven-seater, replete with K20A VTEC and a five-speed manual.

Sadly, the good days weren’t to last. The S2000 represented Honda’s 50th birthday present to itselfand when its lifecycle ended and production ceased after a ten-year run, there followed an explicit pivot towards more fuel-efficient and economical cars, kicking off Honda’s dreary phase, with no successor to the NSX in the pipeline at that stage, and the iconic Civic Type R going through its awkward teenage years with the sharply styled but soft-boiled, torsion-beam-rear FN2.

The fact that much of its technical merit, let alone its nameplate, was never passed on to a successor makes the S2000’s story all the more beguiling. While much of the engineering was done in-house, you might find it surprising that the roots of the S2000’s design have an Italian connection.

The S2000 appeared at a time when Honda’s enthusiast portfolio was at an all-time high.

Pininfarina was commissioned by Honda in to produce two roadsters for the 1995 Tokyo Motor Show. One of them was a conventionally styled two-seat sports car called the Sports Study Model. The concept car boasted a 2.0-litre inline-five (likely a Honda single-cam G-Series used in various Japanese-only models), perfect 50:50 weight distribution, and power going to the rear wheels.

You can see a clear link to the eventual S2000 in the concept’s arrow-straight beltline, convex surfacing and long-bonnet, cab-back silhouette. The production S2000 emerged a tamer looking machine in comparison to the dramatic concept car, but its underpinnings were no less advanced.

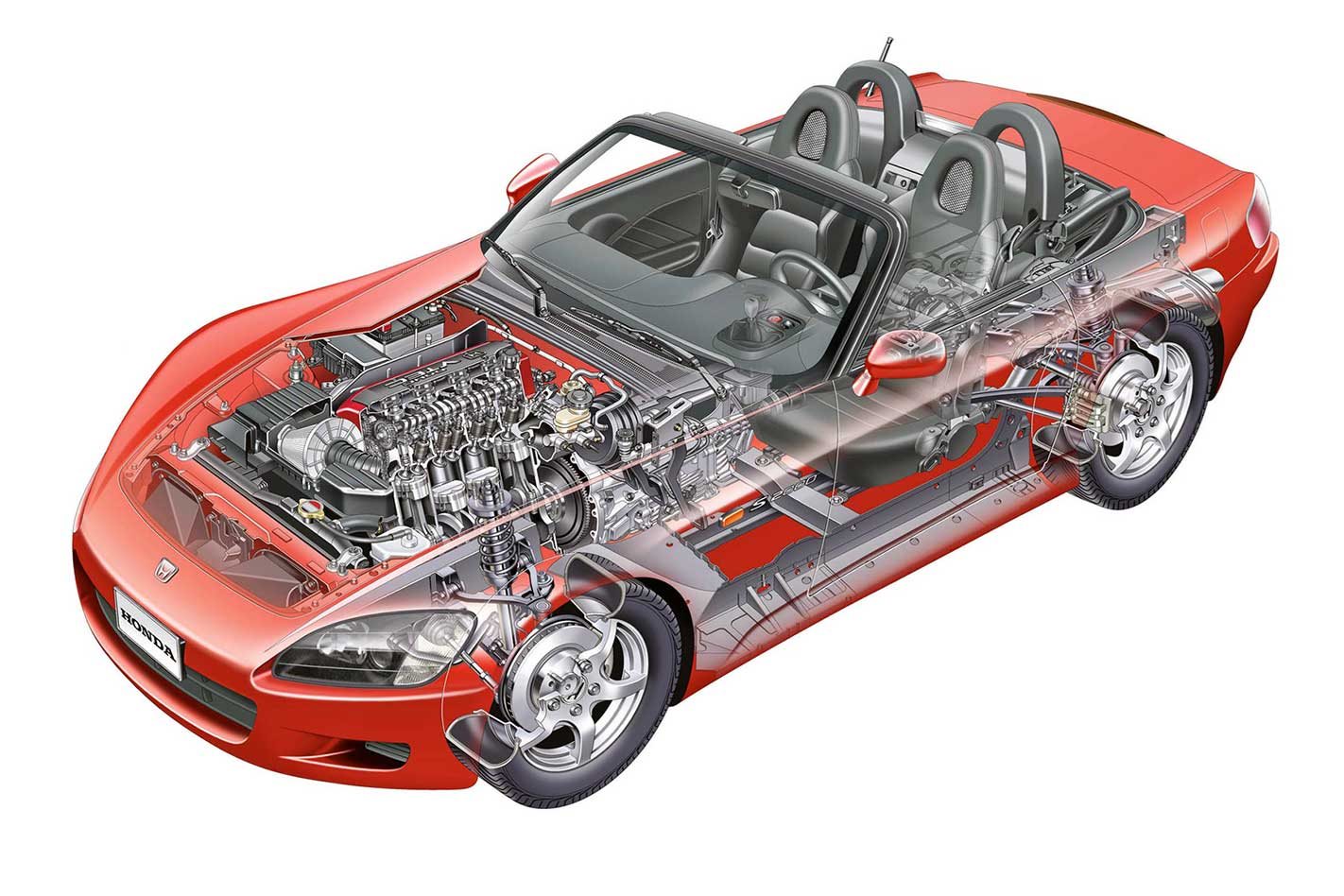

As an open-topped sports car, Honda engineers went to great lengths to ensure that body and torsional rigidity would be comparable to an equivalent fixed-head vehicle, with Honda being an early adopter of aluminium construction, and underpinning the S2000 with a highly rigid ‘X-Bone’ chassis, with a large structural spine running the centre of the vehicle.

The S2000’s chassis was claimed to be lighter and stronger than virtually all sports car rivals of the time, delivering a 2400mm wheelbase with the driver’s hip point seated perfectly at the car’s longitudinal axis.

The ‘spine’ is paramount, and looks almost double the width of the similar design adopted by Mazda’s current ND MX-5. The S2000’s windscreen itself was also a structural element.

The Italian concept’s NSX-derived five-speed automatic was replaced by a six-speed manual transmission come production, but Honda’s flagship supercar did lend its double wishbone suspension design, constructed out of ductile iron with coil sprung gas-filled shocks at each corner and anti-roll bars front and rear.

A large contributor to the S2000’s perfect weight distribution was its front-mid engine positioning, centralising the car’s mass and contributing to a low yaw moment and increased input responsiveness. In fact, strip away the body, and the rolling chassis of the S2000 is remarkably petite, with that classical long-bonnet silhouette belying the fact that the exotic four-cylinder engine was mounted entirely behind the front axle.

And what an engine that was.

In today’s booming aftermarket crowd, Honda’s F20C isn’t exactly known as a cost-effective base for power builds, but in factory form, it was nothing short of a technical masterclass.

The 2.0-litre’s 9000rpm redline made international headlines, but its JDM-spec 184kW output was good for 92.14kW per litre, for a time, the highest specific power output of any normally aspirated production car. It took Ferrari and its 2009 458 Italia supercar (at 93.17kW per litre) to wrest that title away.

It must be noted that Australian-spec cars made a slightly lower power output, courtesy of a marginally lower compression ratio, given the car’s requirement for 95 octane and Australia’s-then limited access to high-octane fuels. It remains, however, a testament to Honda’s ingenuity that, aside from ultra-low-volume outliers like the BAC Mono, the Honda S2000’s engine remains the most powerful atmo four-cylinder series production engine, regardless of size, ever produced.

As the industry trends towards the undeniable efficiency and performance benefits of turbocharging and electric augmentation, there’s every chance it will remain as such.

It’s here that we should nut out the particular nuances between pre- and post-facelift vehicles, denoted by chassis designations AP1 and AP2, respectively. The most notable change overseas was an increase in engine displacement from 2.0-litres, to 2.2-litres.

The larger engine yielded no more power, utilising the same 87mm bore diameter. Extra swept capacity came courtesy of shifting from an oversquare 84mm stroke to an undersquare design with a longer 90.7mm stroke. This delivered the same piston speed mid stroke at 8000rpm as the original 2.0-litre engine did at 9000rpm, subsequently producing peak torque 1000rpm earlier, meeting Honda’s aim of improving ease of use and everyday tractability.

It remains a testament to Honda’s ingenuity that the S2000’s engine remains the most powerful atmo four-cylinder series-production engine, regardless of size, ever produced.

It makes sense on paper, but the larger 2.2-litre unit is widely regarded as a less frenetic, and less desirable, engine.

The good news, however, is that Australian-delivered S2000s never came with the updated 2.2-litre engine, retaining the gloriously highly strung 2.0-litre ‘F20C’, but gaining other ‘AP2’ updates including new tail lights and a soft fabric roof fitted with a rear glass window, instead of plastic. Other developments included softer spring, shock and anti-roll bar rates, larger 17-inch wheels, less aggressive rear toe settings, uprated brakes and the switch to a drive-by-wire throttle.

With AP2 production commencing in 2004, only a few hundred were ever delivered to Australia, with sales having slowed from its debut-year peak of over 500 in its first full year on sale in 2000.

That’s the crux of the S2000. It never relied on the latest tech like a twin-turbo, four-wheel-steering GT-R.

That largely explains why residual values never quite depreciated to the same bargain status as other Japanese sporting contemporaries. Despite a global production pool exceeding 110,000 units, Australia accounted for approximately 1800 sales between 1999 and 2009, a mere 1.6 percent of global production.

And that’s the crux of the S2000. It never relied on the latest technology like a twin-turbo, four-wheel-steering GT-R, or made use of any mould-breaking technology like a Mazda rotary. Instead, Honda’s millennial roadster hung its hat on its unmitigated focus on the driving experience.

Seat yourself in the snug cabin, and you can instantly see why. The tactile shift action remains world class and the gear lever’s proximity to the steering wheel means little time is spent without two hands on the steering wheel.

The same ethos extends to the air-con fan (left) and audio volume control (right) which have also been designed to be flicked with your fingers while still gripping the wheel. Drop down the central radio cover, and it really is only necessities in your field of view.

But, despite being lauded as one of the all-time great driver’s cars, Honda’s S2000 wasn’t without foibles.

Early S2000s have a wicked reputation for spiky on-limit behaviour, with eccentric factory geo, slow electrically-assisted steering and no standard stability control fitment. Owners often complained about accelerated rear treadwear, given Honda’s less-than-economical factory rear toe settings (up to 6mm in AP1, lowered to 3.7mm in AP2).

The S2000 was never about running costs, however. And the vehicle’s biggest market, the US, cared less about Nürburgring lap times than an obsession with lateral G figures. In this context, the S2000’s foibles become deliberate developmental decisions, delivering such a high level of mid-corner adhesion that over-committed drivers were often met with frighteningly large moments if they weren’t keyed into the car.

Further, its headline power output, matched with its modest 208Nm torque output, meant that the S2000 only came into its own when you were wringing its neck.

Honda’s S2000 has always stood confidently on its own, and emerges as an even rarer example of an engineering-led vision brought to market.

In today’s age of platform sharing and parts commonality, the S2000 exhibits a level of specialised development that exceeds that of even some modern junior supercars.

What makes a classic isn’t always about the car or its rarity in and of itself. Sometimes, it’s about the rarity of the ethos behind creating the car. And the ethos behind the S2000 is something quite special. But then birthdays should be indulgences.

It’s just a shame that we may have to wait a very long time for another Honda with its purity of focus.

Some note title here

Honda engaged coachbuilder Pininfarina a number of times over the years, with the Italian firm designing not just the Sports Study Model for the 1995 Tokyo Show, but another, much more art-deco roadster called the Argento Vivo. (see below)

As for road-going Pininfarina-penned Hondas, the storied design house is credited with the Japanese-market Honda City Turbo and Honda Beat kei cars.

? Want more from classic Wheels mags? Pick up a subscription and you’ll have digital access to every single edition since the first issue in 1953.

| Honda S2000 figures | |

|---|---|

| Engine | 1997cc 4cyl, dohc, 16v |

| Max power | 177kW @ 8300rpm |

| Max torque | 208Nm @ 7500rpm |

| Transmission | 6-speed manual |

| Weight | 1320kg |

| 0-100km/h | 6.2sec (claimed) |

| Price when new | $69,990 (1999) |

| Price now | c.$60,000 |

We recommend

-

Reviews

Reviews2004 Honda S2000 performance review: classic MOTOR

Revised, but you’ll have to look (and drive) hard to notice

-

News

NewsHonda is asking the internet what S2000 parts it should reproduce

Japanese car maker turns to the power of the hashtag to get a consensus

-

News

NewsThe ultimate time attack Honda S2000 is up for grabs

Former record holder and multiple WTAC Pro Class contender looks for a new home