WHAT YOU are looking at here is a chimera; an alien shape that could never be replicated today. The low bonnet and cowl would never pass pedestrian safety legislation now. Those would have to be raised, with fresh air over the top of the engine’s hard points. With it, the seating position would inch up by a commensurate amount and that would require a higher roofline. Because of that, the beltline would have to be elevated to prevent the glasshouse looking gawky. That, in turn, adds sheetmetal between the beltline and wheelarch tops, so the wheels need to get bigger and heavier to maintain proportion. And then you realise there’s no chance of replicating the purity and balance of the beautiful FD RX-7. This moment will never happen again.

It’s hard to know whether this pleases Wu-Huang Chin or not. The Taiwanese designer was part of the Mazda North American design team that won a shoot-out against a home team from Hiroshima. Many aspects of the Japanese proposal would end up recycled into the MX-3, but the American design was something very special.

“I first started working on the third-generation RX-7 in 1988,” says Chin. “Soft, organic aero shapes were the trend of the time. Our goal was to develop a timeless design along the lines of the legendary Ferrari and Jaguar sports/racing cars from the 1960s. We pictured in our minds this car being presented at the Pebble Beach Concours 20 years later. However, we did not want to borrow any heritage from others; instead we looked at the Cosmo Sport, the first- and second-generation RX-7s and tried to continue this Mazda rotary heritage.”

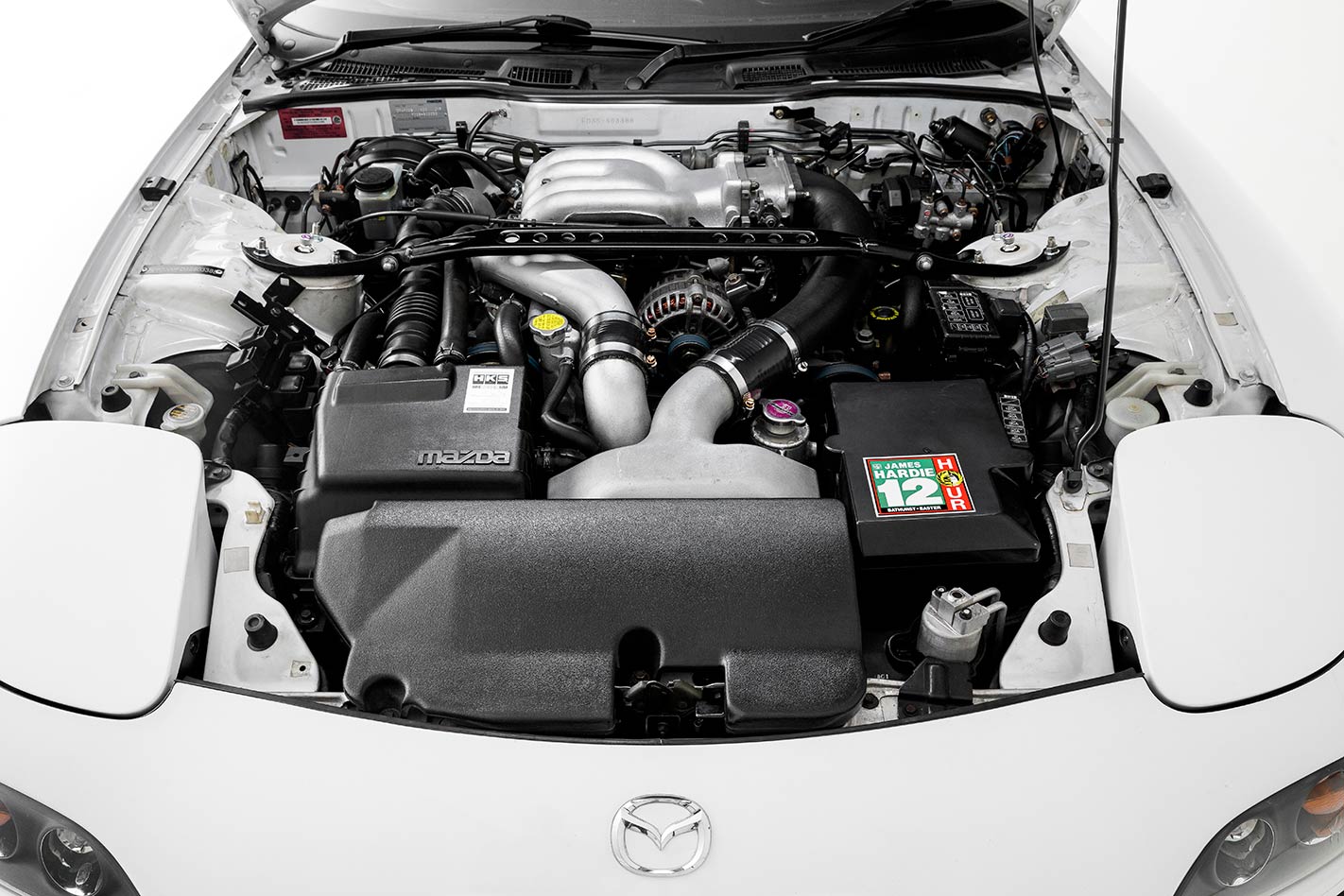

It’s hard to overstate how radical the engineering was here. The FD RX-7 and Cosmo shared a sequentially turbocharged rotary engine, the first production cars after the Porsche 959 to offer this tech. The engine was pushed deep and low into a gaping transmission cone for a surface-skimming centre of gravity. Long before the company’s ‘gram strategy’ on the MX-5, Mazda sought to slice weight out of every RX-7 component. The brake pedal is a tiny aluminium tile, drilled 12 times to further shave weight.

Even the spark plug leads were trimmed to save weight. The dimensions were kept compact; shorter, wider and lower than its predecessor with tighter overhangs and 20 percent better torsional rigidity. For some sort of perspective, the 1230kg Type RZ model is a yawning 311kg lighter than a modern Supra. As far as contemporary benchmarks, the initial power-to-weight ratio was within two percent of the Ferrari 348 and two percent better than the aluminium-bodied, and far more expensive, Honda NSX.

The fundamentals were near perfect. Light weight, a low centre of gravity, fully galvanised body, aluminium double wishbones front and rear, vented disc brakes all round and a clever Power Plant Frame (PPF) that used high-tensile steel to effectively make the engine, gearbox, Torsen differential and rear axle into one unit. An allied benefit of the PPF was additional crush resistance that then permitted the fitment of a larger 76-litre fuel tank without risking it being pierced by the diff housing in the event of an accident. Together, the PPF, the rotary engine and gearbox totalled a mere 374kg.

The twin Hitachi HT12 turbo set-up was fiendishly difficult to calibrate. It required 67 vacuum hoses to finally ensure that there was a smooth handover from one to the other, pressure bled off the primary blower pre-spinning the secondary turbocharger to 140,000rpm before chiming in at an engine speed of just over 4000rpm. Stung by accusations of rotary engine unreliability, Mazda punished the 13B-REW engine in testing, running one unit at 8000rpm for six months while another was accelerated from tickover to 7000rpm constantly for three months. Another test involved taking the engine to its heat threshold and switching it off to see if the turbochargers would cremate themselves, over and over again.

The car first launched worldwide in 1992 and there were three sub-generations of the FD. The Series 6 ran from 1992-1995, followed by a lightly modified Series 7 from 1995-1998. The Series 8 was a Japanese- market-only swansong from 1998-2002 but included the desirable Type RZ and Spirit R models. Wheels tested the RX-7 in October 1992, putting it up against the BMW 325i, the Nissan 300ZX and the Subaru SVX, but as far as dynamics were concerned, it was soon apparent that it was a mismatch. As Mike McCarthy said, “For sheer grunt and go, the RX-7 is streets ahead” and he noted that “the RX-7’s chassis dynamics are mind-boggling. Nothing here comes close.”

Australia received the very special RX-7 SP in 1995, produced to homologate vehicles for the Australian GT Production Car Series and the Bathurst 12 Hour. Only 35 were built in 204kW/357Nm guise, and for many, this is still the ultimate production FD. Selling here for $99,790, it was around half the price of the $189,450 BMW E36 M3R and $218,000 Porsche 993 Carrera RS Clubsport and was a better road car than both the Germans. With a carbon airbox, a lower diff ratio, Kevlar-shelled Recaros, a huge intercooler with manual spray function, bigger brakes and stickier rubber. That and a 120-litre race-spec fuel tank, a modified nose cone and spoiler, 17-inch wheels, a freer breathing exhaust and a re-flashed ECU. The result was a win at the 1995 Bathurst 12 hour (held at Eastern Creek in that year, with John Bowe and Dick Johnson delivering Mazda victory for the fourth year in succession). The car pictured here is the Japanese market Bathurst R spun off the back of the wins in 2001.

While the likes of the SP, the Spirit R and the Type RZ are easy recommendations, virtually any manual RX-7 is worth seeking out. The Touring X auto is somewhat lame, and later Series 8 imports with automatic gearboxes are down 10-15 horses compared to their manual equivalents. Usually the difficulty is finding a relatively unmolested car. In the FD RX-7’s case, that’s virtually impossible. Most owners understandably freshen the look of their car with new alloy wheel designs, and switching the twin-turbo setup for an easier to manage single turbo installation is a popular conversion. This helps get rid of the so-called rat’s nest of vacuum hoses that can spring almost impossible-to-diagnose leaks.

The engine itself is tougher than the internet horror stories suggest, especially if previous keepers have been diligent with correct-grade non-synthetic oil. The oil needs to burn in a rotary and synthetics don’t do this brilliantly, leaving deposits and varnishes in the combustion chamber that will wear the apex seals. A high-zinc content mineral oil that’s changed every 5000km is the way to go. Getting a specialist to perform a compression test is also key. The factory service manual reckons on 100psi for each chamber, and should you see a result lower than 85psi, you could well be on the road to a rebuild.

The RX-7 is broadly heat-intolerant, and hot climates can see the rat’s nest and wiring loom become brittle and unreliable. Same goes for the engine mount rubbers. Replacing the fan switch is recommended for Australia, as the fan kicks in at 124° Celsius, which can be too late to prevent the engine sweltering. Replacing it with an FC switch causes the fans to run at medium speed from a lower temperature. Coolant should also be diligently changed as old, acidic coolant will deteriorate the apex seals.

A good secondary health test of the engine is to connect a boost gauge to the intake manifold and have a mate rev the engine slowly and cleanly. Check that the turbocharger isn’t registering more than 10psi until around 4500rpm. From there, charge pressure will momentarily dip to around 8psi as the second turbocharger spools up and then blip back up to a steady 10psi. Cranking up the boost on an FD RX-7 requires a lot of additional and expensive work on cooling. Some have tried going down this route before deciding that it’s easier to fit a small-block V8 than try to get an FD running high boost reliably. Many RX-7 enthusiasts view this as a particular sacrilege.

Get a well-sorted car and all of the things that made the RX-7 great back in the day still apply today. There’s a fundamental rightness about the decisions made about the car’s dynamics that haven’t aged at all. The qualities of light weight, a charismatic engine, great steering, adjustable handling and a cleanly designed, driver-focused cabin transcend the quarter of a century since the FD RX-7 debuted.

The years have done nothing to erode the appeal of this, the most sensuous of all the Japanese bubble-era super coupes. The FD represents a specific moment in time, but in this instance one that seems to have perpetually sidestepped the undignified ravages of the ageing process. It’s a jewel-like exotic which represents the last of an exceptional line.

SPECS

Model: Mazda FD RX-7 (’92 Aus spec) Engine: 1308cc twin rotor, twin-turbo Max power: 176kW @ 6500rpm Max torque: 294Nm @ 5000rpm Transmission: 5-speed manual Weight: 1310kg 0-100km/h: 6.5sec (as tested) Price: $73,000 then, from $35,000 now