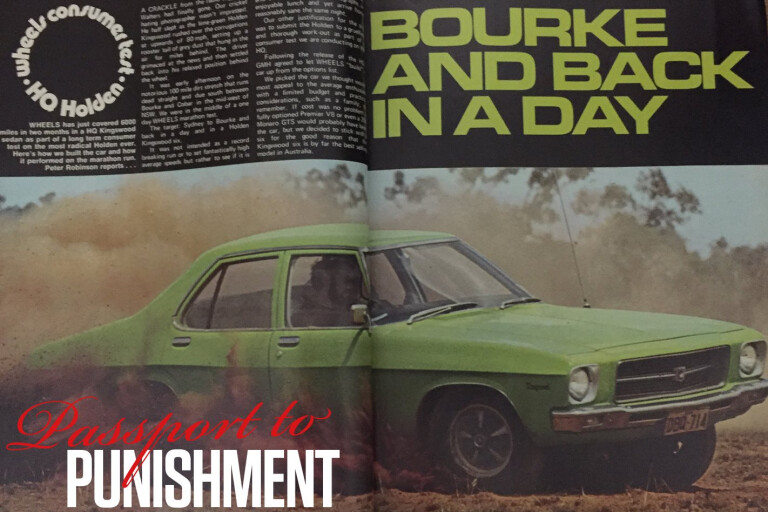

HQ to Bourke and back - April 1972

HOLDEN’s failure to win COTY with the HQ didn’t prevent us from acquiring a long-term Kingswood, carefully optioned by us, for what we called a ‘Wheels consumer test’.

The highlight of our time with DBQ-714 was a marathon drive from Sydney to Bourke and back. Our intention was not to break speed records, or set a high average speed, but rather to see if it was possible to drive 1000 miles in a day, with enough time for lunch and photography. After departing at 4am, we returned to Sydney just before midnight, 1098 miles (1768km) later.

Our HQ had sporting pretensions. Except it didn’t drive that way. It had a wide-ratio gearbox, a slow-revving, inefficient six, low-geared (4.3 turns) and heavy manual steering, and notoriously soft suspension.

The wonderful (before speed limits) Bells Line of Road over the Blue Mountains instantly exposed the HQ’s handling flaws: body float, strong understeer and vague steering. I wrote: “Pleasant to drive slowly but requires a firm hand and big heart to push hard … The basic stability of the HQ is excellent – the problem is simply that the car doesn’t like shifting off line.”

Even by the standards of 45 years ago, neither the performance nor economy were outstanding. Still, we praised the excellent ride comfort, forward visibility (compare the HQ’s thin windscreen pillars with those of today’s Commodore), fine bucket seats, body solidity, superb dust sealing and terrific flow-through ventilation.

Yet it took six years and major suspension corrections before Wheels truly appreciated Holden’s beautiful HQ-HZ range.

VL Director vs Europe - December 1986

THAT THE HDT Calais Director was named after “an indifferent French Port,” in Robbo’s words, did not fully explain why it graced the cover of Wheels December 1986 with the Eiffel Tower looming in the background. But what an incredible image.

Wheels had shipped HDT’s ultimate performance version of the VL Commodore V8 to the UK, via France, to test “The long-held view that Brock’s Commodore could take on the Europeans.”

With a Ford Sierra Cosworth RS500 and a Mercedes-Benz 190E 2.3-16 involved, the line-up represented the contemporary World Touring Car Championship in road-going form – a precursor to Bathurst ’87 – except with an E28 BMW M5, not an E30 M3.

The cars were vastly different. “Relying on a large, lazy engine for its performance, the Calais Director was both the thirstiest and the most flexible,” Robbo observed.

Despite the immense effort invested in transporting Australia’s Finest across the globe, Wheels was far from parochial:

“It doesn’t feel as quick as the Ford or BMW,” said Wheels contributor Gavin Green. “It’s heavy, more difficult to move off line, the brakes are spongy and it understeers.”

The Director’s “styling, ride and handling all reflect a long history of adding-on to a design which basically is now nearly a decade old,” said Robbo, adding that its “shortcomings are the most obvious.”

“The stopwatch doesn’t lie,” he concluded. “Europe, it seemed, had rolled back the Aussie invasion.” Holden’s best wasn’t quite world class, but there was still time.

Trial by torture for the VN Commodore - October 1988

‘OUR TOUGHEST ever road test’ wasn’t devised on a whim. Rather, October 1988’s 21,000km, VN Commodore versus EA Falcon cover story went in search of the answer to one burning question:

“We needed to know whether, after 10 years of playing second fiddle not only to the Falcon but also the indelible memory of the immortal Kingswood, the new VN was good enough, tough enough and really big enough to put Holden back in the winner’s circle,” wrote Wheels’ technical editor, Mike McCarthy.

Emerging from the brink of bankruptcy, Holden had developed a VL successor that put an Opel Omega/Senator body on a stretched and widened version of the old car’s platform. And clearly, Joe Public wanted answers. “Break the bastards! That’s what the man said when he learned Wheels was testing the VN Commodore and EA Falcon,” Micmac relayed.

The trip took in a huge, C-shaped loop, inland from Southport in Brisbane, then south via Birdsville, and skirting Broken Hill to Sydney via the ACT.

When the red dust settled, Micmac had this to say: “We tried … but the bastards wouldn’t break. We gave ’em heaps, flogged ’em through the dirt, stone-washed their bellies and muscled ’em through the mud. Though bruised here and battered there, they took everything we and the outback threw at them. We can’t think of many other standard models we’d try to drive so far, so fast, so hard with such confidence.

“They really are built for Australia ... but one is better than the other.” The VN.

HSV SV5000 in Europe - June 1990

YOU DIDN’T have to read to the end to get the gist.

Wheels’ second instalment of An Aussie Abroad revealed on the opening spread that “Australia’s SV5000 out-performed three sweet Europeans. But the raw lump from Down Under lacked a little refinement.”

A familiar conclusion, perhaps, and certainly a parallel for the Aussie character itself – rough, yet endearing – and that’s how HSV’s SV5000 had charmed us up to that point.

For our June 1990 cover story, we made for the Mother Country with something to prove. As author Robbo put it, “when you have the hottest V8 automatic to come out of Australia, the temptation is overpowering. Not just to compare it with Europe’s best – but to do it on their turf.”

The cast included sports/luxury sedan cornerstones from BMW (E34 535i) and Mercedes-Benz (W124 300CE-24), while a Vauxhall Carlton GSi provided the Pommy context for our (Opel-derived) Commodore.

Things got off to a good start. “European high-tech is no substitute for Australian cubic inches,” Robbo exclaimed.

The SV5000 blew its rivals away down the standing 400m, laying down a 15.3sec time. “None has an answer for the immediate acceleration of the Commodore, the product of instant torque from a rumbling V8”.

The fact the SV5000 was not considered the dynamic standout was no surprise. But the conclusion still rings true in today’s VFII Commodore. Mused Robbo: “If I wanted to drive any of these cars for pure pleasure over a demanding road I’d have no hesitation in choosing the fearless Commodore. Refinement and finesse can sometimes go too far.”

VT SS to the US - July 1998

‘THE young lady was eyeballing the car … “It’s a family car but it’s not like the sort of family cars you usually see. It’s sportier like a [Pontiac] Grand Prix, only better looking. I don’t care much for four-doors but I’d buy one of those.” Maybe there is a market for Holdens in the States.'

The subtext had shifted by the late-’90s, and ‘Wheels Takes on the World Part III.’ The message wasn’t so much ‘we can build a better car than them’ but more precisely, ‘we can design and build a competitive car for them.’

And so Wheels July 1998’s LA to New York epic was born, aboard a one-of-a-kind supercharged VT Commodore SS.

The young waitress knew her cars. “If there’s an American version of the supercharged Commodore SS, Pontiac’s [front-drive] Grand Prix GTP would certainly be it,” wrote long-time Wheels correspondent Bob Hall.

According to the Road & Track in LA, VT’s ride/handling compromise was “quite nice”, with a “tautness that keeps everything under control during spirited driving. Around town and on the freeway, the ride is supple and nicely damped when going over culverts and bumps.”

Yep, Aussie engineers already knew that an absorbent ride and good body and wheel control were not mutually exclusive, though it wasn’t until later that GM discovered and tapped its antipodean talent for the global good.

In New York, praise was delivered with a thick Brooklyn accent. “Hey buddy, what kinda car is that?” “A Holden Commodore.” “Yeah? From Australia? I’ve never seen one. Man it looks really great! They oughta sell it here.”

But in the United States it would nonetheless remain a “forbidden pleasure. Victoria’s Secret, if you will.”

VE Range to Broken Hill - September 2006

It’s impossible to comprehend now, but back when we tackled our VE drive 12 years ago, there were no smartphones and social media was barely in its infancy. As far as we knew, not a single image of our pre-launch VE thrash was uploaded onto the web. Hell, I wasn’t even on Facebook.

With only Thomas Wielecki’s fastidious attention to photographic detail holding up progress, Robbo, Carey and myself flogged a red Commodore Omega, a grey Calais V V6, and a blue SS-V from Lang Lang to Salmon Street, Port Melbourne, via Broken Hill in NSW and Holden’s Elizabeth factory in South Australia. Five big days and 3300 unforgettable kays.

A bunch of highlights remain etched in my memory about that trip. Like hammering into Broken Hill in darkness, myself bringing up the rear in the SS-V at more than 160km/h trying to keep the other VEs’ tail-lights in view. Or the indicated 223km/h we managed to squeeze out of the four-speed-auto Omega on a closed road in outback South Australia. And Thomas and yours truly rocking out to a disco radio station as we neared Adelaide’s outskirts. Stupidly, I’d packed only two CDs (remember those?) – Lenny Kravitz’s ‘Mama Said’ and Franz Ferdinand’s first album – and by day four we were thoroughly jack of both.

Any issues we had with those early VEs – patchy drivetrain refinement, tyre roar from the 19s, and the V8’s lack of burble – were gradually exorcised over the years. But so has the luxury of being able to ‘escape’ from the world. No phone reception, no video crew, no web deadlines. Just us, three unreleased VEs and Australia’s vastness.

COMMENTS